Part 3 – Performance report

Contents

- Performance framework

- Financial performance

- Overview of caseload

- Conduct of reviews

- Interpreters

- Outcomes of review

- Timeliness

- Judicial review

- Social justice and equity

- Complaints

- Migration agents

- Community and interagency liaison

- Major reviews

- Significant changes in the nature of functions or services

- Developments since the end of the year

- Case studies – Matters before the tribunals

The tribunals contributed to Australia’s migration and refugee programs during the year through the provision of quality and timely reviews of decisions.

Performance framework

The tribunals operate in a high volume decision making environment where the case law and legislation are complex and technical. The tribunals have identical statutory objectives, set out in sections 353 and 420 of the Migration Act:

The tribunal shall, in carrying out its functions under this Act, pursue the objective of providing a mechanism of review that is fair, just, economical, informal and quick.

The key strategic priorities are to meet these statutory objectives through the delivery of consistent, high quality reviews, and timely and lawful decisions.

Each review must be conducted in a way that ensures, as far as practicable, that the applicant understands the issues and has a fair opportunity to comment on or respond to any matters which might lead to an adverse outcome.

The tribunals also aim to meet government and community expectations and to have effective working relationships with stakeholders. These priorities are reflected in the tribunals’ plan.

For 2012-13, one outcome was specified in the Portfolio Budget Statement:

To provide correct and preferable decisions for visa applicants and sponsors through independent, fair, just, economical, informal and quick merits reviews of migration and refugee decisions.

The tribunals had one program contributing to this outcome, which was:

Final independent merits review of decisions concerning refugee status and the refusal or cancellation of migration and refugee visas.

Table 3 summarises performance against the program deliverables and key performance indicators that were set out in the Portfolio Budget Statement.

| Measure | Result |

|---|---|

| Deliverables | |

| 9,065 decisions | 19,347 decisions |

| Key performance indicators | |

| Less than 5% of tribunal decisions set-aside by judicial review |

0.1% of MRT and 0.7% of RRT decisions made in 2012-13 were set-aside by judicial review |

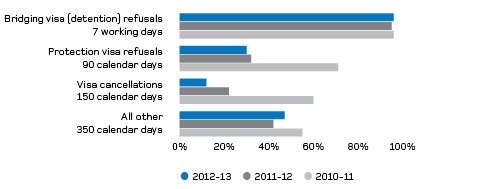

| 70% of cases decided within time standards | 96% of bridging visa (detention) refusals were decided within seven working days 30% of protection visa refusals were decided within 90 calendar days 12% of visa cancellations were decided within 150 calendar days 47% of all other visa refusals were decided within 350 days |

| Less than five complaints per 1,000 cases decided | The tribunals received less than two complaints per 1,000 cases decided (33 complaints in total) |

| 40% of decisions published | The tribunals published 24% of all decisions made in 2012-13 (4,783 decisions in total) |

The timeliness of reviews has been affected by large increases in lodgements and cases on hand over the past few years, however, this began to improve at the end of 2012-13. This was a very pleasing result given that lodgements increased by 18% over the year.

The tribunals did not meet the target of publishing 40% of decisions, however, the number of decisions published compares with 4,546 in 2011-12 and 3,909 in 2010-11. In view of the much higher volume of decisions being made, the key performance indicator for decision publication has been revised for 2013-14 to at least 4,500. This will continue to ensure that a wide range of decisions are published.

A challenge in 2012-13 was balancing priorities across the different caseloads, which have grown significantly from previous years. The tribunals received 20,393 lodgements in 2012-13, an increase of 18% compared with 2011-12. In addition, 18,364 cases were carried over from 2011-12.

Financial performance

The MRT and the RRT are prescribed as a single agency, the ‘Migration Review Tribunal and Refugee Review Tribunal’ for the purposes of the FMA Act. The tribunals are funded based on a model which takes into account the number of cases decided. The tribunals’ base funding in 2012–13 covered deciding 9,065 cases, with the model providing for additional appropriation at a marginal cost per case rate. The tribunals decided 19,347 cases in 2012-13 and the revenue as set out below takes into account an adjustment to appropriation based on the actual number of cases decided.

Revenues from ordinary activities totalled $97.03 million and expenditure totalled $72.50 million, including depreciation worth $2.47 million, resulting in a net surplus for 2012-13 of $24.53 million. Included in revenue is $28.3 million transferred from the Department of Immigration and Citizenship as part of the Machinery of Government (MoG) transfer from the Department on 1 July 2012 of the remaining operations and staff of the Independent Protection Assessment Office (IPAO). This was a one-off transfer of appropriation as there was no funding for the IPAO beyond 2012-13, and ongoing staff costs are being managed within the MRT-RRT funding.

During the year, the tribunals funding model was reviewed which will see an increase in base funding for 2013–14 onwards from 9,065 to 18,000 cases to reflect the increase in lodgements over several years.

The tribunals administer application fees on behalf of the government. Details of administered revenue are set out in the financial statements. The financial statements for 2012–13, which are set out in part 5, have been audited by the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) and received an unqualified audit opinion.

Overview of caseload

MRT and RRT caseload

The tribunals received 20,393 lodgements during the year, decided 19,347 cases and had 19,410 cases on hand at the end of the year. Table 4 provides an overview of the tribunals’ caseload over the past three years.

| 2012-13 | 2011-12 | 2010-11 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MRT | |||

| On hand at start of year | 16,863 | 10,786 | 7,048 |

| Lodged | 16,164 | 14,088 | 10,315 |

| Decided | 15,590 | 8,011 | 6,577 |

| On hand at end of year | 17,437 | 16,863 | 10,786 |

| RRT | |||

| On hand at start of year | 1,501 | 1,100 | 738 |

| Lodged | 4,229 | 3,205 | 2,966 |

| Decided | 3,757 | 2,804 | 2,604 |

| On hand at end of year | 1,973 | 1,501 | 1,100 |

| TOTAL MRT AND RRT | |||

| On hand at start of year | 18,364 | 11,886 | 7,786 |

| Lodged | 20,393 | 17,293 | 13,281 |

| Decided | 19,347 | 10,815 | 9,181 |

| On hand at end of year | 19,410 | 18,364 | 11,886 |

Additional statistical information regarding the MRT and RRT caseloads is provided in appendix A.

Independent Protection Assessment Office caseload

In addition to deciding tribunal reviews, the tribunals also took over administration of the remaining operations of the Independent Protection Assessment Office (IPAO) from 1 July 2012. This involved deciding 702 cases, with a recommendation favourable to the asylum seeker made in 68% of cases.

Over the life of the IPAO from 2008 to 2012, a total of 5,217 cases were completed by persons engaged as reviewers. Of these cases, a recommendation favourable to the asylum seeker was made in 74% of cases.

