Paper presented to the Land and Environment Court Annual Conference 2011, Sydney

5 May 2011

Every court and tribunal exists in its particular context, that peculiar combination of factors that serves to shape an institution's purpose and operations. The nature of the jurisdiction, the type of people who appear before it, its workload and its resources are but a few of these factors. Practices and procedures develop and evolve within each institution to manage the delivery of justice in its specific setting.

Today, I will talk about the way in which the Administrative Appeals Tribunal has responded to the challenge of delivering justice in its particular context. First, I will outline some of the factors that influence the AAT's approach to dealing with cases. I will then focus on a number of aspects of the review process to illustrate some of the key features of practice and procedure in the AAT, including how the AAT deals with evidence.

KEY CONTEXTUAL FACTORS

Parliamentary direction as to how the AAT should operate

The AAT is not a court. It is a creature of statute and derives its functions and powers solely from legislation. The Administrative Appeals Tribunal Act 1975 (Cth) contains two provisions that give general guidance as to the way in which the AAT is expected to operate. They overlap to some degree. The first section states that, in carrying out its functions, the Tribunal must provide a review process that is fair, just, economical, informal and quick. (1) The second section states that any proceeding is to be conducted with as little formality and technicality, and with as much expedition, as the requirements of the Act and other relevant legislation and a proper consideration of the matters before the Tribunal permit. (2)

These provisions set the broad parameters within which the AAT has developed its practices and procedures. As Gleeson CJ and McHugh J said in Minister for Immigration and Multicultural Affairs v Eshetu, the purpose of these kinds of provisions is “to free tribunals, at least to some degree, from constraints otherwise applicable to courts of law, and regarded as inappropriate to tribunals”. (3) The challenge is to find the appropriate balance between the various elements: fairness, justice, economy, informality and expedition. The way in which the AAT seeks to do this will be another focus of my presentation today.

The AAT's role and jurisdiction

The Tribunal has one primary role: to review on the merits administrative decisions made under Commonwealth laws. To this extent, the AAT's jurisdiction is relatively straightforward. It deals with only one type of dispute.

The AAT does not have a general power to review decisions made under Commonwealth legislation. It can only review a decision if an Act or other legislative instrument confers jurisdiction on the Tribunal. The AAT currently has power to review decisions made under more than 400 Acts or other legislative instruments.

The majority of applications to the AAT relate to decisions in the following areas:

-

social security entitlements

-

taxation

-

veterans' entitlements, and

-

workers' compensation entitlements for Australian Government and ACT Government employees, employees of certain corporations and seafarers.

The AAT also regularly reviews decisions relating to bankruptcy, civil aviation, corporations and financial services regulation, customs, environmental protection, freedom of information, immigration and citizenship, therapeutic goods and industry assistance.

Parliament confers on the AAT the power to review most decisions that will affect a person's interests. Given the wide variety of activities undertaken by the Australian Government, there is considerable diversity in the subject matter of the decisions that come before the AAT. The level of complexity of the factual and legal issues that arise for consideration varies enormously.

Persons involved in reviews at the AAT

There is also quite a degree of diversity in relation to persons who apply to the AAT. The majority of applications are lodged by individuals but they are also lodged by companies, public interest organisations and a range of other entities.

Individual applicants are from all walks of life and are a reflection of contemporary Australia. Applicants come from diverse socio-economic groups and a wide variety of cultural and linguistic backgrounds.

The person or body who made the decision to be reviewed is always a party to the review. This may be a Minister, a government department or agency or a private corporation that has been given authority to make decisions under Commonwealth laws. Other persons whose interests are affected by the decision may also apply to be joined as a party to a review. (4)

Representation is permitted as of right. (5) However, levels of representation vary considerably between the different areas of the AAT's work. The majority of applicants in the veterans' entitlements and workers' compensation areas are represented. In the social security area, most applicants represent themselves.

The type of representation also varies. In many cases, representation will be provided by a lawyer. However, in relation to taxation decisions, applicants may be represented by an accountant. Applicants may also be represented by other non-legal advocates such as migration agents.

This diversity in types of representation extends to decision-makers. They may be represented by external lawyers, in-house lawyers or, in some cases, by specially trained non-legal staff.

For most applicants representing themselves, this will be their first experience in a court or tribunal. They will be wholly unfamiliar with the processes that will be followed. The level of familiarity that representatives have with the AAT and its processes also varies considerably according to their experience.

