Part 3 – Performance report

Contents

The tribunals contributed to Australia’s migration and refugee programs during the year through the provision of quality and timely reviews of decisions.

Performance framework

The tribunals operated in a high volume decision-making environment where the case law and legislation are complex and technical. The tribunals had identical statutory objectives, set out in sections 353 and 420 of the Migration Act:

The tribunal shall, in carrying out its functions under this Act, pursue the objective of providing a mechanism of review that is fair, just, economical, informal and quick.

The key strategic priorities were to meet these statutory objectives through the delivery of consistent, high quality reviews, and timely and lawful decisions.

Each review had to be conducted in a way that ensured, as far as practicable, that the applicant understood the issues and had a fair opportunity to comment on or respond to any matters which might have led to an adverse outcome.

The tribunals also aimed to meet government and community expectations and to have effective working relationships with stakeholders. These priorities were reflected in the tribunals’ strategic plan.

For 2014–15, one outcome was specified in the Portfolio Budget Statement:

To provide correct and preferable decisions for visa applicants and sponsors through independent, fair, just, economical, informal and quick merits reviews of migration and refugee decisions.

The tribunals had one program contributing to this outcome, which was:

Final independent merits review of decisions concerning refugee status and the refusal or cancellation of migration and refugee visas.

Table 2 summarises performance against the program deliverables and key performance indicators that were set out in the Portfolio Budget Statement.

| Measure | Result |

|---|---|

| Key performance indicators | |

| Less than 5% of tribunal decisions set-aside by judicial review | 0.5% of MRT and 0.7% of RRT decisions made in 2014–15 were set-aside by judicial review. |

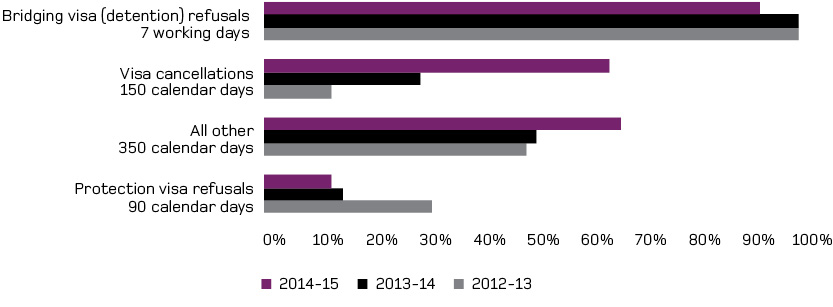

| 70% of cases decided within time standards | 89% of bridging visa (detention) refusals were decided within seven working days. 12% of protection visa refusals were decided within 90 calendar days. 62% of visa cancellations were decided within 150 calendar days. 64% of all other visa refusals were decided within 350 days. |

| Less than five complaints per 1,000 cases decided | Less than four complaints per 1,000 cases decided (69 complaints). |

| At least 3,000 decisions published | 3,049 decisions published. |

Lodgements declined by 17% in 2014–15, contributing to an 18% reduction in the on-hand caseload to fewer than 14,000 cases. The positive clearance rate of cases significantly improved the timeliness of MRT reviews of visa refusals from 364 average calendar days from lodgement in 2013–14 to 289 average calendar days in 2014–15.

Financial performance

The MRT and the RRT were prescribed as a single non-corporate entity, the ‘Migration Review Tribunal and Refugee Review Tribunal’ for the purposes of the PGPA Act. The tribunals were funded based on a model which took into account the number of reviews finalised. The tribunals’ base funding in 2014–15 covered an amount to finalise 18,000 reviews. This funding was adjusted at a marginal rate per review based on actual reviews finalised whether above or below that number. 21,567 reviews were finalised in 2014–15 and the revenue as set out below has taken into account an adjustment to appropriation based on the actual number of reviews finalised.

The tribunals continued to record a strong financial performance in 2014–15, despite the challenges posed by increased activity and complex operational demands. The tribunals managed ongoing business as well as whole-of-government initiatives and changes efficiently and cost-effectively. The 2014-15 financial statements reported revenues from ordinary activities of $73.59 million and expenditure of $69.55 million, resulting in a net surplus of $5.08 million and depreciation worth $3.55 million.

The tribunals administered application fees on behalf of the government. Details of administered revenue are set out in the financial statements.

The financial statements for 2014–15, which are set out in part 5, have been audited by the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) and received an unqualified audit opinion.