At the time of transfer of functions from the department on

1 July 2012, there were 87 active reviewers. All reviewer appointments expired on or before 31 December 2012.

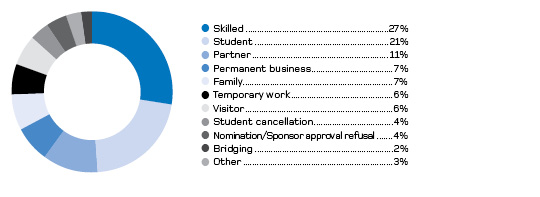

Lodgements

The MRT has jurisdiction to review a wide range of visa, sponsorship and other decisions for migration and temporary entry visas. In 2012-13, the MRT received 16,164 lodgements which included significant increases in temporary work, family, permanent business and partner lodgements. Figure 1 provides an overview of MRT lodgements by case category.

Figure 1 – MRT lodgements by case category

The MRT’s jurisdiction to review decisions about visas applied for outside Australia depends on whether there is a requirement for an Australian sponsor or for a close relative to be identified in the application. These cases are mainly in the permanent business, visitor, partner and family categories. In 2012-13, approximately 20% of visa refusal applications to the MRT were for persons outside Australia seeking a visa.

The RRT has jurisdiction to review decisions to refuse protection visas. In 2012-13 more than 5,000 protection visa applications were refused by a delegate of the Minister.

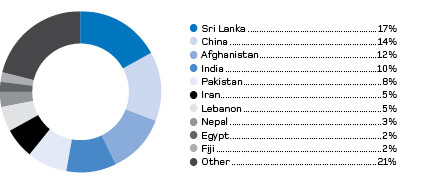

Nationals of five countries - Sri Lanka, China, Afghanistan, India and Pakistan – comprised 61% of all RRT lodgements

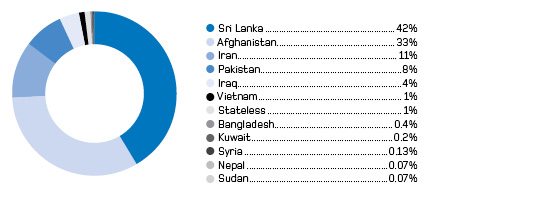

The RRT received 4,229 lodgements in 2012-13, which included 1,518 from unauthorised maritime arrivals. Lodgements related to persons from 107 countries. Nationals of five countries – Sri Lanka, China, Afghanistan, India and Pakistan – comprised 61% of all lodgements. The largest number of applications was from nationals of Sri Lanka, which made up 17% of the applications lodged. This is the first time since 2003-04 that China was not the country with the highest number of applications lodged and reflects the impact of lodgements from unauthorised maritime arrivals on the composition of the caseload.

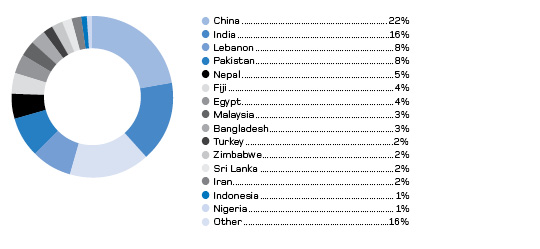

Figures 2, 3 and 4 provide an overview of RRT lodgements by the applicant’s country of origin. Figure 2 includes all lodgements received by the RRT, while figure 3 displays the countries of unauthorised maritime arrivals only. Figure 4 displays the countries of all other RRT applicants (excluding unauthorised maritime arrivals).

Figure 2 – RRT lodgements by country

Figure 3 – RRT lodgements by country for unauthorised maritime arrivals

Figure 4 – RRT lodgements by country for applicants other than unauthorised maritime arrivals

Applicants to the tribunals tend to be located in the larger metropolitan areas. Thirty-seven per cent of all applicants resided in New South Wales, mostly in the Sydney region. Approximately 33% of applicants resided in Victoria, 12% in Queensland, 10% in Western Australia, 5% in South Australia, 1% each in the Australian Capital Territory and in the Northern Territory, and less than 1% in Tasmania. Over the past five years, the proportion of lodgements from New South Wales has decreased significantly – from 52% in 2007-08 to 37% in 2012-13. While much of the decrease in the proportion of lodgements in New Sout Wales has been taken up by Victoria, increases in the proportion of lodgements over the past five years have also occurred in Queensland, Western Australia and South Australia.

Cases involving applicants in immigration detention comprised 3.5% of the cases lodged.

Conduct of reviews

The proceedings of the tribunals are inquisitorial and do not take the form of litigation between parties. The review is an inquiry in which the member identifies the issues or criteria in dispute, initiates investigations or inquiries to supplement evidence provided by the applicant and the department and ensures procedural momentum. At the same time, the member must maintain an open and impartial mind.

In 2012-13, 11,281 MRT and 5,296 RRT hearings were arranged. Of these, 6,834 MRT and 3,675 RRT hearings were completed or adjourned. The remaining hearings were postponed or rescheduled or did not proceed as the applicant did not attend.

Cases where no hearing is arranged include those where a decision favourable to the applicant is made or the applicant withdraws prior to a hearing being arranged. Favourable decisions were made in 6% of MRT cases and in 2% of RRT cases without the need for a hearing.

Video links were used in 17% of MRT hearings and telephone in 2% of hearings. The average duration of MRT hearings was 63 minutes and the average duration of RRT hearings was 141 minutes. Two or more hearings were held in 11% of RRT cases and in 2% of MRT cases.

Interpreters

High quality interpreting services are fundamental to the work of the tribunals. In 2012-13, interpreters were required for 56% of MRT hearings and 89% of RRT hearings. Interpreters were required in approximately 94 languages and dialects, up from 84 the previous year.

The tribunals’ Interpreter Advisory Group (IAG), a national committee comprising members and staff, works to uphold best-practice interpreting at hearings.

Outcomes of reviews

Interpreters in 94 languages and dialects were used in tribunal hearings

A written statement of decision and reasons is prepared in each case and provided to both the applicant and the department.

The MRT set-aside, or set-aside and remitted, the primary decision in 29% of cases decided and affirmed the primary decision in 46% of cases decided. The remaining cases were either withdrawn by the applicant or were cases where the tribunal decided it had no jurisdiction to conduct the review. The set-aside rate in 2012-13 was significantly lower than the rate of 37% in 2011-12. One contributing factor was a lower set-aside rate for student and skilled refusals, which together comprised 53% of decisions made.

37% of RRT and 29% of MRT cases were decided in favour of the applicant

The RRT remitted the primary decision in 37% of cases decided and affirmed the primary decision in 59% of cases decided. The remaining cases were either withdrawn by the applicant or were cases where the tribunal decided it had no jurisdiction to conduct the review. The RRT remit rate was significantly higher than the rate of 27% in 2011-12. This is directly related to the unauthorised maritime arrival caseload for which the set-aside rate was 65%. Most unauthorised maritime arrivals came from countries where there are generally high rates of acceptance of claims at both the primary and review level.

Most RRT remittals were on the basis that the applicant was a refugee. There were also 63 cases remitted with a direction that the applicant met the complementary protection criterion.

