Part 3 – Performance report

Contents

- Performance framework

- Financial performance

- Overview of caseload

- Conduct of reviews

- Interpreters at hearings

- Team profile – Hearing coordination units

- Outcomes of review

- Timeliness

- Judicial review

- Social justice and equity

- Complaints

- Migration agents

- Community and interagency liaison

- Major reviews

- Significant changes in the nature of functions or services

- Developments since the end of the year

- Case studies – Matters before the tribunals

The tribunals contributed to Australia's migration and refugee programs during the year through the provision of quality and timely reviews of decisions, completing 10,815 reviews. The outcomes of review were favourable to applicants in 34% of the cases decided.

Performance framework

The tribunals operate in a high-volume decision making environment where the case law and legislation are complex and technical. In this context, fair and lawful reviews are dependent on a number of factors, including resources, member numbers, skilled staff support services, and the success of strategies to respond to a substantial growth in caseloads.

Both tribunals have identical statutory objectives, set out in sections 353 and 420 of the Migration Act:

The tribunal shall, in carrying out its functions under this Act, pursue the objective of providing a mechanism of review that is fair, just, economical, informal and quick.

The key strategic priorities for the tribunals are to meet its statutory objectives through the delivery of consistent, high quality reviews, and timely and lawful decisions. Each review must be conducted in a way that ensures, as far as practicable, that the applicant understands the issues and has a fair opportunity to comment on or respond to any matters which might lead to an adverse outcome. The tribunals also aim to meet government and community expectations and to have effective working relationships with stakeholders. These priorities are reflected in the tribunals' plan.

During 2011–12, the tribunals' one outcome in the Portfolio Budget Statements was:

To provide correct and preferable decisions for visa applicants and sponsors through independent, fair, just, economical, informal and quick merits reviews of migration and refugee decisions.

The tribunals had one program contributing to this outcome, which was:

Final independent merits review of decisions concerning refugee status and the refusal or cancellation of migration and refugee visas.

Table 3.1 summarises the tribunals' performance against the program deliverables and key performance indicators that were set out in the 2011–12 Portfolio Budget Statements.

Table 3.1 – Performance information and results

Measure |

Result |

|---|---|

| Deliverables | |

8,300 cases |

The tribunals decided 10,815 cases. |

| Key performance indicators | |

Less than 5% of tribunal decisions set aside by judicial review |

0.2% of MRT and 0.8% of RRT decisions made in 2011–12 have been set aside by judicial review. |

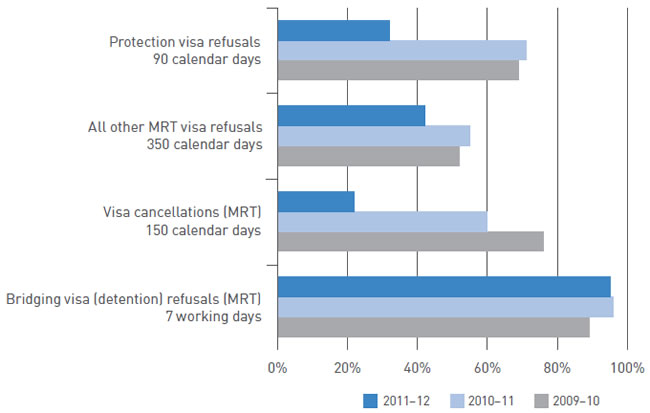

70% of cases decided within time standards |

95% of bridging visa (detention) refusals (MRT) were decided within seven working days. 32% of protection visa refusals were decided within 90 calendar days. 22% of visa cancellations (MRT) were decided within 150 calendar days. 42% of all other MRT visa refusals were decided within 350 days. |

