Part 3 – Performance report

Contents

- Performance framework

- Financial performance

- Overview of caseload

- Lodgements

- Conduct of reviews

- Interpreters

- Outcomes of review

- Timeliness

- Judicial review

- Social justice and equity

- Complaints

- Migration agents

- Community and interagency liaison

- Major reviews

- Significant changes in the nature of functions or services

- Developments since the end of the year

The tribunals contributed to Australia’s migration and refugee programs during the year through the provision of quality and timely reviews of decisions.

Performance framework

The tribunals operate in a high volume decision making environment where the case law and legislation are complex and technical. The tribunals have identical statutory objectives, set out in sections 353 and 420 of the Migration Act:

The tribunal shall, in carrying out its functions under this Act, pursue the objective of providing a mechanism of review that is fair, just, economical, informal and quick.

The key strategic priorities are to meet these statutory objectives through the delivery of consistent, high quality reviews, and timely and lawful decisions.

Each review must be conducted in a way that ensures, as far as practicable, that the applicant understands the issues and has a fair opportunity to comment on or respond to any matters which might lead to an adverse outcome.

The tribunals also aim to meet government and community expectations and to have effective working relationships with stakeholders. These priorities are reflected in the tribunals’ strategic plan.

For 2013–14, one outcome was specified in the Portfolio Budget Statement:

To provide correct and preferable decisions for visa applicants and sponsors through independent, fair, just, economical, informal and quick merits reviews of migration and refugee decisions.

The tribunals had one program contributing to this outcome, which was:

Final independent merits review of decisions concerning refugee status and the refusal or cancellation of migration and refugee visas.

For 2013-14 the tribunals finalised 24,729 decisions against a caseload target of 24,000 decisions.

Table 2 summarises performance against the program deliverables and key performance indicators that were set out in the Portfolio Budget Statement.

| Measure | Result |

|---|---|

| Key performance indicators | |

| Less than 5% of tribunal decisions set-aside by judicial review | 0.3% of MRT and 0.8% of RRT decisions made in 2013–14 were set-aside by judicial review |

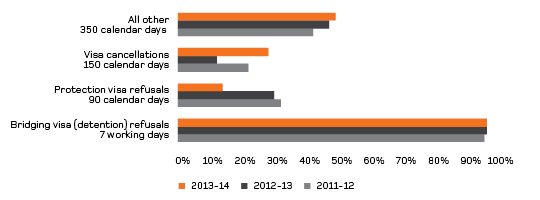

| 70% of cases decided within time standards | 96% of bridging visa (detention) refusals were decided within seven working days 16% of protection visa refusals were decided within 90 calendar days 28% of visa cancellations were decided within 150 calendar days 49% of all other visa refusals were decided within 350 days |

| Less than five complaints per 1,000 cases decided | Less than three complaints per 1,000 cases decided (56 complaints) |

| At least 4,500 decisions published | 4,611 decisions published |

The timeliness of reviews has been affected by large increases in lodgements and cases on hand over the past few years. Lodgements increased by 9% in 2013–14, the main contributor to the increase being the large number of applications for RRT review of unauthorised maritime arrival cases. The time taken to finalise reviews of visa refusal decisions other than protection visa decisions improved from an average of 58 weeks at the end of 2012–13 to 52 weeks at the end of 2013–14.

Financial performance

The MRT and the RRT are prescribed as a single agency, the ‘Migration Review Tribunal and Refugee Review Tribunal’ for the purposes of the FMA Act and the PGPA Act. The tribunals are funded based on a model which takes into account the number of reviews finalised. The tribunals’ base funding in 2013-14 covered an amount to finalise 18,000 reviews. This funding is adjusted at a marginal rate per review based on actual reviews finalised whether above or below that number. 24,729 reviews were finalised in 2013-14 and the revenue as set out below takes into account an adjustment to appropriation based on the actual number of reviews finalised.

The revenues from ordinary activities totalled $80.78 million and expenditure totalled $72.25 million, resulting in a net surplus of $8.53 million and depreciation worth $3.61 million.

The tribunals administer application fees on behalf of the government. Details of administered revenue are set out in the financial statements. The financial statements for 2013-14, which are set out in part 5, have been audited by the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) and received an unqualified audit opinion.

Overview of caseload

MRT and RRT caseload

The tribunals received 22,289 lodgements during the year, decided 24,729 cases and had 16,970 cases on hand at the end of the year. Table 3 provides an overview of the tribunals’ caseload over the past three years.

| 2013–14 | 2012–13 | 2011–12 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MRT | |||

| On hand at start of year | 17,437 | 16,863 | 10,786 |

| Lodged | 15,426 | 16,164 | 14,088 |

| Decided | 21,144 | 15,590 | 8,011 |

| On hand at end of year | 11,719 | 17,437 | 16,863 |

| RRT | |||

| On hand at start of year | 1,973 | 1,501 | 1,100 |

| Lodged | 6,863 | 4,229 | 3,205 |

| Decided | 3,585 | 3,757 | 2,804 |

| On hand at end of year | 5,251 | 1,973 | 1,501 |

| TOTAL MRT AND RRT | |||

| On hand at start of year | 19,410 | 18,364 | 11,886 |

| Lodged | 22,289 | 20,393 | 17,293 |

| Decided | 24,729 | 19,347 | 10,815 |

| On-hand at end of year | 16,970 | 19,410 | 18,364 |

*Additional statistical information regarding the MRT and RRT caseloads is provided in Appendix A.

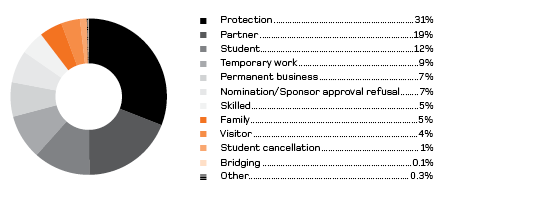

Figure 1 displays each case category as a percentage of the caseload on hand at 30 June 2014.

Figure 1 – MRT and RRT cases on hand as at 30 June 2014*

* In 2013–14, the composition of the MRT ‘other’ and ‘visitor’ case categories changed. Visa cancellations were moved from the ‘other’ case category to their respective case categories (e.g. partner visa cancellations moved from ‘other’ to the ‘partner’ case category). Subclass 417 (Working Holiday) visa reviews were removed from the ‘other’ case category to the ‘visitor’ case category. These changes have been applied to the statistical data for previous years in this report. As a result, MRT caseload category data for 2011–12 and 2012–13 in this report will vary from data included in previous annual reports.

Lodgements

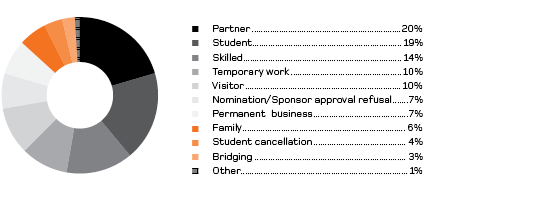

The MRT has jurisdiction to review a wide range of visa, sponsorship and other decisions for migration and temporary entry visas. In 2013–14, the MRT received 15,426 lodgements, which included significant increases in partner, nomination/sponsor approval refusal, visitor and temporary work lodgements. There was a significant decrease in skilled lodgements and a lesser decrease in family and student lodgements in 2013–14. Figure 2 provides an overview of MRT lodgements by case category.

Figure 2 – MRT lodgements by case category

The MRT’s jurisdiction to review decisions about visas applied for outside Australia depends on whether there is a requirement for an Australian sponsor or for a close relative to be identified in the application. These cases are mainly in the permanent business, visitor, partner and family categories. In 2013–14, approximately 21% of applications for review of visa refusal decisions by the MRT related to persons outside Australia seeking a visa.