The fact that a decision is set-aside by the tribunal is not necessarily a reflection on the quality of the primary decision, which may have been correct and reasonable based on the information available at the time of the decision.

Applications for review typically address the issues identified by the primary decision maker by providing submissions and further evidence to the tribunal. By the time of the tribunal’s decision, there is often considerable additional information before the tribunal. There may also be court judgments or legislative changes which affect the outcome of the review. Applicants were represented in 64% of cases decided. Most commonly, representation was by a registered migration agent. In cases where applicants were represented, the set-aside rate was higher than for unrepresented applicants. The difference was more notable for RRT cases, where the set-aside rate was 47% for represented applicants and 11% for unrepresented applicants. All unauthorised maritime arrival applicants have been offered representation at primary and review stages through the government-funded Immigration Advice and Application Assistance Scheme (IAAAS) and this caseload has a higher set-aside rate than other caseloads. Unrepresented applicants may not have sought advice on their prospects of success before applying for review or may have applied despite obtaining advice that the prospects of success were low. Only 66% of unrepresented applicants to the RRT attend hearings, compared to almost 87% of represented applicants. For the MRT, there was also a significant difference in outcome for unrepresented applicants. The set-aside rate was 33% for represented applicants and 22% for unrepresented applicants.

A total of 314 cases (approximately 2% of the cases decided) were referred to the department for consideration under the Minister’s intervention guidelines. These cases raised humanitarian or compassionate circumstances which members considered should be drawn to the attention of the Minister.

Timeliness

Cases are allocated to members in accordance with legislation and directions regarding the order in which cases are to be dealt with. Depending on available member capacity and lodgements, this may mean that not all cases can be quickly allocated to a member. Following allocation of a case, members are expected to promptly identify the relevant issues and the course of action necessary to enable the review to be conducted as effectively and efficiently as possible. Senior members manage their teams’ caseloads to achieve tribunal decision and timeliness targets, including by monitoring older and priority cases to minimise unnecessary delays, and managing member performance. Figure 5 displays the percentage of cases decided within the tribunals’ time standards over the past three years.

Figure 5 – Percentage of cases decided within time standards

Some cases cannot be decided within the time standards. These include cases where hearings need to be rescheduled because of illness or because an interpreter is not available, cases where the applicant requests further time to comment or respond to information, cases where new information becomes available, and cases where information or an assessment needs to be obtained from another body or agency. In the early months of processing unauthorised maritime arrival cases, there were additional difficulties associated with arranging hearings for applicants in immigration detention or without a stable residential address and contact information.

The timeliness of reviews has been affected by large increases in lodgements and cases on hand over the past few years, however, this began to improve at the end of 2012-13. This was a very pleasing result given that lodgements increased by 18% over the year.

The Principal Member reports every four months on the RRT’s compliance with the 90 day standard for RRT reviews. These reports are provided to the Minister for tabling in Parliament. In 2012-13, only 30% of RRT cases were decided within 90 days; the average time to decision was 159 days.

In 2013-14, the tribunals will continue to focus on increasing productivity through member specialisation, the use of hearing lists for less complex cases, changes in decision writing and other measures designed to enhance efficiency.

Judicial review

For persons wishing to challenge a tribunal decision, two avenues of judicial review are available. One is to the Federal Circuit Court, formerly the Federal Magistrates Court, and the other is to the High Court. Decision making under the Migration Act remains an area where the level of court scrutiny is very intense and where the same tribunal decision or the same legal point may be upheld or overturned at successive levels of appeal.

The applicant and the Minister are generally the parties to a judicial review of a tribunal decision. Although joined as a party to proceedings, the tribunals do not take an active role in litigation. As a matter of course, the tribunals enter a submitting appearance, consistent with the principle that an administrative tribunal should generally not be an active party in judicial proceedings challenging its decisions.

In 2012-13 the number of tribunal decisions taken to judicial review increased significantly in comparison with previous years, reflecting the larger number of decisions made by the tribunals during 2012-13. However the percentage of decisions taken to judicial review, while fluctuating over recent years, remains

broadly consistent.

Less than 1% of tribunal decisions made in 2012-13 have been set-aside or quashed by the courts

Of all decisions made by the tribunals in 2012-13, only a small percentage (0.1% of MRT decisions and 0.7% of RRT decisions) have been set-aside or quashed by the courts. If a tribunal decision is set-aside or quashed, the court order is usually for the matter to be remitted to the tribunal to be reconsidered. In such cases, the tribunal (which may be constituted by the same or a different member) must reconsider the case and make a fresh decision, taking into account the decision of the court and any further evidence or changed circumstances. In 43% of MRT cases and 29% of RRT cases reconsidered in 2012-13, the reconstituted tribunal made a decision favourable to the applicant.

Table 5 sets out judicial review applications and outcomes for the tribunal decisions made over the last three years. It displays the number of tribunal decisions made during the reporting period that have been the subject of a judicial review application, and the judicial review outcome for those cases.

| MRT | RRT | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012-13 | 2011-12 | 2010-11 | 2012-13 | 2011-12 | 2010-11 | |

| Tribunal decisions | 15,590 | 8,011 | 6,577 | 3,757 | 2,804 | 2,604 |

| Court applications | 653 | 261 | 255 | 743 | 698 | 541 |

| % of tribunals decisions | 4.2% | 3.3% | 3.9% | 19.8% | 24.9% | 20.8% |

| Applications resolved | 196 | 242 | 252 | 201 | 618 | 537 |

| – decision upheld or otherwise resolved | 174 | 205 | 219 | 176 | 545 | 497 |

| – set-aside by consent or judgement | 22 | 37 | 33 | 25 | 73 | 40 |

| – set-aside decisions as % of judicial applications resolved | 11.2% | 15.3% | 13.1% | 12.4% | 11.8% | 7.4% |

| – set-aside decisions as % of total tribunal decisions made | 0.1% | 0.5% | 0.5% | 0.7% | 2.6% | 1.5% |

The outcome of judicial review applications is reported on completion of all court appeals against a tribunal decision. Previous years’ figures are affected if a further court appeal is made against a case that was previously counted as completed.

Notable judicial decisions

Summaries of some notable judicial decisions since 1 July 2012 are set out on the following pages. These decisions had an impact on the tribunals’ decision making or procedures, or on the operation of judicial review regarding tribunal decisions.

As there are restrictions on identifying applicants for protection visas, letter codes or reference numbers are used by the courts in these cases. Unless stated otherwise, references are to the Migration Act and Migration Regulations. The Minister is a party in most cases, and ‘MIAC’ is used to identify the Minister in the abbreviated citations provided.