Less than five complaints per 1,000 cases decided |

The tribunals received less than two complaints per 1,000 cases decided. |

40% of decisions published |

The tribunals published 42% of all decisions. |

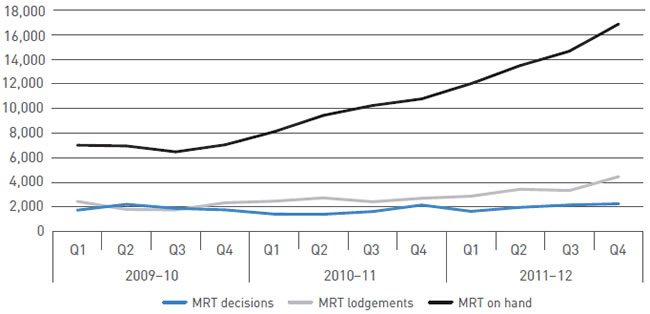

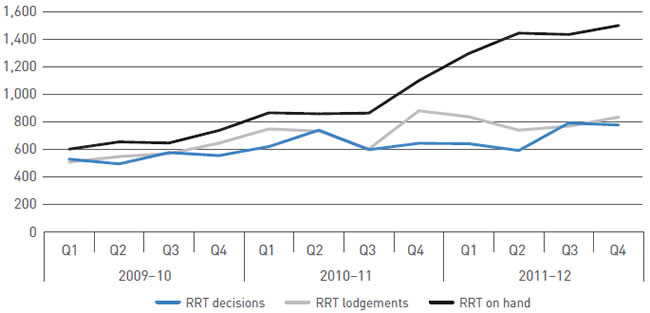

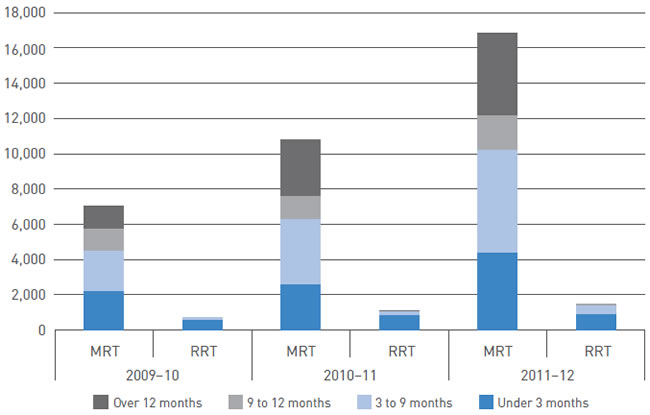

A feature of 2011–12 was an escalation in lodgements for both the MRT and the RRT, while some members were unavailable as they undertook work with the Independent Protection Assessment Office (IPAO).

As lodgements exceeded the tribunals' capacity to make decisions, the number of cases on-hand increased by 55% over the year. The tribunals have responded to this challenge with strategies to improve processing efficiency. The strategies in 2011–12 involved allocating groups or batches of like cases to members or groups of members and a stronger focus on member performance, with enhanced reporting on decision targets and the timeliness of case processing.

Financial performance

The MRT and the RRT are prescribed as a single agency, the 'Migration Review Tribunal and Refugee Review Tribunal' for the purposes of the FMA Act. The tribunals are funded based on a model which takes into account the number of cases decided and an assessment of fixed and variable costs. The tribunals' base funding in 2011–12 covers an amount to decide 8,300 cases and a marginal price for any case or cases above or below that number. The tribunals decided 10,815 cases and the tribunals' revenue as set out below takes into account an adjustment to appropriation based on the actual number of cases decided.

The tribunals' revenues from ordinary activities totaled $49.66 million and expenditure totaled $53.33 million, resulting in a net loss of $3.665 million and depreciation worth $1.48 million. The tribunals received approval from the Minister for Finance and Deregulation for an operating loss of $800,000 for 2011–12. Contributing factors to the loss being greater than expected were adjustments to leave provisions and additional superannuation charges.

The 2011–12 Budget provided increased appropriations of $13.9 million over the four years of the forward estimates. The increased appropriations to the tribunals were offset by increases in the MRT and RRT application fees and a new fee structure from 1 July 2011.

The tribunals administer application fees on behalf of the government. Details of administered revenue are set out in the financial statements. The financial statements for 2011–12, which are set out in part 5, have been audited by the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) and received an unqualified audit opinion.

Overview of caseload

The tribunals received 17,293 lodgements during the year, decided 10,815 cases and had 18,364 cases on-hand at the end of the year.

Statistical tables and charts covering the MRT and RRT caseloads are set out in the following pages.

Lodgements

Lodgements of applications for review tend to fluctuate between years, according to trends in primary applications and in primary decision making, and changes to visa criteria and jurisdiction.

The MRT has jurisdiction to review a wide range of visa, sponsorship and other decisions relating to migration and temporary entry visas. Only a small proportion of primary decisions made by the department come to the MRT.

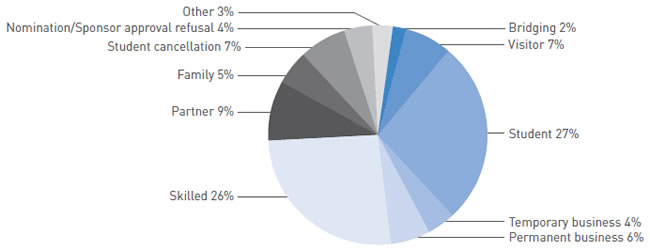

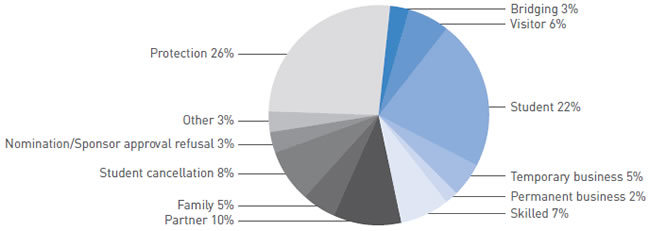

In 2011–12, the MRT had very large increases in skill linked refusal, permanent business refusal and student visa refusal lodgements. The proportion of applications in relation to persons living in Australia, particularly overseas students, has increased progressively over the past three years.

The MRT's jurisdiction in relation to visas applied for outside Australia depends on whether there is a requirement for an Australian sponsor or for a close relative to be identified in the application. These cases are mainly in the skilled, visitor, partner and family categories. In 2011–12, approximately 20% of visa refusal applications to the MRT related to persons outside Australia seeking a visa.