Overview of caseload

MRT and RRT caseload

The tribunals received 18,534 lodgements, finalised 21,567 cases and had 13,937 cases on hand at the end of the year. Table 3 provides an overview of the tribunals’ caseload over the past three years.

| 2014–15 | 2013–14 | 2012–13 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MRT | |||

| On hand at start of year | 11,719 | 17,437 | 16,863 |

| Lodged | 14,398 | 15,426 | 16,164 |

| Decided | 16,584 | 21,144 | 15,590 |

| On hand at end of year | 9,533 | 11,719 | 17,437 |

| RRT | |||

| On hand at start of year | 5,251 | 1,973 | 1,501 |

| Lodged | 4,136 | 6,863 | 4,229 |

| Decided | 4,983 | 3,585 | 3,757 |

| On hand at end of year | 4,404 | 5,251 | 1,973 |

| TOTAL MRT AND RRT | |||

| On hand at start of year | 16,970 | 19,410 | 18,364 |

| Lodged | 18,534 | 22,289 | 20,393 |

| Decided | 21,567 | 24,729 | 19,347 |

| On-hand at end of year | 13,937 | 16,970 | 19,410 |

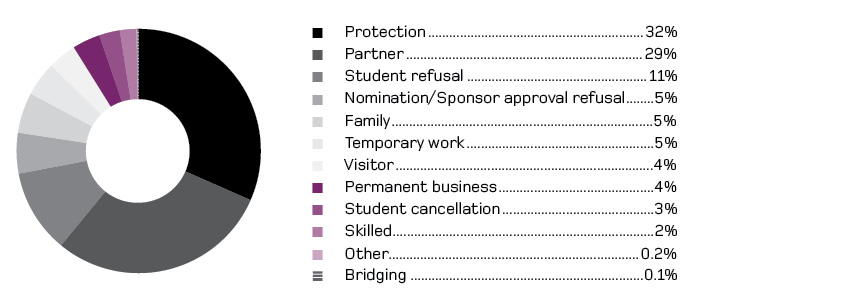

Figure 1 displays each case category as a percentage of the caseload on hand at 30 June 2015.

Figure 1 – MRT and RRT cases on hand as at 30 June 2015

Lodgements

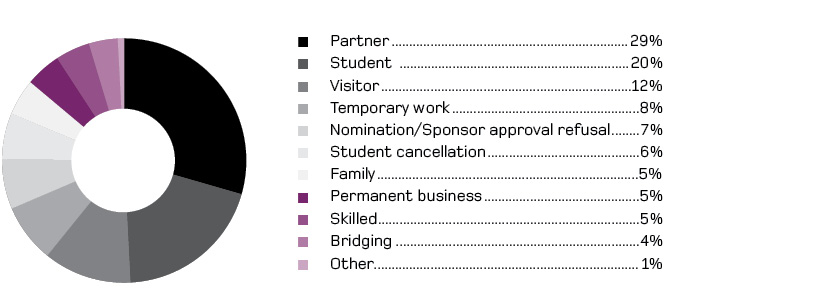

The MRT had jurisdiction to review a wide range of visa, sponsorship and other decisions for migration and temporary entry visas. In 2014–15, the MRT received 14,398 lodgements. There was a significant increase in partner lodgements as well as increases in student cancellation and bridging visa review lodgements. Significant decreases occurred in skilled and permanent business lodgements. Figure 2 provides an overview of MRT lodgements by case category.

Figure 2 – MRT lodgements by case category

The MRT’s jurisdiction to review decisions about visas applied for outside Australia depended on whether there was a requirement for an Australian sponsor or for a close relative to be identified in the application. These cases were mainly in the permanent business, temporary work, visitor, partner and family categories. In 2014–15, approximately 21% of applications for review of visa refusal decisions by the MRT related to persons outside Australia seeking a visa.

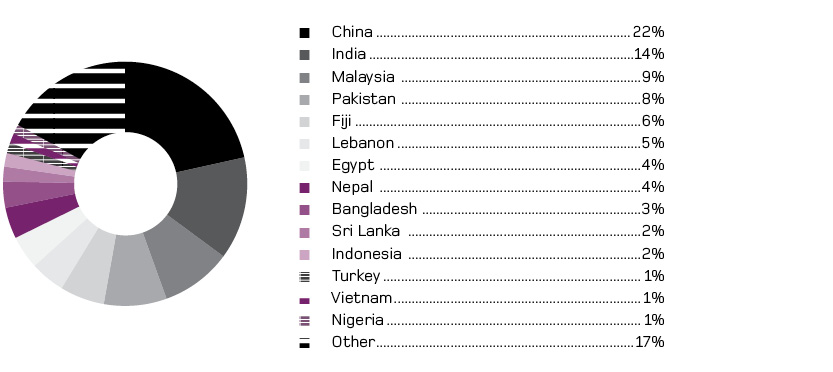

The RRT had jurisdiction to review decisions to refuse or cancel protection visas. In 2014–15, the RRT received 4,136 lodgements, a decline of 40% compared to 2013–14. Unlike the previous year, more than 80% of cases were lodged by applicants other than unauthorised maritime arrivals. The decline in lodgements was in part a result of a 79% decrease in applications from unauthorised maritime arrivals with 648 cases lodged in 2014–15. Applications for review to the RRT were received from persons from 91 different countries. Nationals of five countries – China, India, Malaysia, Pakistan and Bangladesh – comprised more than 50% of all RRT lodgements. Figure 3 provides an overview of all lodgements received by the RRT by country of origin.

Figure 3 – RRT lodgements by country

The largest growth in RRT lodgements by country of origin was by nationals from Malaysia (327), an increase of 227%, comprised solely of applicants other than unauthorised maritime arrivals. Unauthorised maritime arrival review applications by nationals from Bangladesh (292) increased by 92%, while applications by nationals from Afghanistan, Sri Lanka and Iran significantly decreased compared to 2013–14.