Completion of review function

The RRT affirmed the decision of a delegate of the Minister not to grant the visa applicant a protection visa. The RRT completed the decision at 2:32 pm on 27 July 2011 and, in accordance with its internal processes, alerted the registry that the decision was ready for release to the applicant and the department. At 4:57 pm, the applicant’s adviser faxed further submissions. Between 4:57 pm and 6:34 pm, when the decision was notified to the applicant’s advisers by fax, the submissions were considered and the presiding member decided that there was no jurisdictional error and the case could not be reopened. On appeal, the Full Federal Court held the tribunal was not functus officio, that is, it had not completed its function, until the decision was ‘beyond recall’. The court said that there was no support in the evidence or in any of the statutory provisions to suggest that it was beyond the power of the member to recall the decision prior to its dispatch. It held that the RRT erred in concluding that it was prevented from considering further material unless it was established there had been a jurisdictional error in making the decision. [MIAC v SZQOY [2012] FCAFC 131].

Notification of decision

The RRT affirmed a decision not to grant the visa applicant a protection visa before the complementary protection provisions came into effect on 24 March 2012 and sent a copy of its decision to the applicant at his former address in Sydney, as well as to the department. The Sydney address was not the applicant’s last residential address provided to the RRT in connection with the review and the RRT did not send a copy of its decision to the correct address until after the complementary protection provisions had come into effect. The Federal Circuit Court held that the RRT had not notified the applicant in accordance with the notification provisions before 24 March 2012. Therefore, the application for review had not been ‘finally determined’ at that

date, and the RRT fell into jurisdictional error by failing to consider the complementary protection grounds. [SZRNY v MIAC [2013] FCCA 197].

Complementary protection and standard of state protection

The Minister appealed from an RRT decision finding that there were substantial grounds for believing that, as a necessary and foreseeable consequence of the applicant being removed from Australia to a receiving country, there was a real risk that he would suffer significant harm. In finding that there was a real risk that the visa applicant would suffer significant harm in the receiving country, the RRT found that the visa applicant could not obtain from an authority in the receiving country protection such that there would not be a real risk that he would suffer significant harm if he was returned there. The RRT found that section 36(2B)(b) of the Act required a standard of protection different from the concept of state protection under the Refugees Convention. The Full Federal Court held that this was correct. It held that the section requires an assessment of whether the level of protection offered by the receiving country reduces the risk of significant harm to the non-citizen to something less than a real one. [MIAC v MZYYL [2012] FCAFC 147]

Complementary protection and significant harm

The applicant applied for a protection visa after the cancellation of his Subclass 444 (Special Category) visa, which he had held for over 15 years. He claimed that he wanted to remain in Australia to be with his five children, that he feared harm from his father and from gangs in New Zealand and that he would be unable to find a job or accommodation in New Zealand. In affirming the delegate’s refusal decision, the RRT made a number of findings dealing with the risk of violence from the applicant’s father and from gangs, and about his capacity to obtain accommodation and employment in New Zealand. Before the court the applicant claimed that the RRT had failed to give meaningful consideration to whether the separation of the applicant from his children might constitute degrading treatment. The Federal Magistrates Court held that the act of removal resulting in forced separation from children residing in Australia, or the ongoing effect of that separation in New Zealand, did not constitute significant harm, and in particular degrading treatment. It said that any harm stemming from the applicant’s separation from his children in Australia stemmed from his removal from Australia, not his presence in any other country, and the relevant act in the definition of degrading treatment cannot be the act of removal itself. [SZRSN v MIAC [2013] FMCA 78].

Reasonableness of refusal of request for adjournment

The applicant was an overseas student seeking to gain residency through a skilled visa. The visa was not granted on the basis that she had provided false information in support of a skills assessment as a cook by Trades Recognition Australia. The applicant had obtained a second but unfavourable skills assessment by the time of the MRT hearing, and was in the process of seeking a review of that assessment from Trades Recognition Australia. The applicant requested the MRT to

adjourn the review pending the outcome of that consideration. The MRT did not agree to this and made a decision noting only that the applicant had been provided with enough opportunities to present her case and it was not prepared to delay any further. On appeal from the Full Federal Court, the High Court held that the MRT had not given adequate consideration to the request for adjournment, such requests needing to be considered reasonably. [MIAC v Li [2013] HCA 18].

Skills assessment and relevant assessing authority

The applicant was an overseas student seeking to gain residency through a skilled visa. The applicant had obtained a skills assessment as a cook by Trades Recognition Australia but this assessment had subsequently been revoked on the basis of concerns about the evidence provided about work experience. Before the MRT there was the question of whether the applicant would seek another skills assessment. However, the applicant argued that Trades Recognition Australia had not been correctly authorised at the time of its assessment. The MRT determined that Trades Recognition Australia was authorised at the time of the MRT’s decision, and affirmed the primary decision on the basis that the applicant did not at time of decision have a skills assessment by the relevant assessing authority. The Federal Magistrates Court upheld the MRT’s decision, finding that Trades Recognition Australia was validly specified at the time of the MRT’s decision as the relevant assessing authority. The court held that the Minister’s authorisation did not purport to take effect before the date it was registered; however, it nonetheless applied to future decisions for visa applications that had been made before that date. [Zhang v MIAC [2012] FMCA 1011].

Social justice and equity

The tribunals’ service charter expresses the commitment to providing a professional and courteous service to applicants and when dealing with other persons. It sets out general standards for client service covering day-to-day contact with the tribunals, responding to correspondence, arrangements for attending hearings, the use of interpreters and the use of clear language in decisions. The service charter is available in Arabic, Bengali, Chinese, English, Hindi, Korean, Nepali, Punjabi, Tamil, Turkish and Vietnamese.

In July and August 2012 the tribunals engaged Buchan Consulting to survey applicants, interpreters and migration agents. The survey allowed the tribunals to gauge perceptions of its performance across a range of criteria and assist future strategic planning. The survey obtained the views of 340 applicants whose cases had been decided, 232 migration agents and 389 interpreters. The results of the survey were positive. High levels of service from staff and members, and positive reports about the overall review process were areas where the tribunals are performing well across all surveyed groups.

Table 6 sets out the tribunals’ performance during the year against service standards contained in the service charter.

| Service standard | Report against standard for 2012-13 | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Be helpful, prompt and respectful when we deal with you | All new members and staff attended induction training emphasising the importance of providing quality service to clients. | Achieved |

| 2. Use language that is clear and easily understood | Clear English is used in correspondence and forms. Staff use professional interpreters to communicate with clients from non-English speaking backgrounds. There is a language register listing staff available to speak to applicants in their language, where appropriate. | Achieved |

| 3. Listen carefully to what you say to us | The tribunals book interpreters for hearings whenever they are requested by applicants and wherever possible accredited interpreters are used in hearings. Interpreters were used in 68% of hearings held (56% MRT and 89% RRT). The tribunals employ staff from diverse backgrounds covering more than 20 languages. Staff use professional interpreters to communicate with clients from non-English speaking backgrounds in hearings. The Stakeholder Engagement Plan for 2012-14 sets out how the tribunals will engage with stakeholders and the engagement activities planned for 2012-14 and beyond. Community liaison meetings were held twice during 2012-13 in Adelaide, Brisbane, Melbourne, Perth and Sydney. The tribunals have a formal complaints, compliments and suggestions process. | Achieved |