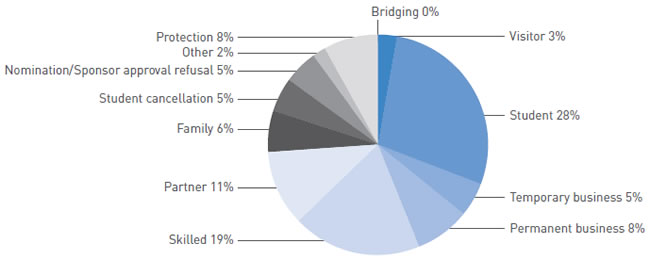

The RRT has jurisdiction to review decisions to refuse protection visas. Following an announcement by the Minister that a single protection visa system would commence from 24 March 2012, this includes protection visa refusals for irregular maritime arrivals. Also on 24 March 2012 the criteria for protection visas were amended to provide alternative 'complementary protection' grounds. These amendments applied to all undecided RRT applications, as well as new applications.

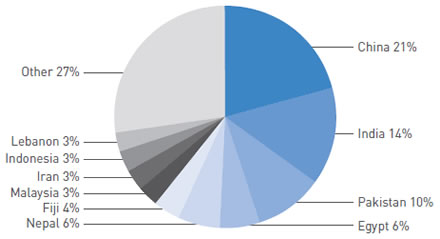

All protection visa applicants within Australia have a right to apply for review if their protection visa application is refused. In 2011–12, over 4,400 protection visa applications were refused at the primary level and about 91% of refused applicants applied to the RRT for review. While lodgements to the RRT were made by applicants from over 96 countries, 56% of the RRT's lodgements involved nationals of five countries – the People's Republic of China (China), India, Pakistan, Egypt and Nepal. The largest number of applications was from nationals of China, with 58% more applications received from nationals of China than from the next largest source country, India.

The RRT received its first application from an irregular maritime arrival on 8 May 2012. Between then and the end of the financial year, 55 applications were lodged from applicants from Afghanistan (28), Iran (19), Pakistan (five) and Iraq (three).

Applicants to both tribunals tend to be located in the larger metropolitan areas. Thirty-six per cent of all applicants resided in New South Wales, mostly in the Sydney region. Approximately 35% of applicants resided in Victoria, 12% in Queensland, 9% in Western Australia, 5% in South Australia, 1% each in the Australian Capital Territory and in the Northern Territory, and less than 1% in Tasmania. Over the past five years, the proportion of lodgements from New South Wales has decreased significantly – from 59% in 2006–07 to 36% in 2011–12. In 2011–12 the proportion of lodgements from Victoria increased to 35%, after remaining relatively stable at 25% since 2006–07.

Cases involving applicants held in immigration detention comprised 3% of the cases before the tribunals, with most applicants within Australia holding a bridging or substantive visa during the course of the review. Initially most irregular maritime arrival applicants were in detention but increasingly more are being released into the community on bridging visas before or shortly after lodging their RRT application.

Statistics

Caseload overview

2011–12 |

2010–11 |

2009–10 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| MRT | |||

On-hand at start of year |

10,786 |

7,048 |

6,295 |

Lodged |

14,088 |

10,315 |

8,333 |

Decided |

8,011 |

6,577 |

7,580 |

On-hand at end of year |

16,863 |

10,786 |

7,048 |

| RRT | |||

On-hand at start of year |

1,100 |

738 |

624 |

Lodged |

3,205 |

2,966 |

2,271 |

Decided |

2,804 |

2,604 |

2,157 |

On-hand at end of year |

1,501 |

1,100 |

738 |

| TOTAL MRT AND RRT | |||

On-hand at start of year |

11,886 |

7,786 |

6,919 |

Lodged |

17,293 |

13,281 |

10,604 |

Decided |

10,815 |

9,181 |

9,737 |

On-hand at end of year |

18,364 |

11,886 |

7,786 |

Lodgements

2011–12 |

2010–11 |

2009–10 |

% change 2010–11 to 2011–12 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MRT | ||||

Visa refusal – Bridging |

267 |

264 |

139 |

+1% |

Visa refusal – Visitor |

944 |

920 |

690 |

+3% |

Visa refusal – Student |

3,820 |

3,138 |

1,937 |

+22% |

Visa refusal – Temporary business |

634 |

621 |

567 |

+2% |

| Visa refusal – Permanent business | 806 |

661 |

285 |

+22% |

Visa refusal – Skilled |

3,606 |

635 |

1,182 |

+468% |

Visa refusal – Partner |

1,345 |

1,348 |

1,157 |

0% |

Visa refusal – Family |

727 |

672 |

739 |

+8% |

Cancellation – Student |

1,043 |

1,107 |

875 |

-6% |

Nomination/Sponsor approval refusal |

516 |

513 |

370 |

+1% |

Other |

380* |

436* |

392* |

-13% |

Total MRT |

14,088 |

10,315 |

8,333 |

+37% |

| RRT | ||||

China |

689 |

819 |

751 |

-16% |

India |

435 |

221 |

138 |

+97% |

Pakistan |

312 |

102 |

53 |

+206% |

Egypt |

185 |

181 |

52 |

+2% |

Nepal |

184 |

107 |

28 |

+72% |

Fiji |

130 |

252 |

243 |

-48% |

Malaysia |

112 |

172 |

201 |

-35% |

Iran |

107 |

58 |

27 |

+84% |

Indonesia |

98 |

146 |

115 |

-33% |

Lebanon |

94 |

125 |

84 |

-25% |

Other |

859 |

783 |

579 |

+10% |

Total RRT |

3,205 |

2,966 |

2,271 |

+8% |

Total MRT and RRT |

17,293 |

13,281 |

10,604 |

+30% |

* In 2011–12, the MRT 'Sponsor approval refusal' and 'other' case categories changed. Nomination approval refusals were removed from the 'other' case category and added in to the 'sponsor approval refusal' category. These changes have been applied to the statistical data for previous years. As a result, data for 2010–11 and 2009–10 in the above tables for these case categories will vary from data set out in previous annual reports.