There were 22 review lodgements as a result of the cancellation of a protection visa by the department in 2014–15 compared to four lodgements in 2013–14. This was a reflection of the department’s increased focus on the integrity of the protection visa program.

More than 80% of RRT cases lodged were from applicants other than unauthorised maritime arrivals

Figures 4 and 5 below provide an overview of RRT lodgements by country of origin for unauthorised maritime arrivals and all other RRT applicants (excluding unauthorised maritime arrivals).

Figure 4 – RRT lodgements by country for unauthorised maritime arrivals

Figure 5 – RRT lodgements by country for applicants other than unauthorised maritime arrivals

Applicants to the tribunals were located in the larger metropolitan areas of Australia. The proportion of applicants to the tribunals who resided in New South Wales was 39%. This was followed by 32% of applicants who resided in Victoria, 11% in Queensland, 10% in Western Australia, 4% in South Australia, 1% each in the Australian Capital Territory and in the Northern Territory, and less than 0.5% in Tasmania. Overall the location of applicants to the tribunals remained steady compared to 2013–14.

The tribunals received a high proportion of review applications via an online lodgement facility in 2014–15. Online lodgements accounted for 66% of all lodgements. Online lodgements were particularly high for the nomination/sponsor approval (86%), temporary work (81%), student cancellation (78%) and student refusal (76%) caseloads as a percentage of all lodgement methods for each case category.

Cases involving applicants in immigration detention comprised 4% of applications received in 2014–15.

Conduct of reviews

The proceedings of the tribunals were inquisitorial and did not take the form of litigation between parties. The review was an inquiry in which the member identified the issues or criteria in dispute, initiated investigations or inquiries to supplement evidence provided by the applicant and the department and ensured procedural momentum. At the same time, the member had to maintain an open and impartial mind.

In 2014–15, there were 15,993 MRT hearings (including cases allocated to a hearing list) and 5,080 RRT hearings arranged. There were 10,550 MRT and 3,494 RRT cases with a hearing held that were completed or adjourned. The remaining hearings were postponed, rescheduled or did not proceed as the applicant did not attend.

Cases where no hearing was arranged included those where a decision favourable to the applicant was made or the applicant withdrew prior to a hearing being arranged. Favourable decisions were made without the requirement for a hearing in 6% of MRT cases and in 1% of RRT cases1.

Video links to applicants were used in 14% of MRT hearings and telephone in 8% of MRT hearings. The average duration of MRT hearings was 65 minutes. Video links were used in 18% of RRT hearings. The average duration of RRT hearings was 144 minutes. Two or more hearings were held in 3% of MRT cases and 6% of RRT cases.

Hearing lists generated case processing efficiencies and reduced the size of the student and skilled caseloads in 2014–15. They enabled a number of cases to be heard by the presiding member consecutively and were open to the public. In 2014–15, there were 3,991 cases listed in 1,126 hearing lists. Of these, 2,312 cases had a hearing held and the average hearing duration was 31 minutes. Hearings held included on hearing lists made up 22% of all MRT hearings completed.

1 Excludes 1,198 RRT cases, all of which were remitted to the department for reconsideration following the disallowance of clause 866.222 of Schedule 2 to the Migration Regulations 1994.

Interpreters

In 2014–15, interpreters were required for 59% of MRT hearings and 90% of RRT hearings equating to over 8,450 hearings. Interpreters were required in approximately 92 languages and dialects.

Interpreters in 92 languages and dialects were used in tribunal hearings

High quality interpreting services are fundamental to the work of the tribunals. Over the years the tribunals’ Interpreter Advisory Group (IAG), a national committee comprising members and staff, has worked to uphold best-practice interpreting at hearings.

The updated Interpreters’ Handbook provided comprehensive guidance for interpreters who worked in the tribunals as well as others involved in the review process.

Outcomes of review

In most cases a written statement of decision and reasons was prepared and provided to both the applicant and the department. From April 2015, a legislative amendment permitted the tribunals to give oral reasons, with written reasons on request, and introduced a power to dismiss an application if the applicant failed to appear at a scheduled hearing. Oral decisions were given in 2% of all finalised reviews in 2014–15.

The MRT set-aside, or set-aside and remitted, the primary decision in 33% of cases decided and affirmed the primary decision in 47% of cases decided. The remaining cases were either withdrawn by the applicant or were cases where the tribunal decided it had no jurisdiction to conduct the review. The MRT set-aside rate in 2014–15 increased slightly compared to the rate of 30% in 2013–14.

The RRT remitted the primary decision in 21% of cases decided and affirmed the primary decision in 72% of cases decided. The remaining cases were either withdrawn by the applicant or were cases where the tribunal decided it had no jurisdiction to conduct the review. The RRT remit rate in 2014–15 was consistent with the rate in 2013–14.

Most RRT remittals were on the basis that the applicant was a refugee. There were also 86 cases remitted with a direction that the applicant met the complementary protection criterion.