Partner and family caseload highlights

Partner refusal

The tribunals experienced strong growth in the lodgement of applications for review of partner visa decisions in 2013–14, increasing from 12% of all MRT lodgements in 2012–13 to 20% in 2013–14. As a result, applications for review of partner visa refusal decisions became the largest category of MRT lodgements in 2013–14.

Decisions on partner refusal reviews represented 11% of all MRT decisions in 2013–14, up from 9% in 2012–13, reflecting the growth in the caseload and allocation of additional member resources. The MRT set-aside, or set-aside and remitted, the primary decision in 45% of cases involving partner visa reviews, the second highest rate of all MRT case categories in 2013–14 after visitor visa reviews. This is down from a set-aside rate of 52% in 2012–13.

The time taken from lodgement to decision for partner visa reviews improved from an average of 512 calendar days in 2012–13 to an average of 449 days in 2013–14.

Case Study: MRT partner visa – genuine relationship – remitted

The delegate refused to grant the visa on the basis that the applicant did not satisfy cl.820.211 and cl.820.221 of Schedule 2 to the Regulations. The delegate was not satisfied that the parties were in a genuine and continuing relationship. The parties claimed that they commenced living together in 2010 and that they married in 2011. They claimed that the sponsor’s parents were not told of the wedding because they did not approve of the relationship, but once the sponsor’s parents got to know the applicant, they approved of him and supported the relationship. The sponsor’s father claimed that he was initially concerned that the applicant may have used his daughter to obtain permanent residency; however, he was no longer concerned. The parties claimed that they have attended many family engagements with the sponsor’s family and relatives, and the sponsor was regularly in contact with the applicant’s relatives in India.

The tribunal found all the witnesses gave credible and open evidence. The tribunal found that the applicant and the sponsor gave consistent information as to where they lived, their household and financial arrangements, and their working situation. The tribunal found that the parties shared a household together; they contributed to the maintenance of their home; shared their expenses and pooled their financial resources. Furthermore, the tribunal was satisfied that the social aspects of the relationship clearly indicated that the applicant and the sponsor presented themselves as being married to each other and that this relationship was accepted by all their friends and relatives. The tribunal found that although the applicant and the sponsor had not disclosed that they were married at the time of application, this did not mean that the relationship was not genuine and continuing. The tribunal was satisfied that the parties were in a genuine, continuing and exclusive relationship and therefore the applicant met cl.820.211 and cl.820.221. The tribunal remitted the visa application to the department to consider the remaining criteria for the grant of the visa.

Family refusal

Lodgements of applications for review of family visa refusal decisions in 2013–14 were below 2012–13 levels, with 885 review applications received in 2013–14 compared to 1,175 in 2012–13.

The MRT set-aside, or set-aside and remitted, the primary decision made by a delegate of the Minister in 36% of all family visa refusal cases in 2013–14. The average days from lodgement of an application for review to MRT decision improved from 480 calendar days in 2012–13 to 338 days in 2013–14. A combination of lower than expected application numbers and improved timeliness in MRT decision making reduced the on hand caseload from 1,200 cases at 1 July 2013 to 795 at 30 June 2014.

Case Study: MRT child visa – orphan relative – under the age of 18 – set-aside

The sponsor claimed the applicant was 17 years and 9 months old at the time of the visa application as did the applicant who supplied documents from an Afghanistan Consulate in Pakistan to support his claim. The applicant claimed that because he had left his country of birth, Afghanistan, at a young age, the only other proof of age he could provide was an education document. The applicant also provided various photographs of himself taken at different times in an attempt to corroborate his claimed age.

The tribunal accepted that documentation relating to births and deaths in Afghanistan and for Afghan nationals in Pakistan is inherently unreliable, and on this basis it was also inclined to give limited weight to the documentary evidence submitted by the applicant to establish his correct date of birth. The tribunal recognised the difficulty in assessing the age of the applicant in circumstances where reliable documentary evidence was not available. In its findings the tribunal gave significant weight to the consistent and credible information provided by the applicant and his sponsor. The tribunal found that in the absence of any specific adverse information to contradict its findings, it was appropriate to give the applicant the benefit of the doubt about the matter of his age, and accepted on balance, that the applicant’s date of birth was as claimed. The tribunal found that the applicant had not turned 18 at the time of application and therefore met r.1.14(a)(i). It followed that the applicant also satisfied cl.117.211. The tribunal noted that the applicant did not continue to satisfy cl.117.211 at the time of the decision but only because he had since turned 18. It followed that the tribunal found he met cl.117.221 at the time of decision. The tribunal remitted the visa application to the department to consider the remaining criteria for the grant of the visa.

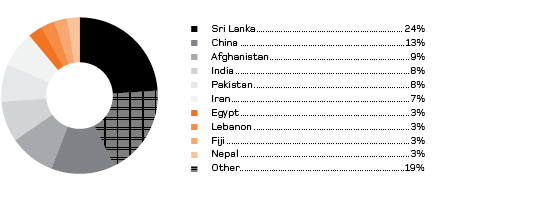

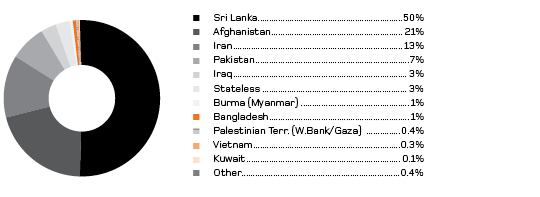

The RRT has jurisdiction to review decisions to refuse protection visas. In 2013–14, the RRT received 6,863 lodgements, including 3,080 applications from unauthorised maritime arrivals. RRT lodgements in 2013–14 were higher than projected as a result of a higher number of refusals of unauthorised maritime arrival protection visa applications by delegates of the Minister. Applications for review to the RRT were received from persons from 100 different countries. Nationals of six countries – Sri Lanka, China, Afghanistan, India, Pakistan and Iran – comprised 70% of all RRT lodgements. The largest number of applications received was from nationals of Sri Lanka, at 24% of all RRT applications lodged. China was the second most common country of origin for RRT applicants, representing 13% of all RRT applications received. Around 95% of all applications received from unauthorised maritime arrivals were from nationals of Sri Lanka, Afghanistan, Iran, Pakistan and Iraq.

Figures 3, 4 and 5 provide an overview of RRT lodgements by the applicant’s country of origin. Figure 3 includes all lodgements received by the RRT, while Figure 4 displays the countries of origin of unauthorised maritime arrivals only. Figure 5 displays the countries of all other RRT applicants (excluding unauthorised maritime arrivals).

Figure 3 – RRT lodgements by country

Nationals of six countries - Sri Lanka, China, Afghanistan, India, Pakistan and Iran – comprised 70% of all RRT lodgements

Figure 4 – RRT lodgements by country for unauthorised maritime arrivals

Figure 5 – RRT lodgements by country for applicants other than unauthorised maritime arrivals

Sri Lanka and Pakistan caseload highlights

Sri Lanka

RRT lodgements by applicants from Sri Lanka comprised 24% of all RRT lodgements in 2013–14, making Sri Lanka the most common country of origin for RRT applicants. Lodgements by applicants from Sri Lanka increased by 135% on 2012–13 levels, in large part due to a high number of applications (94% or 1,553) received from unauthorised maritime arrivals from Sri Lanka.

In 2013–14, RRT Sri Lanka decisions comprised 11% of all RRT decisions. The RRT set-aside, or set-aside and remitted, the primary decision made by the department in 22% of all Sri Lanka cases. The RRT remitted eight cases to the department on complementary protection grounds involving applicants from Sri Lanka in 2013–14, compared to two cases in 2012–13.