THE TRIBUNAL'S APPROACH TO PRACTICE AND PROCEDURE

Given the wide variety of decisions that the AAT reviews and the different types of people involved in applications for review, flexibility is the key to the AAT's approach to practice and procedure. The AAT must have flexible processes that facilitate access to, and participation in, the review process and allow each application to be dealt with in the most appropriate manner.

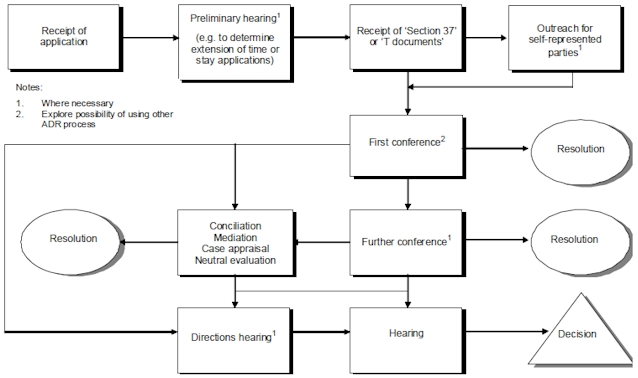

Included in the materials at Attachment A is a flow chart which sets out the way in which most applications are handled. In brief, the AAT's strategy is to use alternative dispute resolution to help the parties try to reach an agreed outcome, where possible, and then to hear and determine the relatively small proportion of cases that cannot be resolved during the pre-hearing process.

The Administrative Appeals Tribunal Act and Regulations set out the Tribunal's powers and some procedural requirements. The AAT does not have any rules but relies on practice directions, jurisdictional guides and guidelines to provide more particular detail in relation to how different types of applications will be managed.

To illustrate the AAT's approach to practice, procedure and evidence, I will talk about four specific aspects of the review process:

- the requirements for making an application

- providing self-represented parties with information about the process

- the use of ADR, and

- the hearing.

I will identify how the AAT seeks to implement its obligation to provide a fair, just, economical, informal and quick review process.

Making an application

The requirements for making an application at the AAT are not onerous. In fact, there are only two key requirements for the application itself: it must be in writing and it must contain a statement of reasons for the application. (6)

A form is available for applicants to use but is not mandatory. Applications are commonly in the form of a simple letter. In relation to the statement of reasons, it is not expected that a detailed outline of the grounds for making the application will be provided. The application is not designed to serve as a form of pleading.

Once the AAT is satisfied it has received a valid application, there is no requirement on the applicant to serve a copy on the decision-maker. The AAT takes on this role and notifies the decision-maker of an application. This triggers the requirement for the decision-maker to send to the AAT and the applicant within 28 days the following documents referred to as the Section 37 documents:

- a statement of reasons for the decision under review, and

- every document in the decision-maker's possession or control that is relevant to the review. (7)

The Administrative Appeals Tribunal Act was drafted to reduce the level of formality and technicality associated with making an application to the AAT. This clearly helps to facilitate access to the tribunal, particularly for those applicants who apply for review without any assistance. The absence of a requirement to set out in the application the grounds for seeking review could be said to disadvantage the decision-maker. However, the scope of the review is explored fully during the pre-hearing process.

Outreach program and legal advice schemes

The AAT is very conscious of the need to assist parties who are representing themselves to participate as fully as possible in the review process. Various steps are taken during the review process to this end. The first steps are taken shortly after an application is lodged.

The letter to an applicant acknowledging receipt of an application sets out basic information in relation to what will happen next in the review. It is accompanied by a plain English brochure relating to the first stage of the review process. Within the next few weeks, an AAT staff member contacts a self-represented party to provide information about the AAT and its processes. This is known as Outreach. Where necessary, an interpreter service is used.

The officer conducting Outreach explains what the s 37 documents are, what will happen next and other procedural matters, such as how to make an application to stay the decision under review. The AAT can arrange to send the person a DVD about the AAT and its procedures. Outreach provides the officer with the opportunity to identify whether the person may need the assistance of an interpreter when dealing with the AAT or whether the person has any particular needs because of a disability. The person is also referred to other organisations that may be able to assist the applicant.

The Tribunal has established legal advice schemes with the cooperation of legal aid bodies in most registries. A legal aid solicitor generally attends the Tribunal once each week or each fortnight. The Tribunal invites self-represented parties to make an appointment to see a solicitor who can provide advice and minor assistance, mostly in social security cases and occasionally in other types of cases. Further assistance, such as representation, may be provided if a person makes a successful application for legal aid.

The Tribunal may also refer self-represented parties to community legal centres and other legal service providers that may be able to provide advice or representation.

These measures are designed to enhance the accessibility of the AAT for people who do not have legal representation.