The fact that a decision was set-aside by the tribunal was not necessarily a reflection on the quality of the primary decision, which may have been correct and reasonable based on the information available at the time of the decision. Table 4 below provides an overview of the outcomes of review for the past three financial years.

| 2014–15 | 2013–14 | 2012–13 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MRT | |||

| Primary decision set-aside or remitted | 5,551 | 6,319 | 4,514 |

| Primary decision affirmed | 7,735 | 10,668 | 7,121 |

| Application withdrawn by applicant | 1,996 | 3,206 | 2,661 |

| No jurisdiction to review* | 1,302 | 951 | 1,294 |

| Total | 16,584 | 21,144 | 15,590 |

| RRT | |||

| Primary decision set-aside or remitted | 790 | 779 | 1,372 |

| Primary decision affirmed | 2,721 | 2,591 | 2,205 |

| Application withdrawn by applicant | 152 | 145 | 86 |

| No jurisdiction to review* | 122 | 70 | 94 |

| Total** | 4,983 | 3,585 | 3,757 |

* ‘No jurisdiction’ decisions included applications not made within the prescribed time limit, not made in respect of reviewable decisions or not made by a person with standing to apply for review.

** Total includes 1,198 RRT cases, all of which were remitted to the department for reconsideration following the disallowance of clause 866.222 of Schedule 2 to the Migration Regulations 1994.

Applications for review typically addressed the issues identified by the primary decision maker by providing submissions and further evidence to the tribunal. By the time of the tribunal’s decision, there was often considerable additional information before the tribunal. There may also have been court judgments or legislative changes that affected the outcome of the review.

Representation was most commonly by a registered migration agent. Applicants were represented in 68% of cases decided. In cases where applicants were represented, the set-aside rate was higher than for unrepresented applicants. The difference was more notable for RRT cases, where the set-aside rate was 27% for represented applicants and 9% for unrepresented applicants. Unrepresented applicants may not have sought advice on their prospects of success before applying for review or may have applied despite obtaining advice that the prospects of success were low. For the MRT, there was a smaller difference in outcome for unrepresented applicants. The set-aside rate was 36% for represented applicants and 28% for unrepresented applicants.

33% of MRT and 21% of RRT cases were decided in favour of the applicant

A total of 261 cases (approximately 1% of the cases decided) were referred to the department for consideration under the Minister’s intervention guidelines. These cases raised humanitarian or compassionate circumstances that members considered should be drawn to the attention of the Minister.

Timeliness

Cases were allocated to members in accordance with legislation, Ministerial Directions and caseload management strategies. Depending on available member capacity and lodgements, this may have meant that not all cases could be quickly allocated to a member. Following allocation of a case, members were expected to promptly identify the relevant issues and the course of action necessary to enable the review to be conducted as effectively and efficiently as possible. Senior members managed their teams’ caseloads to achieve tribunal decision and timeliness targets, including by monitoring older and priority cases to minimise unnecessary delays, and managing member performance. Figure 6 displays the percentage of cases decided within the tribunals’ time standards over the past three years and Table 5 displays the average time taken (days) to decide for each decision type by financial year.

Figure 6 – Percentage of cases decided within time standards

| 2014–15 | 2013–14 | 2012–13 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average time taken to decision (days)* | |||

| Bridging visa (detention) refusals (MRT) | 7 | 6 | 6 |

| Visa cancellations (MRT) | 151 | 255 | 342 |

| All other MRT visa refusals | 307 | 377 | 421 |

| Protection visa refusals | 264 | 237 | 159 |

* Calendar days, other than for bridging (detention) cases, where working days were used. Time standards were as set out in the Migration Act and Migration Regulations, or in the 201–15 Portfolio Budget Statement. For MRT cases, time taken was calculated from date of lodgement. For RRT cases, time taken was calculated from the date the department’s documents were provided to the RRT. The average time from lodgement of an application for review to receipt of the department’s documents was 30 days for MRT cases and 7 days for RRT cases.

Cases that could not be decided within timeframes included instances where hearings needed to be rescheduled because of illness or because an interpreter was not available, cases where the applicant requested further time to comment or respond to information, cases where new information became available, and cases where information needed to be obtained from another body or agency.

The timeliness of MRT reviews significantly improved in 2014–15. The average processing time for visa cancellations reduced to less than six months and improved to around ten months for all other MRT visa refusals. RRT reviews took around nine months on average to finalise. Their timeliness was impacted by the lifting of a Ministerial Direction which then enabled the tribunals to allocate and finalise a large quantity of older unauthorised maritime arrival cases that could not previously be prioritised under that Direction. The requirement for the Principal Member to report every four months on the compliance of the RRT with the 90 day time standard for protection visa reviews ended following changes to the Migration Act from 16 December 2014.

In 2015–16 use will continue to be made of hearing lists for less complex cases, member specialisation and other measures designed to enhance efficiency. The introduction of a secure portal for applicants to attach additional documents to their electronic case file at any time will promote further efficiencies in the review process. This will complement the high take-up rate of electronic communication between applicants and the tribunals in 2014–15.