| 4. Acknowledge applications for review in writing within two working days | An acknowledgement letter was sent within two working days of lodgement in more than 74% of cases. | 74% |

| 5. Include a contact name and telephone number on all our correspondence | All letters include a contact name and telephone number. | Achieved |

| 6. Help you to understand our procedures | The tribunals provide applicants with information about tribunal procedures at several stages during the review process. The website includes a significant amount of information, including forms and factsheets. Case officers are available in the New South Wales and Victoria registries to explain procedures over the counter or by telephone. The tribunals have an email enquiry address that applicants can use to seek general information about procedures. | Achieved |

| 7. Provide information about where you can get advice and assistance | The website, service charter and application forms provide information about where applicants can get advice and assistance. Factsheet MR2: Immigration Assistance notifies applicants of organisations and individuals who can provide them with immigration assistance. The application forms R1, M1 and M2 explain in 28 community languages how applicants may contact the Translating and Interpreting Service (TIS). | Achieved |

| 8. Attempt to assist you if you have special needs | The tribunals employ a range of strategies to assist applicants with special needs. All offices are wheelchair accessible and hearing loops are available for use in hearing rooms. Whenever possible, requests for interpreters of a particular gender, dialect, ethnicity or religion are met. Hearings can be held by video conference. A national enquiry number 1300 361 969 is available from anywhere in Australia (calls are charged at the cost of a local call, more from mobile telephones). | Achieved |

| 9. Provide written reasons when we make a decision | In all cases, a written record of decision and the reasons for decision is provided to the applicant and to the department. | Achieved |

| 10. Publish guidelines relating to the priority we give to particular cases | Guidelines for the priority to be given to particular cases are published in the annual caseload and constitution policy, which is available on the website. | Achieved |

| 11. Publish the time standards within which we aim to complete reviews | Time standards are also set out in the caseload and constitution policy. | Achieved |

| 12. Abide by the Australian Public Service (APS) Values and Code of Conduct (staff) | New staff attend induction training, which includes training on the APS Values and the Code of Conduct. Ongoing staff complete refresher training at regular intervals. | Achieved |

| 13. Abide by the Member Code of Conduct (members) | All new members attend induction training, which includes the Member Code of Conduct. All members complete annual conflict of interest declaration forms and undergo performance reviews. | Achieved |

| 14. Publish information on caseload and tribunal performance | Information about caseload and performance in the current and previous financial years is published on the website under ‘statistics’. Further statistics, including those on the judicial review of tribunal decisions, are available in annual reports. | Achieved |

A high proportion of applicants have a language other than English as their first language. Clear language in letters and forms, and the availability of staff to assist applicants, are important to ensuring that applicants understand their rights, and tribunal procedures and processes.

The tribunal website is a significant information resource for applicants and others interested in the work of the tribunals. The publications and forms available on the website are regularly reviewed to ensure that information and advice are up-to-date and readily understood by clients.

The service charter is available on the website, along with the Strategic Plan, the Member Code of Conduct, the Interpreters’ Handbook and Principal Member directions as to the conduct of reviews. The ‘representatives’ webpage is aimed specifically at supporting representatives, by bringing together the most often used resources and information. A ‘frequently asked questions’ page answers questions most commonly asked by representatives.

The tribunals have offices in Melbourne and Sydney which are open between 8.30 am and 5.00 pm on working days. The tribunals have an arrangement with the AAT for counter services and hearings at AAT offices in Adelaide, Brisbane and Perth. The tribunals also have a national enquiry number (1300 361 969) available from anywhere in Australia (calls are charged at the cost of a local call, more from mobile telephones). Persons who need the assistance of an interpreter can contact the Translating and Interpreting Service on 131 450 for the cost of a local call.

The tribunals have a Reconciliation Action Plan, an Agency Multicultural Plan and a Workplace Diversity Program. Further information about these strategies and plans is set out in part 4.

Complaints

The service charter sets out the standards of service that

clients can expect. It also sets out how clients can comment on or complain about the services provided by the tribunals. The service charter is available on the ‘conduct of reviews’ page on

the website.

Most complaints to the tribunals are handled informally at the local level, which is consistent as most organisations dealing with the public. Formal complaints are handled in accordance with the tribunals’ complaints policy. Formal complaints are always in writing. Complaints about tribunal members are dealt with by the Principal Member. Complaints about staff or other matters are dealt with by the Registrar.

A person who is dissatisfied with how the tribunals have dealt with a matter or with the standard of service they have received, and who has not been able to resolve this by contacting the office or the officer dealing with their case, can forward a written complaint marked ‘confidential’ to the Complaints Officer.

Alternatively, a person can make a complaint to the Commonwealth Ombudsman, although the Ombudsman will not usually investigate a complaint that has not first been raised with the relevant agency.

The tribunals will acknowledge receipt of a complaint within five working days and aim to provide a final response within 20 working days of receipt of the complaint. The length of time before a final response depends on the extent of investigation which is necessary. If more time is required, because of the complexity of the complaint or the need to consult with other persons before providing a response, the tribunal will advise the complainant of progress in handling the complaint.

If a complaint is upheld, possible responses include an apology, a change to practice and procedure, or consideration of additional training and development for tribunal personnel.

During 2012-13, the tribunals received a total of 33 complaints from 29 individuals (23 from representatives, four from applicants and two from third parties). Table 7 shows the number of complaints made over the last three years.

| 2012-13 | 2011-12 | 2010-11 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MRT | |||

| Complaints resolved | 23 | 10 | 13 |

| Cases decided | 15,590 | 8,011 | 6,577 |

| Complaints per 1,000 cases | 1.5 | 1.2 | 2 |

| RRT | |||

| Complaints resolved | 10 | 8 | 8 |

| Cases decided | 3,757 | 2,804 | 2,604 |

| Complaints per 1,000 cases | 2.7 | 2.8 | 3.1 |

The 33 complaints made in 2012-13 were about the issues shown in table 8. A number of complaints raised multiple issues.

| Issue | MRT complaints | RRT complaints |

|---|---|---|

| Application of tribunal policy | 2 | 1 |

| Breach of privacy | - | 2 |

| Conduct of other parties in tribunal proceedings | 1 | - |

| Conduct of tribunal members | 18 | 4 |

| General procedural issues | 1 | 1 |

| Publication of decisions on the internet | - | 2 |

| Timeliness of reviews | 2 | 1 |

| Tribunal decisions | 1 | 2 |

The tribunals provided substantive responses to all 33 complaints, responding within 20 working days to 30 of the complaints (91%). The average number of days from complaint to final response was 10 working days.

Less than two complaints were received per 1,000 cases decided

In four complaints, all concerning the conduct of members during hearings, it was found that the members should have handled matters more appropriately. The Principal Member offered an apology in each case and raised the matters with the relevant members.