Conferences and other ADR processes

The AAT has a high rate of success in assisting parties to reach an outcome in their matters without proceeding to a formal hearing. In the 2009-10 financial year, 82 per cent of the approximately 7,500 completed applications were finalised without a decision on the merits following a hearing. The centrepiece of the AAT's pre-hearing process is the conference.

Conferences

In most applications, the parties attend one or more conferences. They can be conducted by AAT members but are generally conducted by an officer known as a Conference Registrar. Conference Registrars must be legally qualified and are ADR specialists. They are not members of the Tribunal, but unlike all other staff, they are appointed personally by the President. The same person will generally conduct all conferences for a particular application.

Where both parties are represented, conferences are generally held by telephone. If an applicant is not legally represented, conferences are held in person at the AAT's premises unless this would not be convenient for one of the parties because of geographic or other reasons.

Conferences provide an opportunity for the AAT to work with the parties to:

- define the issues in dispute

- identify any further supporting material the parties may wish to obtain, including witness statements, expert reports or other documents; and

- explore whether the matter can be settled.

Conference Convenors may offer frank advice in relation to the adequacy of the evidence or the prospects of success in an application.

At the first conference, the Conference Convenor will usually set a timetable for the parties to lodge further material and for the holding of another conference. Later conferences provide an opportunity for the AAT and the parties to review the further material and explore the possibility of settlement. Represented parties may be required at that stage to lodge and exchange a Statement of Facts, Issues and Contentions outlining their case, to assist in this process.

Conferences also provide the opportunity for the AAT to discuss with the parties the future conduct of the application and, in particular, whether another form of ADR may assist in resolving the matter. Where the Conference Convenor is satisfied that an application is unlikely to settle, arrangements for preparing the matter for hearing are discussed with the parties. The Conference Convenor will issue directions as necessary to ensure that any further material is lodged in a timely manner. In general, parties are required to lodge and exchange all evidence on which they intend to rely well before the hearing.

The conference process works well at the AAT because of its flexibility and informality. It is a process that applies whatever is the complexity of the issues raised by the decision under review and whether or not the parties are represented. Conferences provide an opportunity to focus the parties on what is at issue and seek to resolve the application in an effective and efficient manner.

Conferencing is particularly effective when an applicant is self-represented. In addition to ensuring the applicant understands the process, Conference Convenors are able to discuss substantive issues arising in the review. In the first instance, they will seek to ensure the applicant understands why the decision was made and the legal framework within which it was made.

Conference Convenors can also identify the kind of evidence the applicant needs to support his or her case and discuss how that material could be gathered. This may include requesting the decision-maker to obtain further evidence. In some cases, the AAT may itself issue a summons for the production of relevant documents. This approach is consistent with the AAT's role as an administrative decision-maker that must make the correct or preferable decision on review. The AAT will seek to ensure that, as far as possible, relevant material is available to consider. Providing self-represented applicants with assistance that helps them to understand and present their case also contributes to the fairness and justice of the review process.

Other ADR processes

In addition to conferencing, the Administrative Appeals Tribunal Act provides for conciliation, mediation, case appraisal and neutral evaluation. (8) The AAT has undertaken considerable work to clarify how these different forms of ADR are to operate. They encompass both advisory, facilitative and hybrid dispute resolution processes.

The AAT has developed process models for each form of ADR. Each process model sets out a definition of the process and then provides a range of information relating to the conduct of the process including:

- the stage of the proceedings at which the process is likely to be undertaken;

- a description of the way in which the process will proceed;

- the role of the person conducting the process as well as the role of the parties and their representatives; and

- what is likely to occur at the conclusion of the process.

The AAT has also developed a set of guidelines designed to assist Conference Registrars and AAT members to determine when it may be appropriate to refer an application to a particular type of ADR process. The guidelines set out a range of considerations to be taken into account, including such things as:

- the capacity of the parties to participate and their attitudes;

- the nature of the issues in dispute;

- the likelihood of reaching agreement or reducing the issues in dispute; and

- the cost to the parties.

The guidelines identify factors that may make a particular form of ADR suitable for use. For example, mediation may be suitable where flexible options need to be explored or there will be an ongoing relationship between the parties.

The type of ADR process most commonly used in the AAT after conferencing is conciliation. It is usually held in a workers' compensation application that has not resolved during the conference process if both parties are represented, but is also used in other jurisdictions. Mediation, case appraisal and neutral evaluation are used in a range of matters.