Judicial review

For persons wishing to challenge a RRT or MRT decision, two avenues of judicial review were available. One was to the Federal Circuit Court, and the other was to the High Court. Decision making under the Migration Act continued to be an area where the level of court scrutiny was very intense and where the same tribunal decision or the same legal point may be upheld or overturned at successive levels of appeal.

The applicant and the Minister were generally the parties to a judicial review of a RRT or MRT decision. Although joined as a party to proceedings, the tribunals did not take an active role in litigation. As a matter of course, the tribunals entered a submitting appearance, consistent with the principle that an administrative tribunal should generally not be an active party in judicial proceedings challenging its decisions.

In 2014–15 the actual number of MRT and RRT decisions taken to judicial review increased in comparison with previous years, reflecting the larger number of decisions made by the tribunals during the year. The percentage of MRT decisions taken to judicial review also increased from 2013–14, although the trend was not replicated for the RRT.

Less than 1% of tribunal decisions made in 2014–15 were set-aside or quashed by the courts

Of the decisions made by the MRT and RRT in 2014–15, only a very small percentage (0.5% of MRT decisions and 0.7% of RRT decisions) were set-aside or quashed by the courts. If a tribunal decision was set-aside or quashed, the court order was usually for the matter to be remitted to the tribunal to be reconsidered. In 37% of MRT cases and 37.5% of RRT cases reconsidered in 2014–15, the reconstituted tribunal made a decision favourable to the applicant.

Table 6 sets out judicial review applications and outcomes for the MRT and RRT decisions made over the last three years. It displays the number of tribunal decisions made during the reporting period that have been the subject of a judicial review application, and the judicial review outcome for those cases.

| MRT | RRT | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014–15 | 2013–14 | 2012–13 | 2014–15 | 2013–14 | 2012–13 | |

| Tribunal decisions | 16,584 | 21,144 | 15,590 | 4983 | 3,585 | 3,757 |

| Court applications | 1,835 | 1,715 | 776 | 1,489 | 1,283 | 971 |

| % of tribunals decisions | 11.1% | 8.1% | 5% | 29.9% | 35.8% | 25.8% |

| Applications resolved | 507 | 1,414 | 760 | 265 | 827 | 889 |

| Decision upheld or otherwise resolved | 419 | 1,240 | 673 | 228 | 707 | 736 |

| Set-aside by consent or judgment | 88 | 174 | 87 | 37 | 120 | 153 |

| Set-aside decisions as % of judicial applications resolved | 17.4% | 12.3% | 11.4% | 14% | 14.5% | 17.2% |

| Set-aside decisions as % of decisions made | 0.5% | 0.8% | 0.6% | 0.7% | 3.3% | 4.1% |

The outcome of judicial review applications is reported on completion of all court appeals against a tribunal decision. Previous years’ figures are affected if a further court appeal is made against a case that was previously counted as completed.

Notable judicial decisions

Summaries of notable judicial decisions from 2014–15 that have had an impact on the tribunals’ decision making or procedures, or on the operation of judicial review regarding tribunal decisions, are set out below.

As there are restrictions on identifying applicants for protection visas, pseudonyms are used by the courts in these cases. Unless stated otherwise, references are to the Migration Act and Migration Regulations. The Minister is a party in most cases, and ‘MIBP’ is used to identify the Minister in the abbreviated citations provided.

Threat to liberty

The respondent, an Iranian national, claimed to fear he would suffer ‘serious harm’ under section 91R(2)(a) of the Act, in the form of temporary detention. An Independent Merits Reviewer (IMR) accepted the respondent would be detained for short periods, but without more, this did not amount to serious harm and persecution. The High Court, setting aside the decision of the Full Federal Court that had quashed the IMR decision, held that the question of whether a risk of loss of liberty constituted serious harm required a qualitative judgment involving an evaluation of the nature and gravity of the detention. [MIBP v WZAPN [2015] HCA 22]

The application of the reasonableness test in determining refugee status

The visa applicant applied for a protection visa on the basis that he feared persecution in Afghanistan because of his work as a truck driver transporting goods for foreign agencies. He claimed he would be imputed with a political opinion supportive of foreign agencies. The RRT accepted that if the visa applicant were intercepted by the Taliban on the roads on which he usually travelled, he would face a real chance of serious harm. However, it was not satisfied that he would face a real chance of persecution if he remained in Kabul, where he lived. The RRT was satisfied that the visa applicant could obtain employment as a jeweller in Kabul, as he had formerly done in Jaghori. The High Court held that the tribunal was required to address whether it was reasonable to expect the visa applicant to remain in Kabul and not to drive trucks outside it. The same considerations as were relevant to the ‘relocation principle’ applied when the tribunal identified an area where the visa applicant may be safe, so long as he or she remained there. [MIBP v SZSCA [2014] HCA 45]