As a result of the high level of lodgements received in 2013–14, and a Ministerial Direction requiring the tribunals to give priority to applications received from applicants other than unauthorised maritime arrivals, review applications from Sri Lanka comprised 30% of the active RRT caseload at 30 June 2014.

Case Study: RRT Sri Lanka – imputed Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) supporter – affirmed

The applicant claimed that he worked as a fisherman during the fishing season and did labouring work if it was available. He claimed that he was asked by the army in 2010 to do labouring work for them at an army camp. The applicant claimed that on a number of occasions he was told by officers to go to a room at the camp where they assaulted him, and that they used a burning cigarette to scar his body. He claimed that Criminal Investigations Division (CID) officers also visited his family home carrying guns, alleging that his father was involved with the LTTE and ordering that the applicant and his brother report to the camp. He claimed that this happened on a number of occasions, which forced him to leave the village and eventually leave Sri Lanka by boat.

The tribunal found contradictions in relation to the applicant’s claim regarding the CID’s visits to his home, and it also noted inconsistencies in his evidence as to when he departed his village and whether the CID visited again after he left. The tribunal found that the applicant had displayed a ‘complacent’ attitude to the CID’s visit in 2011 and was not fearful of the consequences, despite not complying with their order to report to the army base. The tribunal did not accept that the CID visited his house and that his father was being investigated for alleged links to the LTTE. Neither did it accept that the applicant did labouring work for the army or was assaulted. As such, the tribunal found that the applicant did not have a well-founded fear of being persecuted for a Convention reason, and that he did not meet the complementary protection criteria.

Pakistan

RRT lodgements by applicants from Pakistan comprised 8% of all RRT lodgements in 2013–14. Review lodgements where the applicant was an unauthorised maritime arrival comprised 43% of Pakistan lodgements to the RRT in 2013–14. The majority of RRT decisions where the applicant claimed citizenship of Pakistan were from applicants other than unauthorised maritime arrivals: 289 or 92%. This reflects a Ministerial direction requiring the tribunals to give priority to applications received from applicants other than unauthorised maritime arrivals.

The RRT set-aside, or set-aside and remitted, the primary decision in 41% of cases involving applicants from Pakistan. The RRT remitted 13 cases to the department on complementary protection grounds involving applicants from Pakistan in 2013–14, compared to two cases in 2012–13.

Case Study: RRT Pakistan – Shi’a – female teacher of girls – set-aside

The applicant claimed to fear persecution by Sunni extremists in Pakistan as a consequence of her Shi’a religion, her voluntary work at a Shi’a mosque, and her role as a female teacher of girls. She claimed to have volunteered as a security assistant for women at the mosque, and that on one occasion she had hindered a potential attack which attracted the adverse attention of Sunni extremists. The applicant claimed that she then received telephone calls from members of Lashkar-e-Jhangvi threatening her with death, and that she was later attacked in the street and told to stop her voluntary and teaching work and to stay at home. The telephone calls stopped when she quit her voluntary work. However, when she resumed voluntary work at the mosque, the applicant claimed that she received another threatening telephone call and was later attacked by someone with a knife, whose attempts to harm her were foiled by passing Pakistan Rangers.

The tribunal considered the evidence presented to be credible and found that the applicant feared persecution in Pakistan due to her Shi’a faith, her status as a female teacher, a volunteer at a Shi’a mosque, and her imputed anti-extremist opinion. The tribunal noted independent information which indicated that the Pakistani government could not guarantee security to its population, that various Sunni extremist groups, including Lashkar-e-Jhangvi, were opposed to the education of girls and professional women outside the home, and had subjected Shi’a Muslims to many violent and lethal attacks across Pakistan. The tribunal concluded that the applicant could not relocate within Pakistan, as her dedication to her faith and her role as teacher of girls would attract the adverse attention of Sunni extremists wherever she went. The tribunal therefore found that the applicant met the criteria for the grant of a protection visa.

The tribunals introduced an online lodgement facility for applicants on 31 January 2014. From this date, around 44% of all applications to the tribunals were lodged online. The rate of online lodgements as a percentage of all lodgements steadily increased, with 60% of all lodgements in June 2014 made online.

Applicants to the tribunals tend to be located in the larger metropolitan areas. Around 40% of all applicants resided in New South Wales, an increase of around 3% from 2012–13 with the majority of applicants located in the Sydney region. Approximately 31% of applicants resided in Victoria, 11% in Queensland, 9% in Western Australia, 5% in South Australia, 1% each in the Australian Capital Territory and in the Northern Territory, and less than 1% in Tasmania. Over the past five years, the proportion of lodgements from New South Wales has decreased significantly – from 52% of all lodgements received in 2008–09 to 40% in 2013–14. The decline in the proportion of lodgements in New South Wales over the last five years has been offset by increases in lodgements in Victoria, Queensland, Western Australia and South Australia.

Cases involving applicants in immigration detention comprised 4% of applications received in 2013–14.

Conduct of reviews

The proceedings of the tribunals are inquisitorial and do not take the form of litigation between parties. The review is an inquiry in which the member identifies the issues or criteria in dispute, initiates investigations or inquiries to supplement evidence provided by the applicant and the department and ensures procedural momentum. At the same time, the member must maintain an open and impartial mind.

In 2013–14, there were 20,035 MRT hearings (including cases allocated to a hearing list) and 4,411 RRT hearings arranged. There were 12,326 MRT and 2,991 RRT cases with a hearing held that were completed or adjourned. The remaining hearings were postponed, rescheduled or did not proceed as the applicant did not attend.

Cases where no hearing is arranged include those where a decision favourable to the applicant is made or the applicant withdraws prior to a hearing being arranged. Favourable decisions were made without the need for a hearing in 9% of MRT cases and in 1% of RRT cases.

Video links were used in 11% of MRT hearings and telephone in 10% of MRT hearings. The average duration of MRT hearings was 54 minutes, while the average duration of RRT hearings was 139 minutes. Two or more hearings were held in 10% of RRT cases and 2% of MRT cases.

Hearing lists enable a number of cases to be heard by the presiding member consecutively and are open to the public. In 2013–14, there were 6,575 cases listed in 1,000 hearing lists, mainly in the skilled and student caseloads. Of these, 3,523 cases with a hearing held were completed or adjourned with the average duration of a hearing at 22 minutes. Hearing lists made up 29% of all MRT hearings completed.

Skilled and student refusal caseload highlights

Skilled refusal

In 2013–14, the tribunals experienced declining lodgements of applications for review of skilled visa refusal decisions, down 51% compared to 2012–13. The decline was most notable for reviews of Subclass 485 (Temporary Graduate) visa primary decisions, down 83% compared to 2012–13.

The MRT significantly reduced the quantity and age of skilled visa refusal cases on hand in 2013–14, down from 3,325 cases at 1 July 2013 to 841 cases at 30 June 2014. The number of cases aged over 275 days from lodgement of application reduced from 1,561 at 30 June 2013 to 393 at 30 June 2014. This was due to declining lodgements and the use of hearing lists. Hearing lists enable a number of cases to be heard by the presiding member consecutively. Most skilled visa refusal reviews are now conducted in this manner, with the exception of particularly complex or sensitive matters. Around 56% of skilled visa refusal decisions involved the use of a hearing list.

The MRT set-aside, or set-aside and remitted, the primary decision made by the department in 22% of all skilled visa refusal reviews in 2013–14, consistent with 2012–13 levels.