Table 9 sets out the complaints made to the Commonwealth Ombudsman over the last three years and the outcomes of the complaints resolved.

| 2012-13 | 2011-12 | 2010-11 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| New complaints | 1 | 1 | 26 |

| Complaints resolved | 1 | 1 | 24 |

| Administrative deficiency found | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Migration Agents

Sixty-four per cent of applicants were represented in 2012-13. With limited exceptions, a person acting as a representative is required to be a registered migration agent. Registered migration agents are required to conduct themselves in accordance with a code of conduct. The tribunals referred three matters to the Office of the Migration Agents Registration Authority (OMARA) during 2012-13 regarding the conduct of migration agents. OMARA is responsible for the registration of migration agents, monitoring the conduct of registered migration agents, investigating complaints and taking disciplinary action against registered migration agents who breach the code of conduct or behave in an unprofessional or unethical way.

Community and interagency liaison

The tribunals maintain regular engagement with a number of bodies with an interest in refugee and migration law, tribunal outcomes and merits review. The Stakeholder Engagement Committee oversees engagement and communication with external stakeholders. The Stakeholder Engagement Plan outlines the principles for engaging with clients and stakeholders, and strategies to support and improve communication and services.

137 people attended community liaison meetings in 2012-13

Twice-yearly community liaison meetings are held in Melbourne, Sydney, Brisbane, Adelaide and Perth to exchange information with key stakeholders. At community liaison meetings, updates are provided on legislative and corporate developments and attendees can raise matters that arise out of their dealings with the tribunals. The meetings are attended by representatives of migration and refugee advocacy groups, legal and migration agent associations, human rights bodies, the department and other government agencies.

The tribunals hold ‘open days’ or public information sessions each year. In 2013 MRT information sessions were held in Adelaide, Melbourne and Sydney during Law Week in May, and RRT information sessions were held in Brisbane, Melbourne, Perth and Sydney during Refugee Week in June. Information sessions involve hearing demonstrations and presentations from tribunal members and staff on processes and caseloads. These events are an opportunity for the public to get a better understanding of tribunal operations. There was a strong turnout at all events and positive feedback from those who attended. Due to a high demand for places, additional RRT sessions were also provided for the Australian Red Cross in Brisbane.

Regular meetings are held with the department, the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade and the AAT. Memoranda of understanding between the tribunals and these organisations reflect the statutory and operational relationships between the agencies.

Members and staff have continued to be active participants in several bodies, including the national and state chapters of the Council of Australasian Tribunals, the Australasian Institute of Judicial Administration, the Australian Institute of Administrative Law and the International Association of Refugee Law Judges.

Members and staff presented on the work of the tribunals at several events in 2012-13. In September 2012, the Deputy Principal Member spoke at the Migration Institute of Australia 2012 Conference on effective representation of clients before the tribunals. In March 2013, the Principal Member gave a presentation on current challenges for the RRT at the International Association of Refugee Law Judges Australasian Chapter Regional Conference. Both the Principal Member and Deputy Principal Member gave presentations as part of the Law Institute of Victoria Human Rights Series in May 2013. Significant speeches and presentations given by members and staff are published on the website.

Major reviews

Review of the increased workload of the tribunals

In December 2011, the former Minister the Hon Chris Bowen MP commissioned Professor the Hon Michael Lavarch, AO, to undertake a review of the increased workload of the tribunals. The review examined the increase in lodgements to both tribunals, including anticipated lodgements from unauthorised maritime arrivals. Minister Bowen released the Report on the increased workload of the MRT and the RRT on 29 June 2012 and supported the 18 recommendations.

All recommendations regarding the tribunals’ case management practices, member specialisation, staffing support and member resources have now been implemented. The tribunals and the department are working together to progress the implementation of the remaining recommendations that require legislative amendment or cooperation with the department.

Review of refugee status determination

In 2013, the government commenced a review of the refugee status determination system. The tribunals made available a highly experienced and knowledgeable senior member of staff to support the review. In addition the tribunals made a number of suggestions for improvements which would lead to more efficient and consistent merits review of refugee decisions.

Capability reviews

No capability reviews were undertaken for the tribunals during 2012-13.

Significant changes in the nature of functions or services

Transfer of Independent Protection Assessment Office functions

On 1 July 2012, the functions and resources of the office were transferred to the tribunals through a machinery-of-government change. As part of the transfer of functions, 52 ongoing public service staff were transferred from the department to the tribunals under section 72 of the Public Service Act.

Developments since the end of the year

Victoria Registry relocation

On 15 July 2013, the Victoria Registry relocated to new premises in the Melbourne central business district. The new premises has more hearing rooms, including purpose built video conference hearing rooms, and is located conveniently for applicants near major public transport links.

Country of origin information

On 1 July 2013, the tribunals’ country of origin information functions and staff formally transferred to the department. The change was effected through a machinery-of-government process. Country of origin information services will be provided to the tribunals by the department via a service level agreement that will govern the provision of products and services.

Case studies

Matters before the tribunals

The following case studies provide an insight into the range of matters which come before the tribunals. Summaries of decisions are published in a monthly bulletin, Précis, which is available on

the tribunal website.

MRT tourist visa – genuine visit to Australia – set-aside

The applicants, who were nationals of Pakistan, were the father and sister of an Australian permanent resident. They had been refused a visitor visa on the basis that there was a risk they would not return to Pakistan. They claimed that their visit to Australia was to coincide with the birth of the family’s first grandchild. Evidence was given that the father was a highly-regarded senior journalist and had travelled overseas on many occasions for work and religious purposes, as well as to visit a son in London. The sister was in high school at the time of the hearing. The applicants claimed that they resided in the Punjab area, which had not experienced problems like those in other provinces in Pakistan.

The MRT decided 1,090 visitor refusal cases in 2012-13; 56% were decided in favour of the applicant

The tribunal considered the applicants to be credible witnesses. It was satisfied that the father was in stable employment as a senior journalist in Pakistan, enjoyed the prestige and recognition of his work, and would not be able to be away from work for longer than two or three weeks. The tribunal also gave weight to the fact that his wife had recently visited Australia and had returned to Pakistan within the visa period. The tribunal accepted that the sister was intending to go to university in Pakistan. The tribunal noted a willingness to pay a security bond of up to $15,000 per applicant. The tribunal was satisfied that the applicants’ intention only to visit Australia was genuine.

MRT student visa – working over 20 hours per week – affirmed

The applicant’s previous student visa was cancelled in August 2010 for working more than 20 hours per week. The applicant claimed that he had completed aged care and community welfare studies in 2010 and that he wished to study a diploma of nursing. He claimed that for a period of three months in 2010 he had worked 22 hours per week at an aged care facility in order to meet his living costs in Australia. The applicant claimed that this work was related to his community welfare course, and that he felt obliged to advocate for patients for a couple of hours a week, although the advocacy work was not arranged by his education provider and he did not receive credit toward his study for that work. The applicant provided a payslip with his application which indicated that in his employment as a nursing assistant he had worked 52 hours during a 14 day period in July 2010.