Status of children born in Australia to unauthorised maritime arrivals

The applicant’s parents, Burmese nationals, arrived at Christmas Island without a visa. As a result of their arrival they became ‘unlawful non-citizens’ and ‘unauthorised maritime arrivals’ (UMA) for the purpose of the Migration Act. They were subsequently removed to Nauru, but later transferred to Australia as ‘transitory persons’ so that the applicant’s mother could give birth to the applicant. Following the applicant’s birth in Brisbane, the applicant’s father lodged a protection visa application on behalf of the applicant. The Minister’s delegate concluded the application was invalid as section 46A(1) of the Act prevented an UMA who was an unlawful non-citizen in Australia from making a valid application. The Full Federal Court confirmed that by operation of the Act, a child born to a UMA in Australia was also a UMA. [Plaintiff B9/2014 v MIBP [2014] FCAFC 178]

De facto relationships and the requirement to live together

The applicant applied for a Partner visa on the basis that he was in a de facto relationship with an Australian citizen. The definition of ‘de facto relationship’ in section 5CB(2)(c) of the Act required that the two people in the relationship must either live together, or ‘not live separately and apart on a permanent basis’. The tribunal accepted that the couple were in a de facto relationship. It noted that at the time of the application they had not cohabited and that they did not live together because they wanted to marry first and had not lived together after their marriage because the applicant had been in immigration detention. In finding that the requirements for a ‘de facto’ relationship had been met, the tribunal held that there was no requirement in the Act that the parties live together before a de facto relationship can be found to exist. The Federal Circuit Court held that the parties must have previously lived together before a de facto relationship can be found to exist. Setting aside that decision, the Full Federal Court held that there was no such requirement. [SZOXP v MIBP [2015] FCAFC 69]

Restrictions on the grant of multiple visas

The applicant, a former student visa holder, applied for a further student visa whilst still in Australia. The grant of that visa was subject to her meeting clause 3005 of Schedule 3 to the Regulations which required that a visa had not previously been granted to the applicant on the basis of the satisfaction of any of the criteria set out in that Schedule. The MRT found that the applicant had been granted her previous student visa on the basis of satisfying the criteria in Schedule 3 and therefore could not be granted the visa. At first instance, the Federal Circuit Court held that clause 3005 required the applicant not to have previously been granted a visa on the basis of satisfying the criteria for the grant of a visa in Schedule 2. As such, all subsequent applications for a visa were prohibited. Setting aside that decision, the Full Federal Court only prevented the grant of a subsequent visa in circumstances where the visa applicant had previously been granted a visa relying on the criteria in Schedule 3, not those where the applicant had satisfied the criteria on Schedule 2 without relying on Schedule 3. [Spakota v MIBP [2014] FCAFC 160]

A right to enter and reside in a country other than Australia

The applicant was a Nepalese national who sought a protection visa on the basis that he had a well-founded fear of persecution in Nepal. The RRT found that the applicant was not a person to whom Australia had protection obligations under section 36(3) of the Act as he had, under a 1950 Treaty between Nepal and India, a right to enter and reside in India as a matter of practical fact and reality. The Court held that the ‘right to enter and reside’ did not refer to a matter of practical fact and reality but rather included a ‘liberty, permission or privilege lawfully given’. Furthermore, such right was not confined to one sourced in domestic law but may be sourced in an executive act, such as a Treaty, executive policy or statement. [SZTOX v MIBP [2015] FCAFC 77]

Jurisdiction to review Subclass 457 decisions

The visa applicant applied for a Subclass 457 temporary business visa on the basis of his nomination by an Australian business, H. The nomination approval subsequently expired, and a delegate of the Minister refused the visa on that basis. On review, the MRT overturned that decision, finding that the nomination had not expired. The Federal Circuit Court quashed the MRT’s decision finding it did not have jurisdiction to conduct the review. It found the nomination had ceased. Furthermore section 338(2)(d) of the Act required that there be an approved nomination in respect of the visa applicant at the time the visa applicant sought review of a decision to refuse his Subclass 457. As the approval had ceased before the application for review was lodged with the MRT, the tribunal had no jurisdiction to determine the matter. [MIBP v Lee [2014] FCCA 2881]

Social justice and equity

The tribunals’ service charter expressed the commitment to providing a quality service to stakeholders. It set out general standards for client service covering day-to-day contact with the tribunals, responding to correspondence, arrangements for attending hearings, the use of interpreters, providing information that enabled effective engagement in the review process, and used language that was clear and easily understood. The service charter also outlined the process for providing feedback or making a complaint. Feedback assisted the tribunals to understand what was working well and where improvements could be made. The service charter was available in Arabic, Chinese, Dari, English, Farsi, Hindi, Korean, Punjabi, Tamil, Urdu and Vietnamese.