Case Study: MRT skilled visa – qualifying score – remitted

The applicant, who was 30 years old at the time of application, claimed that she had been employed as a psychologist in India for several years after obtaining her qualifications. She claimed that she did not include details of this employment in her application as her previous migration agent had advised her that the department would not accept this information without taxation records and, in any case, she had already achieved the requisite 120 points without the need to provide these details. The applicant claimed that much of her work had been for charitable organisations, and that her wage was below the threshold required for taxation to be paid. She provided various documents in relation to her employment in India, as well as the results of an International English Language Testing System (IELTS) test in which she obtained scores of 8.0; 6.0; 6.5 and 6.5. The applicant’s representative requested further time to enable the applicant to undertake a further IELTS test in order for her to achieve a score of at least seven in all four components.

The tribunal assessed the applicant against Schedule 6B; however, given that the work experience which the applicant relied upon was not within the relevant time frame, it found that her qualifying score did not equate to the required 120 points. The tribunal then assessed the applicant against Schedule 6C, and it found that she was eligible for maximum points due to her age; that she also achieved points for her overseas work experience given that she had worked as a psychologist in India for a period totalling at least 60 months in the 10 years prior to the date of application; that she achieved points for obtaining work experience in Australia, and that she achieved points for educational and Australian study qualifications. The tribunal noted that at the date of the primary assessment, the pass mark was 65 points and the pool mark was also 65 points, and after making its assessment the tribunal found that the applicant was entitled to a maximum of 65 points under the points test. Accordingly, the tribunal found that the applicant had achieved the qualifying score required to pass the points test, and remitted the application for the visa to the department to consider the remaining criteria for the visa.

Student refusal

The tribunals made significant progress in reducing the number of applications for review of student refusal decisions on hand in 2013–14, down 60% to 1,944 cases at 30 June 2014. The reduction in the active caseload can be attributed to declining lodgements and the high number of decisions made using hearing lists. Lodgements of applications for review of student visa decisions declined by 17% in 2013–14 compared to 2012–13.

Hearing lists enable a number of cases to be heard by the presiding member consecutively, reducing the need to repeat steps such as addressing introductory matters with each applicant individually. The majority of student visa refusal reviews are now conducted in this manner, with the exception of particularly complex or sensitive matters. Around 59% of reviews of student visa refusal decisions made in 2013–14 involved the use of a hearing list.

Student visa refusal reviews made up the largest category of MRT decisions in 2013–14 at 26% of all MRT decisions, or 5,896 decisions. This was a 62% increase in decision making in this category compared to 2012–13. The MRT set-aside, or set-aside and remitted, the primary decision in 26% of all student refusal cases in 2013–14, compared to 23% in 2012–13. The time taken from lodgement to decision for student visa reviews improved from an average of 535 calendar days in 2012–13 to an average of 417 days in 2013–14.

Case Study: MRT student visa – genuine temporary entry – affirmed

The delegate refused to grant the visa on the basis that the applicant did not satisfy the requirements of cl.570.223 of Schedule 2 to the Regulations. The delegate was not satisfied that the applicant genuinely intended to stay in Australia on a temporary basis. The delegate found that the applicant had applied for the visa in order to extend her stay in Australia. The applicant claimed that despite her study in Australia, her English was not sufficient to assist with business documentation in her father’s business in Thailand. She claimed she would like to increase her English competency and complete a Bachelor degree course in Australia, after which time she would return to Thailand to take over her father’s business.

The tribunal was not satisfied that the applicant was a genuine temporary entrant to Australia for the purpose of study. The tribunal found the applicant was 36 years of age, she was not currently enrolled in a course of study, she had previously successfully completed five and a half years of study in Australia and she had spent very little time outside Australia since first entering the country. It also found on the applicant’s evidence that her intention was to undertake a further English course, which she had previously successfully completed, and then apply to undertake a Bachelor degree course. The tribunal found these actions would extend the applicant’s stay for a further three and a half years. On the basis of the applicant’s circumstances and immigration history, the tribunal was not satisfied the applicant intended to visit Australia on a temporary basis and did not meet cl.570.223(1)(a). Accordingly, the tribunal was not satisfied that the applicant met the criteria for the grant of the visa.

Interpreters

High quality interpreting services are fundamental to the work of the tribunals. In 2013–14, interpreters were required for 57% of MRT hearings and 85% of RRT hearings equating to over 11,000 hearings. Interpreters were required in approximately 98 languages and dialects, up from 94 the previous year.

Interpreters in 98 languages and dialects were used in tribunal hearings

The tribunals’ Interpreter Advisory Group (IAG), a national committee comprising members and staff, works to uphold best-practice interpreting at hearings. In 2013–14 the IAG facilitated training of RRT members in the use of interpreters and worked closely with our interpreter service provider, ONCALL Interpreters and Translators. In liaison with ONCALL the tribunals provided training sessions to interpreters in Sydney, Melbourne, Adelaide, Perth and Brisbane to assist with the provision of quality interpreting services.

The Interpreters’ Handbook, which provides comprehensive guidance for interpreters working in the tribunals as well as others involved in the review process, was revised and updated and is available on the tribunals’ website.

Outcomes of review

A written statement of decision and reasons is prepared in each case and provided to both the applicant and the department.

The MRT set-aside, or set-aside and remitted, the primary decision in 30% of cases decided and affirmed the primary decision in 50% of cases decided. The remaining cases were either withdrawn by the applicant or were cases where the tribunal decided it had no jurisdiction to conduct the review. The MRT set-aside rate in 2013–14 was consistent with the rate of 29% in 2012–13.

The RRT remitted the primary decision in 22% of cases decided and affirmed the primary decision in 72% of cases decided. The remaining cases were either withdrawn by the applicant or were cases where the tribunal decided it had no jurisdiction to conduct the review. The RRT remit rate was significantly lower than the rate of 37% in 2012–13. The decrease in the RRT remit rate in 2013–14 was partly a result of finalising fewer applications from unauthorised maritime arrivals, in accordance with a Ministerial Direction requiring the RRT to prioritise applications from persons other than unauthorised maritime arrivals, which came into effect on 1 July 2013. Many unauthorised maritime arrivals came from countries where there have been relatively high rates of acceptance of claims at both the primary and review level.

Most RRT remittals were on the basis that the applicant was a refugee. There were also 48 cases remitted with a direction that the applicant met the complementary protection criterion. The fact that a decision is set-aside by the tribunal is not necessarily a reflection on the quality of the primary decision, which may have been correct and reasonable based on the information available at the time of the decision. Table 4 below provides an overview of the outcomes of review for the past three financial years.

| 2013–14 | 2012–13 | 2011–12 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MRT | |||

| Primary decision set-aside or remitted | 6,319 | 4,514 | 2,912 |

| Primary decision affirmed | 10,668 | 7,121 | 3,133 |

| Application withdrawn by applicant | 3,206 | 2,661 | 1,180 |

| No jurisdiction to review* | 951 | 1,294 | 786 |

| Total | 21,144 | 15,590 | 8,011 |

| RRT | |||

| Primary decision set-aside or remitted | 779 | 1,372 | 750 |

| Primary decision affirmed | 2,591 | 2,205 | 1,899 |

| Application withdrawn by applicant | 145 | 86 | 86 |

| No jurisdiction to review* | 70 | 94 | 69 |

| Total | 3,585 | 3,757 | 2,804 |

* No jurisdiction decisions include applications not made within the prescribed time limit, not made in respect of reviewable decisions and not made by a person with standing to apply for review.

Applications for review typically address the issues identified by the primary decision maker by providing submissions and further evidence to the tribunal. By the time of the tribunal’s decision, there is often considerable additional information before the tribunal. There may also be court judgments or legislative changes which affect the outcome of the review.