General matters applying to ADR in the AAT

ADR processes may be conducted by an AAT member, a Conference Registrar or another person engaged by the AAT. (9) Case appraisals and neutral evaluations are generally conducted by members. The Act does not contain a blanket prohibition on a member who has conducted an ADR process from proceeding to hear the matter but, in practice, this does not occur. Parties have the right to object to that member participating in the hearing. (10)

ADR processes are conducted in private. In general, evidence of anything said or done during an ADR process is not admissible in a hearing without the consent of the parties. (11) Parties are required to act in good faith. (12)

The AAT's use of ADR is a key way in which it seeks to make the review process economical, quick and informal. While the primary goal may be to attempt to reach an agreed outcome, ADR can also help to clarify and narrow the issues in dispute between the parties. The use of ADR can reduce the costs incurred by the parties and the Tribunal by reducing the length of a hearing or avoiding the need for a hearing altogether. ADR processes lead to applications being finalised earlier than would otherwise have been the case and are a means of reaching an outcome that parties will prefer. In particular, they provide a forum in which the issues can be explored and discussed in detail that is less daunting for many parties than a formal hearing.

Hearings

If an application is not finalised during the pre-hearing process, the AAT will conduct a hearing. The AAT can dispense with the hearing and determine the application on the papers if all parties agree and the AAT is satisfied this is appropriate, but this occurs only rarely. (13)

The AAT's hearings are generally conducted in public. (14) However, the AAT has a broad power in appropriate circumstances to make orders protecting the identity of parties and witnesses as well as restricting or prohibiting the disclosure of oral evidence or documents given to the AAT.

Constituting the AAT for hearing

For the purposes of a hearing, the AAT may be constituted by one, two or three members. (15) In rare cases, the legislation conferring jurisdiction on the AAT determines that the AAT must be constituted in a particular way. In practice, most hearings are conducted by single-member tribunals.

How the AAT will be constituted for a particular application relates primarily to the legal and factual issues to be determined. The AAT Act sets out a list of factors that must be taken into account. These include the degree to which it would be desirable for the AAT to be constituted by members with knowledge, expertise or experience in relation to the matter to be determined. (16)

One of the AAT's particular strengths is that its membership includes persons with expertise in a wide range of areas relevant to the AAT's jurisdiction. Current members have expertise in aviation, engineering, environmental science, medicine, pharmacology, military affairs and public administration. Of course, many of the AAT's members are also experienced lawyers. The ability to draw on this range of expertise when reviewing decisions contributes significantly to the quality of its decisions. It is also valuable for ADR processes where the issues in dispute are specialised in nature.

Conducting the hearing

Hearings at the AAT generally follow the basic structure used in court proceedings. Each party is given an opportunity to present evidence and to make submissions after the evidence has been presented. However, the way in which a particular hearing proceeds will vary according to the nature of the decision under review and the parties involved in the hearing.

To illustrate the point, a hearing with a self-represented applicant concerning the review of a social security decision will be quite different from a hearing relating to the tax liability of a large company where all parties have high-level legal representation. The AAT adapts its procedures to ensure the hearing proceeds in the most effective manner possible and all relevant evidence is elicited.

Hearings involving self-represented parties are generally conducted in a smaller, more informal hearing room. The presiding member will also usually modify the hearing procedure in various ways to assist the person to present their case. He or she will explain at the outset what will happen at the hearing and either outline the nature of the case and the issues to be decided or ask the decision-maker's representative to do so. The applicant will often not be required to give evidence from the witness box and the presiding member will take responsibility for asking questions of the applicant and any witnesses. The order in which evidence is given and submissions are made may also be changed.

Even in hearings involving represented parties, there are certain ways in which the approach taken by the AAT differs from the courts. The first of these relates to the admissibility of evidence.

As is the case for many tribunals, the AAT is not bound by the rules of evidence and may inform itself on any matter as it thinks appropriate, subject to the requirements of procedural fairness. (17) While this does not mean the AAT cannot apply the rules of evidence, the AAT does not generally do so. As Justice Hill stated in Casey v Repatriation Commission:

The criterion for admissibility of material in the tribunal is not to be found within the interstices of the rules of evidence but within the limits of relevance. (18)

Material relevant to the matters to be determined will generally be admitted avoiding the need for technical arguments on what should or should not be admitted during the course of the hearing. The issue then becomes what weight should be attached to the material. In this regard, the principles underlying the rules of evidence may well be of assistance in considering this issue.

A second area of difference relates to the modes of participation in hearings. While the majority of hearings are conducted in person, parties and witnesses can participate by telephone or by video at the AAT's discretion. (19) Taking evidence by telephone occurs quite frequently in the AAT. In some registries, this has become the usual way in which experts give evidence.