Table 7 sets out the tribunals’ performance during the year against service standards contained in the new service charter.

| Service standard | Report against standard for 2014–15 | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Be polite, respectful, courteous and prompt when we deal with you | All new members and staff attended induction training, which emphasised the importance of providing quality service to clients. | Achieved |

| 2. Use language that is clear and easily understood | Clear English was used in correspondence and forms. Staff used professional interpreters to communicate with clients from non-English speaking backgrounds. There was a language register listing staff available to speak to applicants in their language, where appropriate. The tribunals booked interpreters for hearings whenever they were requested by applicants and wherever possible accredited interpreters were used in hearings. Interpreters were used in 69% of hearings held (59% MRT and 90% RRT). The tribunals employed staff from diverse backgrounds who spoke more than 20 languages. | Achieved |

| 3. Acknowledge applications for review in writing within two working days | An acknowledgement letter was sent within two working days of lodgement in 84% of cases. | Achieved |

| 4. Include a contact name and telephone number on all our correspondence | All letters included a contact name and telephone number. | Achieved |

| 5. Help you to understand our procedures | The tribunals provided applicants with information about tribunal procedures at several stages during the review process. The website included a significant amount of information, including procedures and guidelines, forms and factsheets and frequently asked questions. General information about procedures was also available from case officers in the New South Wales and Victoria registries. An email enquiry address and an online enquiry form on the website were also available. | Achieved |

| 6. Provide information about where you can get advice and assistance | The website, service charter and application forms provided information about where applicants could get advice and assistance. ‘Factsheet MR2: Immigration Assistance’ notified applicants of organisations and individuals who could provide them with immigration assistance. The three application forms explained in 28 community languages how applicants could contact the Translating and Interpreting Service (TIS). | Achieved |

| 7. Provide information so that you can engage effectively in the review process | The tribunals provided applicants with information about tribunal procedures at several stages during the review process. The website included a significant amount of information, including procedures and guidelines, forms and factsheets and frequently asked questions. The Stakeholder Engagement Plan for 2012–14 set out how the tribunals would engage with stakeholders. Community liaison meetings were held twice during 2014–15 in Adelaide, Brisbane, Melbourne, Perth and Sydney. The tribunals had a feedback and complaints process outlined in the service charter and on the website. | Achieved |

| 8. Provide you with advance notice of the time and place of the hearing, if we invite you to a hearing | The Migration Regulations prescribed the periods for notifying applicants of MRT and RRT hearings. The tribunals invited applicants to hearings in accordance with the time frames referred to in the Migration Regulations. | Achieved |

| 9. Attempt to assist you if you have difficulty understanding or participating in the review process due to age or a physical, mental, psychological or intellectual condition, disability or frailty, or for social or cultural reasons | The tribunals employed a range of strategies to assist applicants who had difficulty understanding or participating in the review process. All offices were wheelchair accessible and hearing loops were available for use in hearing rooms. Whenever possible, requests for interpreters of a particular gender, dialect, ethnicity or religion were met. Hearings were able to be held by video conference. A national enquiry number 1300 361 969 was available from anywhere in Australia (calls were charged at the cost of a local call, more from mobile telephones). The tribunals had guidelines that addressed gender issues and the needs of vulnerable persons during the review process. | Achieved |

| 10. Provide reasons for our decisions | In most cases (except where a case was withdrawn or where the tribunals were notified of the applicant’s death), a written record of decision and the reasons for decision were provided to the applicant and to the department. In cases where the member made an oral decision, this was provided at the end of the hearing with an oral statement of reasons. Applicants were also able to request a written version of the oral statement of reasons. | Achieved |

| 11. Publish guidelines relating to the priority we give to particular cases | Guidelines for the priority to be given to particular cases were published in the annual constitution and prioritisation policy, which was available on the website. | Achieved |

| 12. Publish the time standards within which we aim to complete reviews | Time standards were available on the tribunals’ website. | Achieved |

| 13. Abide by the Australian Public Service (APS) Values and Code of Conduct (staff) available at www.apsc.gov.au | An induction program was available for new staff which included modules on the APS Values and the Code of Conduct. | Achieved |

|

14. Abide by the Member Code of Conduct (members) available on the website |

All new members attended induction training, which included the Member Code of Conduct. All members completed annual conflict of interest declaration forms and undertook performance reviews. | Achieved |

| 15. Publish information on caseload and tribunal performance | Information about caseload and performance in the current and previous financial years was published on the website under ‘statistics’. Further statistics, including those on the judicial review of tribunal decisions, were available in annual reports. | Achieved |

A high proportion of applicants had a language other than English as their first language. Clear language in letters and forms, and the availability of staff to assist applicants was important in ensuring that applicants understood their rights, and tribunal procedures and processes and could engage effectively in the review process.

The tribunal website was a significant information resource for applicants and others interested in the work of the tribunals. The publications and forms available on the website were regularly reviewed to ensure that information and advice was up-to-date and readily understood by clients.

The service charter was available on the website, along with the Strategic Plan, the Member Code of Conduct, the Interpreters’ Handbook and Principal Member Directions as to the conduct of reviews. The ‘representatives’ webpage supported representatives by bringing together the most commonly used resources and information. A ‘frequently asked questions’ page, arranged by topic, answered questions most commonly asked by applicants and representatives.

The tribunals had offices in Melbourne and Sydney which were open between 8.30 am and 5.00 pm on working days. The tribunals had an arrangement with the AAT for counter services and hearings at AAT offices in Adelaide, Brisbane and Perth. The tribunals also had a national enquiry number (1300 361 969) available from anywhere in Australia (calls were charged at the cost of a local call, more from mobile telephones). Persons who needed the assistance of an interpreter were able to contact the Translating and Interpreting Service on 131 450 for the cost of a local call.