The MRT decided 917 student cancellation cases in 2012-13; 13% were decided in favour of the applicant

The tribunal accepted the applicant’s evidence that he worked more than 20 hours a week only once or twice a month. It also accepted that the patient advocacy work was an activity the applicant performed for remuneration, and that the work was not specified as a requirement for the applicant’s course. The tribunal therefore found that the patient advocacy work was work for the purposes of compliance with the visa requirements. The tribunal found that the applicant was aware of his visa conditions and that he knew that what he was doing was wrong. It considered that the frequency and period of time over which the applicant knowingly worked in breach of his visa conditions meant that it was significant. Accordingly, the tribunal found that the applicant did not meet the requirements of the visa.

MRT skilled visa – Australian study requirement for the duration of study – affirmed

The applicant, a Sri Lankan national, had nominated the occupation of ‘marketing specialist’ for his skilled visa, which had the requirement of having completed 92 weeks of study within six months of applying for the visa. He claimed that in February 2008 he had commenced a Bachelor of Commerce degree at Deakin University. The applicant claimed that prior to arriving in Australia he had completed an Associate Degree in Business at the Perth Institute of Business and Technology (PIBT) via correspondence from Sri Lanka, which counted as 15 units towards the award of the Bachelor of Commerce degree. He claimed that during the following four semesters he completed the remaining nine out of the 24 units required for the award of the degree, finishing his studies at Deakin University in November 2009. The applicant’s representative claimed that the applicant was not aware of the 92 weeks study requirement at the time he lodged the visa application, and that he would have completed all 24 units in Australia if he was familiar with this requirement.

The MRT decided 4,576 skilled refusal cases in 2012-13; 23% were decided in favour of the applicant

The tribunal accepted that the applicant had undertaken the Bachelor of Commerce degree and had applied for the visa within the six months that the regulation allowed. The tribunal was not satisfied that the applicant met the requirements, noting the Federal Magistrates Court’s observation in Nayeem v MIAC [2010] that an applicant is required to have completed two academic years’ worth of study in Australia prior to applying for the visa, but the study load may be completed in no less than sixteen months, allowing for some degree of ‘fast-tracking’. As the applicant had completed nine subjects during his studies in Australia, the tribunal therefore found that the applicant had completed a total of 58.5 weeks’ study prior to applying for the visa, short of the 92 weeks required. Hence, the tribunal found that the applicant did not satisfy the Australian study requirement and he did not meet the requirements for the grant of the visa.

MRT distinguished talent visa – biographer of Ludwig Leichhardt – set-aside

The applicant had edited the life story of the explorer, Ludwig Leichhardt, based on the explorer’s diaries, letters and travel journals, and had authored a Leichhardt biography in German. The applicant was keen to undertake further work on unpublished Leichhardt manuscripts. He estimated that there were about 1,900 pages of text held in Australia which needed to be transcribed, translated and edited for publication. The applicant claimed he was proposing to undertake this work, with the goal of publishing a book to coincide with the 200th anniversary of Leichhardt’s birth in 2013. The applicant claimed that his skills rose above the ordinary in so far as his biography on Leichhardt was the first biography in German to be published and that it would become more widely known once it was published in English. A number of supporting letters were submitted on his behalf from various academics.

The MRT decided 21 distinguished talent applications in 2012-13; 33% were decided in favour of the applicant

The tribunal accepted that the applicant’s record of achievement was in the area of academia and research, and that he had published two significant works on Leichhardt. The tribunal found that, in addition to those published works, the applicant was known by peers in the area of academia and research as an expert on Leichhardt. The tribunal accepted that an English language edition of one of the applicant’s books was about to be published in Australia, that he maintained a website dedicated to Leichhardt, and that his peers internationally continued to refer to his work. The tribunal noted that he was at least 55 years old at the time of application and it was therefore required to consider if the applicant would be of exceptional benefit to the Australian community. The tribunal was satisfied that this was the case, and in particular, that without the research of the applicant in Australia, the Leichhardt materials would remain inaccessible to the public for a long period of time, if not forever. Hence, the tribunal found that the applicant met the requirements for the grant of the visa.

MRT partner visa – genuine relationship – set-aside

The Australian applicant claimed that he had worked in the mines in Western Australia for over two years on a ‘fly-in, fly-out’ basis. He claimed that his wife and child, who were currently in Morocco, would live permanently in Perth and that they would try to buy a house. The applicant claimed that he sent money to his wife and child each month, with the amount varying depending on how much they needed. His wife gave evidence to the tribunal that the refusal had affected her husband and that he was very unhappy as he had not yet seen his son. She claimed that this affected him at work and in his personal life, and that he had been involved in incidents at work because he was not as focused as he needed to be. The applicant had previously sponsored a former partner for a visa in February 2009, less than five years prior to this application, and this meant that the tribunal needed to be satisfied that there were compelling circumstances to permit him to sponsor another partner.

The tribunal found the couple to be validly married. It noted that they had given consistent and complementary evidence on the nature of the relationship and their commitment to each other, including the care of their Australian citizen child. The tribunal was therefore satisfied that at the time of application and time of decision, the applicants had a mutual commitment to a shared life as husband and wife to the exclusion of all others, and that the relationship was genuine and continuing. The tribunal then considered whether there were compelling circumstances affecting the sponsor, and it accepted the evidence from both of the applicants about the effect that the separation, and visa refusal had had on the applicant. The tribunal found that these were compelling circumstances and that the wife therefore satisfied the criteria for the grant of the visa.

RRT Turkey – Kurd – Alevi – set-aside

The RRT decided 42 cases from Turkey in 2012-13; 52% were decided in favour of the applicant

The applicant was an Alevi Kurd who claimed that the police would often come to his family’s apartment to search for illegal books, and that his father was taken into custody and accused of being a member and supporter of revolutionary groups. The applicant claimed that he assisted the Patriotic Revolutionary Youth Association and that he presented a radio program which was a voice of the Alevi-Kurdish people. He claimed that he often saw an undercover police car presence near the radio station, and that he was later detained and assaulted. While being detained by police he was forced to sign documents to say that he wanted to undertake his compulsory military service and that while on military service he was discriminated against and systematically insulted by his commanders. The applicant claimed that after returning from his studies in Australia, he was again detained by police and accused of financially assisting Kurdistan Workers’ Party organisations. The applicant claimed that he was a member of the Turkish-Kurdish and Alevi Associations in Australia.

The tribunal accepted that the applicant was of Kurdish ethnicity. Whilst it considered that merely being a Kurd was not sufficient to give rise to a well-founded fear of persecution in Turkey, the applicant in effect had claimed that he fell into the category of Kurds who faced harm due to their political activity. The tribunal was of the view that, given past incidents, the applicant would be viewed by the Turkish authorities as a supporter of pro-Kurdish political parties. It found there was a real chance that he would experience serious harm upon return to Turkey because of his Kurdish ethnicity, together with his political opinion. The tribunal was satisfied that the applicant would not be afforded state protection in Turkey, as the harm feared was from an instrument of the state. The tribunal therefore found that the applicant would be at risk of harm in any area of Turkey, and that he had a well-founded fear of being persecuted for a Convention reason.