MRT lodgements, decisions and cases on-hand by quarter

MRT lodgements by case type

MRT and RRT cases on-hand

RRT lodgements, decisions and cases on-hand by quarter

RRT lodgements by country of reference

MRT and RRT decisions

Cases on-hand

2011–12 |

2010–11 |

2009–10 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| MRT | |||

Visa refusal – Bridging |

12 |

9 |

12 |

Visa refusal – Visitor |

607 |

357 |

189 |

Visa refusal – Student |

5,203 |

3,716 |

1,898 |

Visa refusal – Temporary business |

989 |

911 |

645 |

Visa refusal – Permanent business |

1,415 |

841 |

328 |

Visa refusal – Skilled |

3,555 |

711 |

1,034 |

Visa refusal – Partner |

1,968 |

1,731 |

1,320 |

Visa refusal – Family |

1,003 |

833 |

632 |

Cancellation – Student |

811 |

600 |

289 |

Nomination/Sponsor approval refusal |

917 |

741 |

439 |

Other |

383 |

336 |

262 |

Total MRT |

16,863 |

10,786 |

7,048 |

| RRT | |||

China |

303 |

279 |

219 |

India |

174 |

80 |

39 |

Pakistan |

210 |

59 |

16 |

Egypt |

81 |

112 |

18 |

Nepal |

89 |

56 |

13 |

Fiji |

61 |

64 |

130 |

Malaysia |

36 |

17 |

32 |

Iran |

55 |

19 |

12 |

Indonesia |

17 |

36 |

10 |

Lebanon |

46 |

49 |

19 |

Other |

429 |

329 |

230 |

Total RRT |

1,501 |

1,100 |

738 |

Total MRT and RRT |

18,364 |

11,886 |

7,786 |

Timeliness of reviews

2011–12 |

2010–11 |

2009–10 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| AVERAGE TIME TAKEN (DAYS)* | |||

Bridging visa (detention) refusals (MRT) |

7 |

7 |

7 |

Visa cancellations (MRT) |

224 |

150 |

123 |

All other MRT visa refusals |

461 |

337 |

311 |

Protection visa refusals |

149 |

99 |

99 |

| PERCENTAGE DECIDED WITHIN TIME STANDARDS* | |||

| Bridging visa (detention) refusals (MRT) – seven working days | 95% |

96% |

89% |

Visa cancellations (MRT) – 150 calendar days |

22% |

60% |

76% |

All other MRT visa refusals – 350 calendar days |

42% |

55% |

52% |

Protection visa refusals – 90 calendar days |

32% |

71% |

69% |

* Calendar days, other than for bridging (detention) cases which is by working days. Time standards are as set out in the Migration Act and Migration Regulations or in the 2011–12 Portfolio Budget Statements. For MRT cases, time taken is calculated from date of lodgement. For RRT cases, time taken is calculated from the date the department's documents are provided to the RRT. The average time from lodgement of an application for review to receipt of the department's documents was 20 days for MRT cases and seven days for RRT cases.

Number and age of cases on-hand

Percentage of cases decided within time standards

Outcomes of review

2011–12 |

2010–11 |

2009–10 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| MRT | |||

Primary decision set aside or remitted |

2,912 |

2,728 |

3,429 |

Primary decision affirmed |

3,133 |

2,356 |

2,700 |

Application withdrawn by applicant |

1,180 |

754 |

796 |

No jurisdiction to review* |

786 |

739 |

655 |

Total |

8,011 |

6,577 |

7,580 |

| RRT | |||

Primary decision set aside or remitted |

750 |

626 |

514 |

Primary decision affirmed |

1,899 |

1,815 |

1,540 |

Application withdrawn by applicant |

86 |

53 |

21 |

No jurisdiction to review* |

69 |

110 |

82 |

Total |

2,804 |

2,604 |

2,157 |

* No jurisdiction decisions include applications not made within the prescribed time limit, not made in respect of reviewable decisions or not made by a person with standing to apply for review. The tribunals' procedures provide for an applicant to be given an opportunity to comment on any jurisdiction issue before a decision is made. Some cases raise complex questions as to whether a matter is reviewable and whether a person has been properly notified of a decision and of review rights.