Applicants were represented in 62% of cases decided. Representation was most commonly by a registered migration agent. In cases where applicants were represented, the set-aside rate was higher than for unrepresented applicants. The difference was more notable for RRT cases, where the set-aside rate was 29% for represented applicants and 9% for unrepresented applicants. Unrepresented applicants may not have sought advice on their prospects of success before applying for review or may have applied despite obtaining advice that the prospects of success were low. Only 70% of unrepresented applicants to the RRT attend hearings, compared to almost 86% of represented applicants. For the MRT, there was also a significant difference in outcome for unrepresented applicants. The set-aside rate was 34% for represented applicants and 23% for unrepresented applicants.

22% of RRT and 30% of MRT cases were decided in favour of the applicant

A total of 396 cases (approximately 2% of the cases decided) were referred to the department for consideration under the Minister’s intervention guidelines. These cases raised humanitarian or compassionate circumstances which members considered should be drawn to the attention of the Minister.

China and Lebanon caseload highlights

China

Lodgements by applicants from China represented 13% of all RRT lodgements in 2013–14, making China the second most common country of origin of RRT applicants. The number of lodgements from applicants from China increased by 48% compared to 2012–13. The majority of lodgements received where the applicant claimed citizenship of China, 85%, was from applicants residing in New South Wales.

The RRT set-aside, or set-aside and remitted, the department’s primary decision in 10% of cases involving applicants from China in 2013–14. The RRT remitted three cases to the department on complementary protection grounds involving applicants from China in 2013–14, down from six cases remitted on these grounds in 2012–13.

Case Study: RRT China – no convention grounds – tax evasion – affirmed

The applicant claimed that he helped his parents with farm work and when his family did not have the funds to pay tax officials who came to collect money, there was an altercation and the applicant assaulted an official. He claimed that his family was beaten and he was arrested by the police, detained and tortured. He further claimed that when tax officers could not obtain money from his family they took household goods. The applicant claimed that he was unable to present paperwork relating to the taxation matter. He claimed that before he left the country he sent a complaint letter to the authorities and this became known to the tax official. The applicant came to Australia on a student visa and he claimed that he had paid tuition fees but he had worked and not studied.

The tribunal found the applicant was not truthful in his claims, and that there were inconsistencies in his evidence. The tribunal found that the applicant had money in the bank which contradicted his claim that the dispute arose because the family was unable to pay taxes. The tribunal considered it implausible that there was no paperwork related to demands for taxation payments, and that the tax officers took the applicant’s family household goods. The tribunal did not accept that the applicant assaulted a tax official or that the applicant was taken into custody, beaten, tortured and detained. The tribunal found the applicant had difficulty providing details of the complaint letter he claimed to have sent and was vague about the letter’s contents. The tribunal noted that the applicant did not pursue any study in Australia despite having prepaid the tuition fees, that he had preferred employment to study and waited until the expiry of his visa before seeking protection. The tribunal rejected the entirety of the applicant’s claims and found that he had fabricated his claims for the purpose of his protection visa application. Therefore, the tribunal was not satisfied that the applicant was a person to whom Australia had protection obligations under the Refugees Convention and Protocol. The tribunal was also not satisfied that the applicant was a person in respect of whom Australia had complementary protection obligations.

Lebanon

The number of lodgements received from applicants from Lebanon was consistent with 2012–13 levels and comprised 3% of all RRT lodgements in 2013–14. No applications from unauthorised maritime arrivals from Lebanon were received. The majority of applications for review, 75%, were lodged from applicants residing in New South Wales.

The RRT set-aside, or set-aside and remitted, the primary decision in 17% of cases involving applicants from Lebanon. The RRT remitted to the department on complementary protection grounds seven cases involving applicants from Lebanon in 2013–14. This compares to nil cases in 2012–13.

Case Study: RRT Lebanon – support for the Syrian President – Alawi Muslim – set-aside

The applicant had come to Australia to undertake postgraduate study, but this plan fell apart when his father was no longer able to provide financial support. This was because his father’s business had suffered due to the unrest in Tripoli. The applicant claimed to fear that he would suffer serious harm if he returned to Lebanon because of his Alawi religion and that he was known and identified as an Alawi in his social circles and elsewhere in Lebanon, and that he would never seek to hide or deny his Alawi faith. The applicant claimed that the crisis in Syria placed him at greater risk of harm as an Alawi Muslim, not only because of his religion but also because of his political views and his support for the Syrian President Bashar al Assad.

The tribunal found the applicant to be a credible and persuasive witness who did not seek to exaggerate or overstate the harm he feared he would suffer in Lebanon. The tribunal accepted his commitment to his religion, which formed his identity as an individual and as part of a prominent Alawi family. The tribunal noted the current sectarian violence in Tripoli as a result of the Syrian conflict meant that it could not confidently find that the applicant could return to Tripoli and live there in safety as an Alawi Muslim, either at the former family home or with his parents who temporarily live elsewhere in Lebanon. The tribunal considered that ensuring his safety would likely require the applicant to conceal his religious beliefs or otherwise modify his behaviour to avoid serious harm. The tribunal determined that in the applicant’s particular circumstances, the denial of a right to freely express his religious identity and beliefs constituted serious harm consistent with s.91R(1)(b). The tribunal found that despite the efforts of the authorities in Lebanon to intervene in fighting between Alawites and Sunnis, it could not confidently find that the applicant could obtain effective protection from the authorities and on this basis he could not safely relocate elsewhere in Lebanon. The tribunal was satisfied the applicant was a person in respect of whom Australia has protection obligations under the Refugees Convention and Protocol.

Timeliness

Cases are allocated to members in accordance with legislation and strategies put in place for the effective management of the tribunals’ caseload. Depending on available member capacity and lodgements, this may mean that not all cases can be quickly allocated to a member. Following allocation of a case, members are expected to promptly identify the relevant issues and the course of action necessary to enable the review to be conducted as effectively and efficiently as possible. Senior members manage their teams’ caseloads to achieve tribunal decision and timeliness targets, including by monitoring older and priority cases to minimise unnecessary delays, and managing member performance. Figure 6 displays the percentage of cases decided within the tribunals’ time standards over the past three years and Table 5 displays the average time taken (days) to decide for each decision type by financial year.

Figure 6 – Percentage of cases decided within time standards

| 2013–14 | 2012–13 | 2011–12 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average time taken to decision (days)* | |||

| Bridging visa (detention) refusals (MRT) | 6 | 6 | 7 |

| Visa cancellations (MRT) | 255 | 342 | 224 |

| All other MRT visa refusals | 377 | 421 | 461 |

| Protection visa refusals | 237 | 159 | 149 |

* Calendar days, other than for bridging (detention) cases, where working days are used. Time standards are as set out in the Migration Act and Migration Regulations or in the 2013–14 Portfolio Budget Statement. For MRT cases, time taken is calculated from date of lodgement. For RRT cases, time taken is calculated from the date the department’s documents are provided to the RRT. The average time from lodgement of an application for review to receipt of the department’s documents was 31 days for MRT cases and 10 days for RRT cases.

Some cases cannot be decided within the time standards. These include cases where hearings need to be rescheduled because of illness or because an interpreter is not available, cases where the applicant requests further time to comment or respond to information, cases where new information becomes available, and cases where information needs to be obtained from another body or agency.

The timeliness of reviews has been affected by large increases in lodgements in recent years. This was a factor again for the RRT in 2013–14, following a substantial increase in RRT lodgements during the year. MRT timeliness improved significantly in 2013–14.

The Principal Member reports every four months on the compliance of the RRT with the 90 day standard for protection visa reviews. These reports are provided to the Minister for tabling in Parliament. In 2013–14, only 16% of RRT cases were decided within 90 days; the average time to decision was 237 days. This is a decline from the average time to decision in 2012–13 of 159 days and reflects the prioritisation of RRT cases other than unauthorised maritime arrival cases required by a Ministerial Direction issued on 1 July 2013, in contrast to the tribunals’ prioritisation of unauthorised maritime cases in 2012–13.