The MRT decided 1,426 partner refusal cases in 2012-13; 53% were decided in favour of the applicant

RRT China – Catholic underground church – affirmed

The applicant, who originally arrived in Australia on a student visa, claimed to be a Catholic who regularly attended an underground house church in Fujian. She claimed that attendees of underground churches were persecuted by the government and the police. According to the applicant, police came and detained her husband on four occasions between 2002 and 2008, and she was also detained on one occasion. She claimed that she feared for the safety of her husband and child in China, but that she could not return because her husband could not support her. The applicant claimed to have attended church since arriving in Australia.

The RRT decided 564 cases from China in 2012-13; 18% were decided in favour of the applicant

The tribunal was satisfied that the applicant was a Catholic who practised that faith. The tribunal accepted that parishioners in China may have been detained in the past, but it concluded that there was no country information which indicated detention or adverse attention from the Chinese authorities of someone who was an ordinary member of an underground church in Fujian who did not hold a leadership position. The tribunal found that there were inconsistencies with the evidence regarding the detention incidents such that it was not satisfied the accounts were accurate. The tribunal formed the view that the applicant’s fear of persecution was only raised after initially making reference to economic circumstances, and it was not satisfied that the applicant held a well-founded fear of persecution for a Convention reason if she returned to China. The tribunal was also not satisfied that the applicant was a person in respect of whom Australia had complementary protection obligations.

RRT Afghanistan – association with the Afghan National Army – set-aside

The applicant claimed that his father was a village representative during the Najibullah government. He retired in 1990, becoming a village leader and was assassinated by unknown masked men. The applicant’s family suspected a local commander had killed his father after the local commander’s brother was kidnapped and probably killed. In 2011, the applicant’s younger brother was killed on his way to Kabul and the applicant thought someone had told the Taliban that his brother was working for the government. The applicant’s older brother, who was serving in the Afghanistan National Army (ANA), was ‘arrested’ by the Taliban after someone reported him to them for being government staff and he had not been seen since. The applicant claimed that someone from his village had seen the Taliban with his photo and the Taliban were stopping cars to ask if the applicant was in them. His wife and children were in Pakistan with his extended family, including the applicant’s mother, one sister, and the wife and children of his missing brother.

The RRT decided 494 cases from Afghanistan in 2012-13; 84% were decided in favour of the applicant

The tribunal found that the applicant was a member of a particular social group because of his family’s association with the ANA, the Najibullah government and the murder of the brother of a local commander. The tribunal accepted the applicant’s evidence, including the key claim that he worked for the ANA. He described various matters in sufficient detail to satisfy the tribunal that he was a witness of truth. The tribunal noted the ANA claim was first made in pre-hearing submissions and the applicant did not provide a statement in support of these claims; however, the applicant was able to allay the tribunal’s concerns. The tribunal further accepted the applicant’s evidence that this fact was well known in his village and that he was perceived as a person who supported the central government. The tribunal accepted that one of the applicant’s brothers was killed on his way to Kabul and that it was possible that the applicant’s other brother was kidnapped (and possibly killed) for reasons of his political opinion, because he was with the ANA. The tribunal remitted the matter to the department with the finding that the applicant was a person to whom Australia had protection obligations under the Refugees Convention.

RRT Nepal – Congress Party member – affirmed

The applicant, who was originally in Australia on a student visa, claimed that he was a member of the Congress Party in Nepal and that he undertook various party activities. The applicant claimed that the ruling United Communist Party (Maoists) began to cause trouble for him due to these activities, and that they would continuously come to his shop, threatening him with harm. The applicant claimed that he was arrested by Maoists for protesting about human rights and political freedom before the election in 2009, and that he was attacked and beaten after the election on his way home from a party meeting. The applicant claimed that on another occasion he was approached by Maoists and beaten, sustaining injuries which required medical treatment. The applicant claimed that after he came to Australia, his family told him that Maoists were coming to look for him. He claimed that he did return to Nepal for a brief period to visit his sick son, although he did not return to his village, but rather his family came to see him in Kathmandu.

The RRT decided 110 cases from Nepal in 2012-13; 6% were decided in favour of the applicant

The tribunal noted inconsistencies between the applicant’s written statements and his evidence at hearing about when he was attacked by Maoists. His statement also omitted any mention of Maoists coming to his shop and demanding to see him. The tribunal found this to be prominent in the applicant’s account of harm received from the Maoists, and it did not believe that he would fail to mention this in his statement. The tribunal did not accept that the applicant would have taken the risk of returning to Nepal in the circumstances as claimed, and it found that the fact that he had was evidence that he was not genuinely in fear of harm. The tribunal considered that even if he had remained in Kathmandu, the applicant would not have taken the risk of going there when he had fled the country to save his life. The tribunal’s concerns about the applicant’s credibility led it to find that the account of events on which his protection claims were based was false. Hence, the tribunal was not satisfied that the applicant was a person to whom Australia had protection obligations under the Refugees Convention or complementary protection criteria.

RRT Sri Lanka – imputed Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) supporter – affirmed

The applicant said he feared persecution in Sri Lanka because of his Tamil ethnicity and an imputed political opinion as a supporter of the LTTE and opponent of the government. He asserted that he would be imputed as being opposed to the government because he operated a repair shop that had occasionally repaired equipment for the LTTE, and his relative was an LTTE member. The applicant claimed that his problems started in 2003 when people in the area told the Criminal Investigation Department (CID) that he was working for the LTTE. He said he was detained, and held for various periods of time and tortured. The applicant denied ever having been part of the LTTE himself, but said a relative had worked for them. He claimed that the CID knew about this and had asked him about his relative, even asking him to provide a photograph of her.

The RRT decided 422 cases from Sri Lanka in 2012-13; 37% were decided in favour of the applicant

The tribunal did not find the applicant to be credible, and considered that he had embellished and exaggerated aspects of his claims to support his application. While he claimed to fear harm because his relative allegedly worked for the LTTE, the tribunal noted this claim was not made as part of his initial protection application. The tribunal accepted the applicant had repaired equipment as claimed and that he may have repaired equipment owned by the LTTE. The tribunal found the applicant had provided inconsistent and contradictory information about the duration of this adverse treatment at the hands of the CID. The tribunal noted independent information that the situation for Tamils in Sri Lanka had improved significantly since the cessation of hostilities between the government and LTTE in 2009. As a result, the tribunal did not accept the applicant’s claim that simply being of Tamil ethnicity was of itself sufficient to give rise to a real chance of persecution. Whilst the tribunal was prepared to accept that the applicant had come to the adverse attention of authorities during the conflict in Sri Lanka, it did not consider he was a person who may still face significant harm. The tribunal was also not satisfied that the applicant met the complementary protection criterion.

![Australian Government - Migration Review Tribunal - Refugee Review Tribunal [header logo image]](img/header/img-hdr-logo.jpg)

![Annual Report 2010-2011 [header text image]](img/header/img-hdr-ar-2011-2012.jpg)