The tribunals had a Reconciliation Action Plan, an Agency Multicultural Plan and a Workplace Diversity Program. Further information about these strategies and plans is set out in Part 4.

Complaints

In 2014–15, the tribunals received fewer than four complaints per 1,000 cases decided.

The tribunals’ service charter set out the standard of service that clients could expect from us. It also set out how clients could comment on, or complain about, the services that we provided.

Most issues or concerns that arose in the normal course of business were handled informally at the local level, and did not result in a formal complaint. Formal complaints had to be lodged in writing and were handled in accordance with the tribunals’ complaints policy.

In 2014–15, a person who was dissatisfied with how the tribunals dealt with a matter or with the standard of service that they received, and who was unable to resolve their concerns by contacting the officer dealing with their case, was able to forward a written complaint marked ‘confidential’ to the Complaints Officer.

Complaints about tribunal members were dealt with by the Principal Member. Complaints about staff or other matters were dealt with by the Registrar.

The tribunals’ complaints policy required that the receipt of a complaint was acknowledged within five working days and that a final response was provided, where possible, within 20 working days of receipt of the complaint.

When dealing with a complaint, the length of time before a final response could be provided depended on how much investigation was required. If more time was required, because of the complexity of the complaint or the need to consult with other persons before providing a response, the tribunals were required to advise the complainant of the progress that had been made in handling the complaint.

If a complaint was upheld, possible responses included an apology, a change to practice and procedure, or consideration of additional training and development for tribunal personnel.

A person could choose at any time to make a complaint to the Commonwealth Ombudsman. The Ombudsman, however, would not usually investigate a complaint that had not first been raised with the relevant agency.

Table 8 shows the number of formal complaints made to the tribunals over the last three years.

| 2014–15 | 2013–14 | 2012–13 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Complaints lodged | 69 | 56 | 33 |

| Cases decided | 21,567 | 24,729 | 19,347 |

| Complaints per 1,000 cases | <4 | <3 | <2 |

Of the complaints made in 2014–15, 41 related to member conduct, eight related to staff conduct, 14 related to member and staff conduct, and six related to tribunal policy and timeliness.

The tribunals provided substantive responses to all 69 complaints, responding to 57 out of 69 complaints within 20 working days.

Of the 69 complaints, the tribunals formed the view that eight of the complaints made during the year resulted in an opportunity for the tribunals to review organisational practices and procedures.

Table 9 sets out the complaints made to the Commonwealth Ombudsman over the last three years and the outcomes of the complaints resolved.

| 2014–15 | 2013–14 | 2012–13 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| New complaints | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Complaints resolved | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Administrative deficiency found | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Significant changes in the nature of functions or services

Amalgamation of the tribunals

The 2014–15 Budget included a measure to amalgamate the tribunals with the Administrative Appeals Tribunal (AAT) and the Social Security Appeals Tribunal (SSAT). The Tribunals Amalgamation Bill 2014 was introduced into the Senate on 3 December 2014, was passed by the Parliament on 13 May 2015, and received Royal Assent on 26 May 2015. The amalgamation took effect on 1 July 2015 and was part of the Government’s overall aim to provide a single body for external merits review and to generate efficiencies and savings through shared financial, human resources, information technology and governance arrangements.

On 1 July 2015 the tribunals became the Migration and Refugee Division (MRD) within the AAT. Most of the procedures that applied to the MRT and RRT will apply to the new Migration and Refugee Division and, with some exceptions, the Migration Act will remain as the legislation setting out the processes.

The Immigration Assessment Authority

The Migration and Maritime Powers (Resolving the Asylum Legacy Caseload) Act 2014 (the Legacy Act) received Royal Assent on 15 December 2014 and largely commenced on 18 April 2015. The legislation introduced a fast-track assessment process aimed at addressing an onshore caseload of certain unauthorised maritime arrivals (UMAs) known as ‘Fast-track applicants’. ‘Fast-track applicants’ are defined as being those UMAs who entered Australia on or after 13 August 2012 but before 1 January 2014 who have not been taken to a regional processing country and who have subsequently been permitted by the Minister to make a valid application for a protection visa. The Legacy Act established the Immigration Assessment Authority (IAA) as a distinct office within the RRT to review decisions to refuse a protection visa to fast-track applicants. The IAA will provide a limited form of review that is efficient, quick and free from bias. From 1 July 2015 the IAA became an independent authority within the MRD of the AAT.

In addition to the establishment of the IAA, the Legacy Act introduced temporary protection visas and safe haven enterprise visas, removed express links to the Convention relating to the Status of Refugees from the criteria for a protection visa, and removed the 90 day time period for processing protection visas.

Migration Amendment (Protection and Other Measures) Act 2015

The Migration Amendment (Protection and Other Measures) Act 2015 was passed by the parliament on 25 March 2015 and proclaimed on 18 April 2015. Among other things, this Act allowed for dismissal of applications to the MRT and RRT for non-appearance, for the Principal Member to issue guidance decisions, and allowed for oral reasons for decisions without the need for a written statement of reasons unless requested. The amendments were introduced to improve tribunal efficiency in decision making, particularly in relation to simpler and less meritorious cases.