In 2014-15, the tribunals will continue to seek increased productivity through member specialisation, maintaining the use of hearing lists for less complex cases, adjustments to decision writing and other measures designed to enhance efficiency. The tribunals will focus in particular on identifying efficiencies in the case allocations process in 2014-15.

Judicial review

For persons wishing to challenge a tribunal decision, two avenues of judicial review are available. One is to the Federal Circuit Court, and the other is to the High Court. Decision making under the Migration Act continues to be an area where the level of court scrutiny is very intense and where the same tribunal decision or the same legal point may be upheld or overturned at successive levels of appeal.

The applicant and the Minister are generally the parties to a judicial review of a tribunal decision. Although joined as a party to proceedings, the tribunals do not take an active role in litigation. As a matter of course, the tribunals enter a submitting appearance, consistent with the principle that an administrative tribunal should generally not be an active party in judicial proceedings challenging its decisions.

In 2013–14 the number of tribunal decisions taken to judicial review increased in comparison with previous years, reflecting the larger number of decisions made by the tribunals during 2013–14. However, the percentage of decisions taken to judicial review, while showing an increasing trend over recent years, remains broadly consistent.

Of all decisions made by the tribunals in 2013–14, only a small percentage (0.3% of MRT decisions and 0.8% of RRT decisions) have been set-aside or quashed by the courts. If a tribunal decision is set-aside or quashed, the court order is usually for the matter to be remitted to the tribunal to be reconsidered. In such cases the tribunal (which may be constituted by the same or a different member) must reconsider the case and make a fresh decision, taking into account the decision of the court and any further evidence or changed circumstances. In 28% of MRT cases and 31% of RRT cases reconsidered in 2013–14, the reconstituted tribunal made a decision favourable to the applicant.

Table 6 sets out judicial review applications and outcomes for the tribunal decisions made over the last three years. It displays the number of tribunal decisions made during the reporting period that have been the subject of a judicial review application, and the judicial review outcome for those cases.

Less than 1% of tribunal decisions made in 2013–14 have been set-aside or quashed by the courts

| MRT | RRT | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013–14 | 2012–13 | 2011–12 | 2013–14 | 2012–13 | 2011–12 | |

| Tribunal decisions | 24,729 | 15,590 | 8,011 | 3,585 | 3,757 | 2,804 |

| Court applications | 1,575 | 770 | 263 | 1,101 | 949 | 695 |

| % of tribunals decisions | 7.4% | 4.9% | 3.3% | 30.7% | 25.3% | 24.8% |

| Applications resolved | 517 | 675 | 259 | 237 | 720 | 687 |

| Decision upheld or otherwise resolved | 461 | 602 | 219 | 208 | 611 | 601 |

| Set-aside by consent or judgment | 56 | 73 | 40 | 29 | 109 | 86 |

| Set-aside decisions as % of judicial applications resolved | 10.8% | 10.8% | 15.4% | 12.2% | 15.1% | 12.5% |

| Set-aside decisions as % of decisions made | 0.3% | 0.5% | 0.5% | 0.8% | 2.9% | 3.1% |

The outcome of judicial review applications is reported on completion of all court appeals against a tribunal decision. Previous years’ figures are affected if a further court appeal is made against a case that was previously counted as completed.

Notable judicial decisions

Summaries of notable judicial decisions since 1 July 2013 are set out on the following pages. These decisions had an impact on the tribunals’ decision making or procedures, or on the operation of judicial review regarding tribunal decisions.

As there are restrictions on identifying applicants for protection visas, letter codes or reference numbers are used by the courts in these cases. Unless stated otherwise, references are to the Migration Act and Migration Regulations. The Minister is a party in most cases, and ‘MIBP’ and ‘MIMAC’ are used to identify the Minister in the abbreviated citations provided.

Time of tribunal decision

The RRT affirmed a decision of a delegate of the Minister not to grant the visa applicant a protection visa before the complementary protection provisions came into effect on 24 March 2012. The RRT sent a copy of its decision to the applicant and to the department. The copy of the decision sent to the applicant was not sent to his last residential address provided to the RRT in connection with the review and the RRT did not send a copy of its decision to the correct address until after the complementary protection provisions had come into effect. On appeal, the Full Federal Court held that the RRT application was not finally determined until such time as the RRT had notified both the applicant and the department in accordance with the Act. Therefore the application for review had not been ‘finally determined’ prior to 24 March 2012 and the RRT fell into jurisdictional error by failing to consider the complementary protection grounds. [MIMAC v SZRNY [2013] FCAFC 104]

A right to enter and reside in a country other than Australia

The applicants, who were Nepalese nationals, applied for protection visas. The RRT found that each of the visa applicants had a legally enforceable right to enter and reside in India arising from a Treaty between Nepal and India and affirmed the decisions of the delegate not to grant each applicant a protection visa. On appeal the Full Federal Court held that the meaning of the ‘right to enter and reside’ in section 36(3) of the Act did not refer to a legally enforceable right, and that it was sufficient to have a liberty, permission or privilege lawfully given. The Full Federal Court also observed that the terms of the Treaty in combination with the administrative arrangements for entry by Nepalese citizens at the Indian border may satisfy the test of ‘right to enter and reside’ for the purposes of section 36(3) of the Act. [MIMAC v SZRHU [2013] FCAFC 91]

The applicants, who were citizens of Burundi, applied for protection visas. In each case, the RRT determined that the applicants had a well-founded fear of persecution for a Convention reason in respect of Burundi. The RRT accepted that because Burundi was a member country of the East African Community (EAC), each applicant had a right to enter any other member countries of EAC and reside there for up to six months. However, the RRT found that this was not a ‘right to enter and reside’ within the meaning of section 36(3) of the Act because the applicants would have to leave the other EAC country within six months and the feared persecution would not cease within that period. The Minister appealed from the RRT decisions. On appeal, the Full Federal Court held that the RRT erred in finding that the temporary period of residence contemplated by section 36(3) must be commensurate with the period of time during which an applicant’s fear of persecution in his or her country of origin is likely to continue. [SZRTC v MIBP [2014] FCAFC 43]

Modification of conduct

The applicant applied for a protection visa on the basis that he feared persecution in Afghanistan because of his work as a truck driver transporting goods for foreign agencies and political opinion was imputed to him as a supporter of foreign agencies. The RRT did not accept that working as a truck driver was a core aspect of the applicant’s identity, belief or lifestyle which he should not be expected to modify or forego. The RRT found that if he returned to Afghanistan, the applicant would not be constrained to continue working as a truck driver and could work as a jeweler so that he was not obliged to travel to make a living. The Full Federal Court held that the RRT erred in failing to consider whether and why the applicant would change his occupation and work as a jeweler if he was returned to Afghanistan, and the threat which caused it. [MIBP v SZSCA [2013] FCAFC 155]

Reasonableness of refusal of request for adjournment

The applicant was seeking a skilled visa, which required that he achieved a requisite score in each test component (speaking, reading, writing and listening) of an International English Language Testing System (IELTS) test. At the tribunal hearing in November 2012, the MRT agreed to wait until close of business on 31 December 2012 to receive the results of the IELTS tests which the applicant had booked on 17 November 2012 and 1 December 2012, but said that it would not wait for further evidence after that date, as the applicant had made his visa application over two years before and had had many opportunities to sit several English language tests. On 1 January 2013, the applicant submitted IELTS test results which showed he had achieved the requisite scores in the December test in all components except ‘listening’. The applicant stated that he intended to apply for a re-marking of that test and hoped to get the required result after the re-marking. The MRT refused to grant additional time and proceeded to make its decision on 11 January 2013. The Full Federal Court held that the MRT’s refusal to grant additional time was legally unreasonable as the MRT had not given the adjournment request any independent, active consideration and did not ask itself how long the re-mark would take. [MIBP v Singh [2014] FCAFC 1]