Another area in which the AAT differs from many courts, although not the Land and Environment Court, is its willingness to hear the evidence of experts concurrently. Before I talk about this, I should make some general remarks about the AAT's approach to expert evidence.

A broad range of expert evidence can be relevant to applications in the AAT. By far the most common form is expert medical evidence which is relied on principally in veterans' entitlements cases, workers' compensation applications and certain types of social security matters. While the AAT may explore with the parties whether a joint report would be suitable in a particular case, the norm is for parties to seek their own expert report if they consider this necessary.

This practice accords with my own view that, in areas where experts may genuinely hold different views, a decision-maker will usually be better able to decide a case if presented with these different perspectives. Use of single experts can narrow the scope of what is put before a decision-maker to consider.

The AAT has used concurrent evidence procedures over many years. In 2005, it published the results of a study into its use in the Sydney Registry. The study confirmed the benefits of the procedure for decision-makers. Dealing with all of the evidence on a topic at the same time allows areas of agreement and disagreement and the reasons for any disagreement to be identified clearly. AAT members reported that the quality and objectivity of the evidence given improved and that the procedure enhanced the decision-making process.

In relation to the impact of the procedure on the length and cost of hearings, the Tribunal's experience is that, in cases where the parties seek to call a large number of expert witnesses to give evidence, the concurrent evidence procedure can save significant amounts of hearing time. While the potential for significant time savings is more limited in the AAT's typical cases involving a small number of experts, the study indicated that the procedure offers a number of clear benefits without impacting adversely on hearing length in most cases.

Use of concurrent evidence procedures is one of the options available to the AAT at hearing to ensure it elicits evidence that will assist the AAT to reach the correct or preferable decision.

CONCLUSION

The AAT has developed a set of practices and procedures designed to deliver justice in its context. It aims to provide fair and just review of a broad range of administrative decisions in a flexible and appropriate way for the diverse members of the Australian community. As Deputy President Todd noted in 1985:

... the Tribunal has been given a degree of flexibility to deal with proceedings before it as it sees fit. The experience of the Tribunal has been that, ..., there is no one level of formality or informality which is appropriate for all cases. (20)

The AAT employs a set of rigorous methods that can be tailored in each case to facilitate the participation of all of the parties in the review process and ensure that applications move towards resolution in an effective and efficient manner. The AAT's extensive use of ADR and the fact that the majority of cases do not proceed to a formal hearing reflect a commitment to providing a process that is economical, informal and quick, while continuing to be fair and just. Hearings, when they occur, are conducted in a setting which is as informal as possible and focussed on ensuring the AAT has a sound basis on which to make the correct or preferable decision.

ATTACHMENT A

Administrative Appeals Tribunal: Dispute Resolution Flow Chart

Footnotes

-

Section 2A of the Administrative Appeals Tribunal Act 1975 (Cth).

-

Section 33(1)(b) of the Administrative Appeals Tribunal Act.

-

(1999) 197 CLR 611 at [49].

-

Section 30 of the Administrative Appeals Tribunal Act.

-

Section 32 of the Administrative Appeals Tribunal Act.

-

Section 29(1) of the Administrative Appeals Tribunal Act. The application must also be lodged within the prescribed time limit and an application fee is payable for certain types of applications.

-

Sections 37(1) and (1AE) of the Administrative Appeals Tribunal Act.

-

Section 3(1) of the Administrative Appeals Tribunal Act.

-

Section 34C(5) of the Administrative Appeals Tribunal Act.

-

Section 34F of the Administrative Appeals Tribunal Act.

-

Sections 34E(1) and (2) of the Administrative Appeals Tribunal Act. The Act recognises that it may be appropriate for the report of a case appraisal or neutral evaluation to be admitted at a hearing. This may occur unless one of the parties objects to the report being admitted: s 34E(3).

-

Sections 34A(5) and 34B(4) of the Administrative Appeals Tribunal Act.

-

Section 34J of the Administrative Appeals Tribunal Act.

-

Section 35 of the Administrative Appeals Tribunal Act.

-

Section 21(1) of the Administrative Appeals Tribunal Act.

-

Section 23B of the Administrative Appeals Tribunal Act.

-

Section 33(1)(c) of the Administrative Appeals Tribunal Act.

-

(1995) 39 ALD 34 at 38.

-

Section 35A of the Administrative Appeals Tribunal Act.

-

Re Hennessy and Secretary to Department of Social Security (1985) 7 ALN N113 at N117.