Cases decided and set aside rates

2011–12 |

2010–11 |

2009–10 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Cases |

% set aside |

Cases |

% set aside |

Cases |

% set aside |

|

| MRT | ||||||

Visa refusal – Bridging |

264 |

12% |

267 |

12% |

151 |

15% |

Visa refusal – Visitor |

695 |

65% |

752 |

59% |

679 |

58% |

Visa refusal – Student |

2,334 |

31% |

1,320 |

36% |

738 |

42% |

Visa refusal – Temporary business |

556 |

26% |

355 |

25% |

571 |

30% |

Visa refusal – Permanent business |

233 |

29% |

148 |

32% |

278 |

46% |

Visa refusal – Skilled |

762 |

36% |

958 |

53% |

1,895 |

42% |

Visa refusal – Partner |

1,108 |

55% |

937 |

62% |

1,268 |

66% |

Visa refusal - Family |

557 |

44% |

471 |

39% |

546 |

42% |

Cancellation – Student |

833 |

21% |

796 |

25% |

811 |

41% |

Nomination/Sponsor approval refusal |

340 |

15% |

214 |

24% |

267 |

27% |

Other |

329 |

43% |

359 |

33% |

375 |

38% |

Total MRT |

8,011 |

36% |

6,577 |

41% |

7,580 |

45% |

| RRT | ||||||

China |

665 |

17% |

759 |

22% |

761 |

27% |

India |

343 |

6% |

181 |

7% |

169 |

6% |

Pakistan |

161 |

50% |

59 |

36% |

52 |

42% |

Egypt |

216 |

61% |

87 |

36% |

44 |

52% |

Nepal |

151 |

9% |

64 |

16% |

21 |

33% |

Fiji |

133 |

20% |

318 |

13% |

127 |

15% |

Malaysia |

93 |

3% |

187 |

2% |

196 |

3% |

Iran |

71 |

80% |

51 |

76% |

20 |

80% |

Indonesia |

116 |

3% |

120 |

4% |

122 |

7% |

Lebanon |

99 |

41% |

95 |

31% |

80 |

26% |

Other |

756 |

34% |

683 |

39% |

565 |

31% |

Total RRT |

2,804 |

27% |

2,604 |

24% |

2,157 |

24% |

Total MRT and RRT |

10,815 |

34% |

9,181 |

37% |

9,737 |

40% |

Conduct of reviews

The procedures of the MRT and the RRT are inquisitorial rather than adversarial in nature. Proceedings before the tribunals do not take the form of litigation between parties. The review is an inquiry in which the member identifies the issues or criteria in dispute, initiates investigations or inquiries to supplement evidence provided by the applicant and the department and ensures procedural momentum. At the same time, the member must maintain an open and impartial mind.

Applicants appointed a representative to assist or represent them in 65% of MRT cases decided and in 61% of RRT cases decided.

In 2011–12 6,663 hearings were arranged for MRT cases and 4,267 were completed or adjourned. Out of the 4,182 hearings arranged for RRT cases, 2,651 were completed or adjourned.

Cases which do not proceed to hearing include cases where a decision favourable to the applicant is made prior to the hearing date, cases where the applicant does not attend the hearing or which can be decided without a hearing being required, and cases where the applicant withdraws their application before the hearing. Favourable decisions on the papers were made in 5% of MRT cases (including in 16% of skilled visa refusal cases) and in 1% of RRT cases.

Most hearings are held in person. Video links were used in 13% of hearings. The average duration of MRT hearings was 75 minutes and the average duration of RRT hearings was 141 minutes. Two or more hearings were held in 13% of RRT cases and in 3% of MRT cases.

Interpreters at hearings

The tribunals aim to identify, implement and promote best practice in interpreting at hearings. High quality interpreting services are fundamental to the work of the tribunals. In 2011–12, the tribunals arranged 10,845 hearings nation-wide. Interpreters were required for 58% of MRT hearings and for 83% of RRT hearings, across approximately 84 languages and dialects.

The tribunals have a national Interpreter Advisory Group (IAG), which has the overall objective of ensuring, as far as possible, that the tribunals maintain access to a high standard of interpreters and that tribunal policies and practices facilitate this. The IAG has a national membership comprising both members and tribunal officers.

All Graduates was the tribunals' contracted interpreting services provider during 2011–12. After an open tender process, ONCALL Interpreters and Translators was selected to provide interpreting services from 1 July 2012.

TEAM PROFILE

Hearing coordination units

The tribunals conduct hearings to ensure that applicants are given a reasonable opportunity to present their case before a member. The main function of the hearing coordination units in the Victoria and New South Wales registries is to support members in the conduct of hearings.

The duties of tribunal hearing attendants include greeting and explaining the hearing process to parties prior to the commencement of the hearing; conducting hearing preliminaries such as the swearing-in of parties; operating recording equipment; and making national and international phone calls and videoconference calls to enable remote applicants and witnesses to present evidence while the hearing is in session.

Hearing coordinators and hearing schedulers are responsible for arranging suitably qualified interpreters to attend hearings, booking videoconference facilities, and ensuring that everything runs smoothly on the day of the hearing itself.

Hearings are conducted on the tribunals' premises in Sydney and Melbourne, and in the offices of the AAT in Adelaide, Brisbane and Perth. In 2011–12, the Victoria and New South Wales registries arranged 10,845 hearings in Sydney and Melbourne, with 6,881 hearings completed. Thirty per cent of cancelled hearings were cancelled because the review applicant failed to appear on the day. In 2011–12, 13% of hearings were conducted by videoconference or telephone because of the location of one or more of the hearing parties.

Since May 2012, arranging and conducting hearings for irregular maritime arrival applicants has proven a challenge for hearings staff. The number of hearings by videoconference will continue to increase as a greater number of cases will involve applicants living in remote detention facilities, or elsewhere in regional and rural Australia.

Melbourne hearing coordinators. From left to right, Mr John Hough, Ms Terrie Hancock, Ms Elizabeth Patrick, Mr Jon Richards, Mr Preston Hall and Mr Rex Hardjadibrata.

Outcomes of review

A written statement of decision and reasons is prepared in each case and provided to both the applicant and the department.