Multi-Applicant Hearing List process and refusal of request for adjournment

The applicant applied for a skilled visa in March 2011. A delegate of the Minister refused to grant the visa as the applicant did not have evidence of competent English, which required that he achieved a requisite score in an IELTS test. On review, the MRT invited the applicant to a hearing. The hearing was conducted where eight or nine other applicants were present in the same hearing room as those matters were also listed for hearing before the MRT at the same time. The applicant sought additional time to sit an IELTS test that he had booked in May 2013 on the basis that he was recovering from a back injury and had not started studying until after that. The MRT refused to grant additional time because the applicant had made his visa application over two years before, had had several opportunities to sit the IELTS test and had continued to work after his back injury. The MRT affirmed the decision on the basis that he did not have evidence of competent English. The Federal Circuit Court held that it was open for the MRT, a busy tribunal, to conduct running lists with a number of applicants in the hearing room at any one time, in order to deal with its substantial workload. It held that nothing was unfair or unreasonable in the MRT declining the applicant’s request for extra time. [Uddin v MIMAC [2013] FCCA 906]

False and misleading information

The applicant had applied for a skilled visa. The applicant had provided an IELTS test result form with her visa application that recorded higher scores than she had actually received. The applicant claimed that she did not know there was anything wrong with the IELTS test result form at the time she submitted it and that she was not personally involved in or aware of the deception. The MRT affirmed the decision not to grant the applicant the visa because it found that the IELTS test result form submitted by the applicant contained information that was false or misleading in a material particular and, therefore, she did not satisfy public interest criterion (PIC) 4020. The MRT found that the requirements of PIC 4020 applied regardless of whether the test result form had been provided unknowingly or unwittingly, or how it came into existence or came to be given. The Full Federal Court held that this was correct. The Court held that there must be some element of knowledge or intention on somebody’s part and an element of fraud or deception to attract the operation of PIC 4020. However, it was not necessary that an applicant know of, or be directly involved in, any falsehood for PIC 4020 to be engaged. [Trivedi v MIBP [2014] FCAFC 42]

Social justice and equity

The tribunals’ service charter expresses the commitment to providing a quality service to stakeholders. The new service charter was published on the tribunals’ website in March 2014 and incorporates feedback received from members, staff and stakeholders. It sets out general standards for client service covering day-to-day contact with the tribunals, responding to correspondence, arrangements for attending hearings, the use of interpreters, providing information that enables effective engagement in the review process, and uses language that is clear and understood. The service charter also outlines the process for providing feedback or making a complaint. Feedback assists the tribunals to understand what is working well and where improvements can be made. The service charter is available in Arabic, Chinese, Dari, English, Farsi, Hindi, Korean, Punjabi, Tamil, Urdu and Vietnamese.

Table 7 sets out the tribunals’ performance during the year against service standards contained in the new service charter.

| Service standard | Report against standard for 2013–14 | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Be polite, respectful, courteous and prompt when we deal with you | All new members and staff attended induction training emphasising the importance of providing quality service to clients. | Achieved |

| 2. Use language that is clear and easily understood | Clear English is used in correspondence and forms. Staff use professional interpreters to communicate with clients from non-English speaking backgrounds. There is a language register listing staff available to speak to applicants in their language, where appropriate. The tribunals book interpreters for hearings whenever they are requested by applicants and wherever possible accredited interpreters are used in hearings. Interpreters were used in 65% of hearings held (57% MRT and 85% RRT). The tribunals employ staff from diverse backgrounds who speak more than 20 languages. | Achieved |

| 3. Acknowledge applications for review in writing within two working days | An acknowledgement letter was sent within two working days of lodgement in 55% of cases. | 55% |

| 4. Include a contact name and telephone number on all our correspondence | All letters include a contact name and telephone number. | Achieved |

| 5. Help you to understand our procedures | The tribunals provide applicants with information about tribunal procedures at several stages during the review process. The website includes a significant amount of information, including procedures and guidelines, forms and factsheets and frequently asked questions. Case officers are available in the New South Wales and Victoria registry to explain procedures over the counter or the telephone. The tribunals have an email enquiry address and an online enquiry form on the website that applicants can use to seek general information about procedures. | Achieved |

| 6. Provide information about where you can get advice and assistance | The website, service charter and application forms provide information about where applicants can get advice and assistance. Factsheet MR2: Immigration Assistance notifies applicants of organisations and individuals who can provide them with immigration assistance. The application forms R1, M1 and M2 explain in 28 community languages how applicants may contact the Translating and Interpreting Service (TIS). | Achieved |

| 7. Provide information so that you can engage effectively in the review process | The tribunals provide applicants with information about tribunal procedures at several stages during the review process. The website includes a significant amount of information, including procedures and guidelines, forms and factsheets and frequently asked questions. The Stakeholder Engagement Plan for 2012–14 sets out how the tribunals will engage with stakeholders and the engagement activities planned for 2012–14 and beyond. Community liaison meetings were held twice during 2013–14 in Adelaide, Brisbane, Melbourne, Perth and Sydney. The tribunals have a feedback and complaints process outlined in the service charter and on the website. | Achieved |

| 8. Provide you with advance notice of the time and place of the hearing, if we invite you to a hearing | The Migration Regulations prescribe the periods for notifying applicants of MRT and RRT hearings. The tribunals invite applicants to hearings in accordance with the time frames referred to in the Migration Regulations. | Achieved |

| 9. Attempt to assist you if you have difficulty understanding or participating in the review process due to age or a physical, mental, psychological or intellectual condition, disability or frailty or for social or cultural reasons | The tribunals employ a range of strategies to assist applicants who have difficulty understanding or participating in the review process. All offices are wheelchair accessible and hearing loops are available for use in hearing rooms. Whenever possible, requests for interpreters of a particular gender, dialect, ethnicity or religion are met. Hearings can be held by video conference. A national enquiry number 1300 361 969 is available from anywhere in Australia (calls are charged at the cost of a local call, more from mobile telephones). The tribunals have guidelines that address gender issues and the needs of vulnerable persons during the review process. | Achieved |

| 10. Provide reasons for our decisions | In most cases (except where a case is withdrawn or where the tribunals are notified of the applicant’s death), a written record of decision and the reasons for decision are provided to the applicant and to the department. | Achieved |

| 11. Publish guidelines relating to the priority we give to particular cases | Guidelines for the priority to be given to particular cases are published in the annual constitution and prioritisation policy, which is available on the website. | Achieved |

| 12. Publish the time standards within which we aim to complete reviews | Time standards are available on the tribunals’ website. | Achieved |

| 13. Abide by the Australian Public Service (APS) Values and Code of Conduct (staff) available at www.apsc.gov.au | New staff attend induction training, which includes training on the APS Values and the Code of Conduct. Ongoing staff complete refresher training at regular intervals. | Achieved |

| 14. Abide by the Member Code of Conduct (members) available on the website | All new members attend induction training, which includes the Member Code of Conduct. All members complete annual conflict of interest declaration forms and undergo performance reviews. | Achieved |

| 15. Publish information on caseload and tribunal performance | Information about caseload and performance in the current and previous financial years is published on the website under ‘statistics’. Further statistics, including those on the judicial review of tribunal decisions, are available in annual reports. | Achieved |

A high proportion of applicants have a language other than English as their first language. Clear language in letters and forms, and the availability of staff to assist applicants, are important to ensuring that applicants understand their rights and tribunal procedures and processes and can engage effectively in the review process.

The tribunal website is a significant information resource for applicants and others interested in the work of the tribunals. The publications and forms available on the website are regularly reviewed to ensure that information and advice are up-to-date and readily understood by clients.

The service charter is available on the website, along with the Strategic Plan, the Member Code of Conduct, the Interpreters’ Handbook and Principal Member directions as to the conduct of reviews. The ‘representatives’ webpage supports representatives by bringing together the most commonly used resources and information. A ‘frequently asked questions’ page, arranged by topic, answers questions most commonly asked by applicants and representatives.

The tribunals have offices in Melbourne and Sydney which are open between 8.30 am and 5.00 pm on working days. The tribunals have an arrangement with the AAT for counter services and hearings at AAT offices in Adelaide, Brisbane and Perth. The tribunals also have a national enquiry number (1300 361 969) available from anywhere in Australia (calls are charged at the cost of a local call, more from mobile telephones). Persons who need the assistance of an interpreter can contact the Translating and Interpreting Service on 131 450 for the cost of a local call.

The tribunals have a Reconciliation Action Plan, an Agency Multicultural Plan and a Workplace Diversity Program. Further information about these strategies and plans is set out in Part 4.

Complaints

The service charter sets out the standards of service that clients can expect. It also sets out how clients can comment on or complain about the services provided by the tribunals. The service charter is available on the ‘conduct of reviews’ page on the website and in ten community languages.

Most issues or concerns that arise in the normal course of business are handled informally at the local level, and do not result in a formal complaint. Formal complaints are handled in accordance with the tribunals’ complaints policy. Formal complaints are always in writing. Complaints about tribunal members are dealt with by the Principal Member. Complaints about staff or other matters are dealt with by the Registrar.

A person who is dissatisfied with how the tribunals have dealt with a matter or with the standard of service they have received, and who has not been able to resolve this by contacting the office or the officer dealing with their case, can forward a written complaint marked ‘confidential’ to the Complaints Officer.

Alternatively, a person can make a complaint to the Commonwealth Ombudsman, although the Ombudsman will not usually investigate a complaint that has not first been raised with the relevant agency.

The tribunals will acknowledge receipt of a complaint within five working days and aim to provide a final response within 20 working days of receipt of the complaint. The length of time before a final response depends on the extent of investigation which is necessary. If more time is required, because of the complexity of the complaint or the need to consult with other persons before providing a response, the tribunal will advise the complainant of progress in handling the complaint.

If a complaint is upheld, possible responses include an apology, a change to practice and procedure, or consideration of additional training and development for tribunal personnel.

During 2013–14, the tribunals received a total of 56 complaints. Table 8 shows the number of formal complaints made over the last three years.

| 2013–14 | 2012–13 | 2011–12 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Complaints lodged | 56 | 33 | 19 |

| Cases decided | 24,729 | 19,347 | 10,815 |

| Complaints per 1,000 cases | <3 | <2 | <2 |

Of the complaints made in 2013–14, 33 related to member conduct, two related to staff conduct, four related to member and staff conduct, and 17 related to tribunal policy and timeliness.

The tribunals provided substantive responses to 55 of the 56 complaints, responding to 35 of those complaints within 20 working days. One complaint was unresolved at the time of this report.

Less than three complaints were received per 1,000 cases decided

Following investigation, the tribunal formed the view that six of the complaints made during the year related to matters which could have been handled more appropriately.

Table 9 sets out the complaints made to the Commonwealth Ombudsman over the last three years and the outcomes of the complaints resolved.

| 2013–14 | 2012–13 | 2011–12 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| New complaints | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Complaints resolved | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Administrative deficiency found | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Migration agents

More than 59% of applicants were represented in relation to their review application in 2013–14. With limited exceptions, a person acting as a representative is required to be a registered migration agent. Registered migration agents are required to conduct themselves in accordance with a code of conduct. The tribunals referred three matters to the Office of the Migration Agents Registration Authority (OMARA) during 2013–14 regarding the conduct of migration agents. OMARA is responsible for the registration of migration agents, monitoring the conduct of registered migration agents, investigating complaints and taking disciplinary action against registered migration agents who breach the code of conduct or behave in an unprofessional or unethical way.

Community and interagency liaison

The tribunals maintain regular engagement with a number of bodies with an interest in refugee and migration law, tribunal outcomes and merits review. The Stakeholder Engagement Statement outlines the principles for engaging with clients and stakeholders, and strategies to support and improve communication and services.

Twice-yearly community liaison meetings are held in Melbourne, Sydney, Brisbane, Adelaide and Perth to exchange information with key stakeholders. At community liaison meetings, updates are provided on legislative and corporate developments and attendees can raise matters that arise out of their dealings with the tribunals. The meetings are attended by representatives of migration and refugee advocacy groups, legal and migration agent associations, human rights bodies, the department and other government agencies.

The tribunals hold ‘open days’ or public information sessions each year. In 2014 MRT information sessions were held in Brisbane, Melbourne and Sydney during Law Week in May, and RRT information sessions were held in Melbourne, and Sydney during Refugee Week in June. Information sessions involve a demonstration hearing and presentations on the tribunals’ processes and caseloads. These events are an opportunity for the public to get a better understanding of tribunal operations. There was a strong turnout and positive feedback from those who attended.

MRT Open Day held in the Victorian Registry. The presentation included a staged MRT hearing demonstrating the hearing process and use of interpreters.

Regular meetings are held with the department, the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade and the AAT. Agreements between the tribunals and these organisations reflect the statutory and operational relationships between the agencies.

Members and staff have continued to be active participants in several bodies, including the national and state chapters of the Council of Australasian Tribunals, the Australasian Institute of Judicial Administration, the Australian Institute of Administrative Law and the International Association of Refugee Law Judges.

Members and staff presented on the work of the tribunals at several events in 2013–14. In September 2013, the Principal Member spoke at the Migration Alliance Annual Conference on strengthening relationships between registered migration agents and the MRT. In March 2014, the Principal Member gave a presentation on fair, just, economical, informal and quick reviews at the Law Council of Australia’s 2014 Immigration Law Conference held in Sydney. In April 2014, the Deputy Principal Member gave a presentation on business visa issues at a Migration Institute of Australia continuing professional development workshop in Perth. Significant speeches and presentations given by members and staff are published on the website.

130 people attended community liaison meetings in 2013–14

Major reviews

No major reviews were undertaken in relation to the tribunals during 2013–14.

Capability reviews

No capability reviews were undertaken for the tribunals during 2013–14.

Significant changes in the nature of functions or services

Amalgamation of the tribunals

The 2014-15 Budget includes a measure to amalgamate the tribunals with three other Commonwealth merits bodies: the Administrative Appeals Tribunal (AAT), Social Security Appeals Tribunal (SSAT), and the Classification Review Board (CRB). The formal amalgamation is proposed to come into effect on 1 July 2015 with legislation introduced and passed during 2014–15. The reforms are expected to generate efficiencies and savings through shared financial, human resources, information technology and governance arrangements.

Functus officio legislation

The Migration Amendment Bill 2013, which specifies when the tribunals are functus officio, received Royal Assent on 27 May 2014. The Act amends the Migration Act 1958 to clarify that a decision (other than an oral decision) is taken to be made by the making of the written statement on the date and time the written statement is made. The date and time the decision statement is made must be written on the decision statement. An oral decision is taken to be made, and notified to the applicant, on the date and time the decision is given orally. The date and time the decision is given orally must also be written on the decision statement.

Developments since the end of the year

None.

![Australian Government - Migration Review Tribunal - Refugee Review Tribunal [header logo image]](img/header/img-hdr-logo.jpg)