The MRT set aside or remitted the primary decision in 36% of cases decided and affirmed the primary decision in 39% of cases decided. The remaining 25% of cases were either withdrawn by the applicant or were cases where the tribunal decided it had no jurisdiction to conduct the review.

The RRT set aside or remitted the primary decision in 27% of cases decided and affirmed the primary decision in 68% of cases decided. The remaining 5% of cases were either withdrawn by the applicant or were cases where the tribunal decided it had no jurisdiction to conduct the review.

Two irregular maritime arrival cases were decided in 2011–12; the primary decision was set aside in both cases.

Three RRT cases were remitted to the department on complementary protection grounds in 2011–12.

The fact that a decision is set aside by the tribunal is not necessarily a reflection on the quality of the primary decision, which may have been correct and reasonable based on the information available at the time of the decision. Departmental officers in general make sound decisions across a very large volume of cases and make favourable decisions in the majority of cases.

Applications for review typically address the issues identified by the primary decision maker by providing submissions and further evidence to the tribunal. By the time of the tribunal's decision, there is often considerable additional information before the tribunal, and there may be court judgments or legislative changes which affect the outcome of the review.

Applicants were represented in 64% of cases decided. Most commonly, representation was by a registered migration agent. In cases where applicants were represented, the set aside rate was higher than for unrepresented applicants. The difference was most notable for RRT cases where the set aside rate was 37% for represented applicants and 11% for unrepresented applicants. It is worth noting that unrepresented applicants may or may not have sought advice on their prospects of success before applying for review, and only 65% of unrepresented applicants to the RRT attend hearings, compared to almost 83% of applicants who have a representative. For the MRT, there was also an appreciable difference in outcome for unrepresented applicants. The set aside rate was 39% for represented applicants and 31% for unrepresented applicants.

A total of 158 cases (1% of the cases decided) were referred to the department for consideration under the Minister's intervention guidelines. These cases raised humanitarian or compassionate circumstances which members considered should be drawn to the attention of the Minister.

Timeliness

The tribunals aim to resolve cases quickly. Members actively manage their caseloads from the time of allocation until decision. Members are expected to identify quickly the relevant issues in a review and the necessary course of action to enable the review to be conducted as effectively and efficiently as possible. Older cases are monitored by senior members to assist in minimising unnecessary delays.

Some cases cannot be decided within the relevant time standard. These include cases where hearings need to be rescheduled because of illness, the unavailability of an interpreter, cases where the applicant requests further time to comment or respond to information, cases where new information becomes available, and cases where an assessment or information needs to be obtained from another body or agency. For irregular maritime arrival cases, there may be additional difficulties associated with scheduling hearings at remote detention centres or for applicants without a stable residential address.

Increasingly, cases cannot be decided within the relevant time standards due to the limited capacity to deal with growing lodgements. While the tribunals have improved capacity and processing efficiencies, lodgements have overwhelmed these efforts. The government's decision to appoint additional members, the return of members from IPAO work and the implementation of recommendations contained in the Lavarch Review are expected to have an impact in the second half of 2012–13.

As required by section 440A of the Migration Act, the Principal Member reports every four months on the RRT's compliance with the 90 day period for RRT reviews. These reports are provided to the Minister for tabling in parliament. In 2011–12, only 32% of RRT cases were decided within 90 days; the average time to decision was 149 days, and this was a significant deterioration from 71% in 2010–11.

Judicial review

For persons wishing to challenge an MRT or RRT decision, two avenues of judicial review are available. One is to the Federal Magistrates Court for review under section 476 of the Migration Act. The other is to the High Court pursuant to paragraph 75(v) of the Constitution. Decision-making under the Migration Act remains an area where the level of court scrutiny is very intense and where a tribunal decision may be upheld or overturned at successive levels of appeal.

The applicant and the Minister are generally the parties to a judicial review of a tribunal decision. Although joined as a party to proceedings, the tribunals do not take an active role in litigation. As a matter of course, the tribunals enter a submitting appearance, consistent with the principle that an administrative tribunal should not generally be an active party in judicial proceedings challenging its decisions.

In 2011–12 the number of RRT decisions taken to judicial review increased in comparison with previous years. The number of MRT decisions taken to judicial review was consistent with previous years. Table 3.2 sets out judicial review applications and outcomes as at 10 August 2012, in relation to the tribunal decisions made over the last three years.

Table 3.2 – Judicial review applications and outcomes

MRT |

RRT |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

2011–12 |

2010–11 |

2009–10 |

2011–12 |

2010–11 |

2009–10 |

|

Tribunal decisions |

8,011 |

6,577 |

7,580 |

2,804 |

2,604 |

2,157 |

Court applications |

254 |

255 |

248 |

660 |

536 |

527 |

% of tribunals decisions |

3.2% |

3.9% |

3.3% |

23.5% |

20.6% |

24.4% |

Applications resolved |

109 |

239 |

245 |

233 |

507 |

520 |

Decision upheld or otherwise resolved |

96 |

206 |

166 |

210 |

468 |

476 |

Set aside by consent or judgement |

13 |

33 |

79 |

23 |

39 |

44 |

Set aside decisions as % of judicial applications resolved |

11.9% |

13.8% |

32.2% |

9.9% |

7.7% |

8.5% |

Set aside decisions as % of decisions made |

0.2% |

0.5% |

1.0% |

0.8% |

1.5% |

2.0% |

Note: The table above shows the number of tribunal decisions made during each financial year that have been the subject of a judicial review application and the judicial review outcome for those cases. The outcome of judicial review applications is reported on completion of all court appeals against a tribunal decision. Previous years' figures are affected if a further court appeal is made in relation to a case previously counted as completed.

Of the decisions made by the tribunals in 2011–12, only a small percentage (0.2% of MRT decisions and 0.8% of RRT decisions) have been set aside or quashed by the courts. If a tribunal decision is set aside or quashed, the court order is usually for the matter to be remitted to the tribunal to be reconsidered. In such cases, the tribunal (constituted by a different member) must reconsider the case and make a fresh decision, taking into account the decision of the court and any further evidence or changed circumstances. In 78% of MRT cases and 33% of RRT cases reconsidered in 2011–12 the tribunal made a new decision favourable to the applicant.

Summaries of some notable judicial decisions since 1 July 2011 are set out on the following pages. These decisions had an impact on the tribunals' decision making or procedures, or on the operation of judicial review in relation to tribunal decisions.

As there are restrictions on identifying applicants for protection visas, letter codes or reference numbers are used by the courts in these cases. Unless stated otherwise, references are to the Migration Act and Migration Regulations. The Minister is a party in most cases, and “MIAC” is used to identify the Minister in the abbreviated citations provided.

MRT – failure to adjourn a review

Ms Li was refused a skilled – independent overseas student visa by the department because she did not have a positive assessment of her skills in her nominated occupation. Shortly after the MRT hearing, Ms Li received the results of an unsuccessful skills assessment and sought review of that assessment from the assessing authority. She asked that the MRT forbear from making any decision until the assessing authority's review had been finalised. The MRT proceeded to make its decision, finding Ms Li had been provided with enough opportunities to have her skills assessed. On appeal, the Full Federal Court held that the MRT's refusal to adjourn or to properly consider the request for an adjournment denied Ms Li a reasonable opportunity to give evidence and present her case as required by section 360(1) of the Migration Act. The majority of the court held that a failure to properly consider a request for an adjournment or an unreasonable refusal to adjourn may mean that the tribunal has not discharged its core statutory function of reviewing the decision and will amount to a breach of a statutory requirement to act fairly. [MIAC v Li [2012] FCAFC 74]

MRT – application form

The visa applicant, who was not in immigration detention, lodged application Form M2 (for applicants in detention) with the MRT. Section B, signed by Ms P, appointed her as the applicant's representative and Section C indicated correspondence should be sent to her as the 'authorised recipient'. On the same day, the correct Form M1 (applicants not in detention) was lodged which also identified Ms P as the representative. The completed Section B from Form M2 was attached to Form M1 although Form M1 Section F indicated that correspondence should be sent 'to another person'. No other person was named. The MRT sent Ms P a hearing invitation. The Full Federal Court held that Form M2 was not an approved form in the case of the appellant and by lodging it he did not comply with section 347(1)(a). Sections 347 and 348 require that an application for review of an MRT-reviewable decision will only be made validly by use of 'the approved form'. The majority of the court held that the MRT committed jurisdictional error by failing to give notice to the applicant of its invitation to a hearing when it only sent the invitation to Ms P, as a person can only be appointed as authorised recipient under section 379G(1) in respect of an application for review that was properly made. [SZJDS v MIAC [2012] FCAFC 27]

MRT – approval of assessing authority

Mr Singh applied for a skilled graduate visa and in September 2009 obtained a successful skills assessment for his nominated occupation of cook from Trades Recognition Australia (TRA). The MRT found that information provided in his visa application and to TRA about his employment was incorrect and on this basis there was evidence that Mr Singh had given, or caused to be given, information that was false or misleading in a material particular and that Mr Singh did not satisfy Public Interest Criterion 4020 for the purposes of clause 485.224(a) of Schedule 2 to the Migration Regulations.

Before the court, the Minister conceded that TRA had not been validly specified as the relevant assessing authority for the occupation of cook at the time of the MRT decision. The court held that the visa criteria applicable at the time of the MRT's decision did not include criterion 485.214 or criterion 485.221 because no relevant assessing authority had been lawfully approved or specified for the purposes of those criteria. As a result, the court found the MRT was in error in finding the information provided by Mr Singh was false or misleading in a material particular. [Singh v MIAC [2012] FMCA 145]

MRT – 'time of application' criteria

Mr Patel applied for a skilled graduate visa and gave 'Family Counsellor' as his nominated occupation in his application. A requirement is that this be closely related to his Australian educational qualification, which was a Master of Information Systems. He later provided a skills assessment as an Environmental Health Officer and later claimed that he had intended to nominate the occupation of Computing Professional. On appeal, the Federal Court distinguished the judgement of the High Court in Berenguel v MIAC [2010] HCA 8, finding that clause 485.214 of Schedule 2 to the Migration Regulations requires an application for a skills assessment to be made at the time of application, and that as such the occupation or assessment could not be modified after the date of application. [Patel v MIAC [2011] FCA 1220]

Mr Singh lodged an application for a skilled visa on 17 June 2008, stating on the application that he had not applied for an Australian Federal Police (AFP) check. He then applied for an AFP check on 9 July 2008. The MRT found that Mr Singh did not meet the requirements in clause 485.216 of Schedule 2 to the Migration Regulations, which required that the visa application be accompanied by evidence that the applicant has applied for an AFP check during the 12 months immediately before the day when the application is made. The court held that clause 485.216 requires that the evidence of an application for an AFP check must accompany the application, and that in Mr Singh's case it did not. By implication, the judgement distinguishes Berenguel v MIAC [2010] HCA 8. [Singh v MIAC [2011] FMCA 982]

MRT – cancellation of student visa

Ms Kim's student visa was cancelled for non-compliance with visa condition 8202, which requires that the holder of the visa has not been certified for not making satisfactory course progress. The court held that the MRT was not required to consider the validity of the certification issued by the education provider for the purposes of condition 8202 and that it is the fact of certification, or the existence of a certification that was the non-compliance for the purposes of condition 8202 and not the underlying facts that led the provider to issue the certification. Further, the court held that the decision by an education provider to issue a certificate is not reviewable by the MRT. [Kim v MIAC [2011] FMCA 780]

MRT – validity of independent expert opinions in domestic violence matters

Mr Maman claimed he was subjected to domestic violence by his spouse. A delegate of the Minister refused the visa based on the opinion of an independent expert that Mr Maman had not suffered domestic violence. On review, the MRT requested an opinion from a second independent expert. The second expert also concluded that Mr Maman was not a victim of domestic violence, and referred to claims made in a letter to the department from Mr Maman's spouse. The Full Federal Court held that the rules of procedural fairness required at least the gist of the letter to be disclosed to Mr Maman by the independent experts before either expert formed an opinion and that the failure to do so had the consequence that there never was an 'opinion' which was to be taken as 'correct' by either the delegate or the MRT. Relying on the procedurally flawed 'opinion' led to jurisdictional error in the MRT's decision. [MIAC v Maman [2012] FCAFC 13]

RRT – putting adverse information to an applicant at a hearing

The visa applicant applied for a protection visa on the basis that he feared persecution in Afghanistan. During the hearing the RRT explained that it wished to discuss information that would be a reason for affirming the decision, as required by section 424AA. It explained that the applicant would be asked to respond and be entitled to seek additional time to comment or respond to that information. The RRT then put to the applicant various inconsistencies which it noted may be relevant to establishing his lack of credibility and invited comment. On appeal, the Federal Court concluded that section 424AA(b)(iii) does not require the RRT to advise an applicant of the right to seek additional time separately and for each piece of information, in circumstances where the RRT makes clear in a general statement that the invitation to seek additional time extends to all information put forward for comment. The judgement also confirmed that the RRT need not adjourn an oral hearing where it decides to adjourn a review to provide additional time for comment on section 424A information. [SZPZJ v MIAC [2012] FCA 18]

Social justice and equity

The tribunals' service charter expresses our commitment to providing a professional and courteous service to review applicants and other persons with whom we deal. It sets out general standards for client service covering day-to-day contact with the tribunals, responding to correspondence, arrangements for attending hearings, the use of interpreters and the use of clear language in decisions. The service charter is available in 10 community languages (Arabic, Bengali, Chinese, Hindi, Korean, Nepali, Punjabi, Tamil, Turkish and Vietnamese).

The tribunals have engaged Buchan Consulting to conduct external surveys of review applicants, interpreters and migration agents. The surveys will allow the tribunals to gauge perceptions of its performance across a range of criteria and will assist in future strategic planning. This is expected to be completed by September 2012.

Table 3.3 sets out the tribunals' performance during the year against service standards contained in the service charter.

Table 3.3 – Report against service standards

Service standard |

Report against standard for 2011–12 |

Outcome |

|---|---|---|

1. Be helpful, prompt and respectful when we deal with you |

All new members and staff attended induction training emphasising the importance of providing quality service to clients. |

Achieved |

2. Use language that is clear and easily understood |

Clear English is used in correspondence and forms. Staff use professional interpreters to communicate with clients from non-English speaking backgrounds. There is a language register listing staff available to speak to applicants in their language, where appropriate. |

Achieved |

3. Listen carefully to what you say to us |

The tribunals book interpreters for hearings whenever they are requested by applicants and wherever possible accredited interpreters are used in hearings. Interpreters were used in 68% of hearings held (58% MRT and 83% RRT). The tribunals employ staff from diverse backgrounds who speak more than 20 languages. Staff use professional interpreters to communicate with clients from non-English speaking backgrounds in hearings. A review of the tribunals' Stakeholder Engagement Plan was undertaken and a revised version for 2012–14 published in June 2012. It sets out how the tribunals will engage with stakeholders and the engagement activities planned for 2012–14 and beyond. Community liaison meetings were held twice during 2011–12 in Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, Perth and Adelaide. The tribunals have a formal complaints, compliments and suggestions process. |

Achieved |

4. Acknowledge applications for review in writing within two working days |

An acknowledgement letter was sent within two working days of lodgement in more than 87% of cases. |

87% |

5. Include a contact name and telephone number on all our correspondence |

All letters include a contact name and telephone number. |

Achieved |

6. Help you to understand our procedures |

The tribunals provide applicants with information about tribunal procedures at several stages during the review process. The tribunals' website includes a significant amount of information, including forms and factsheets. Case officers are available in the New South Wales and Victoria registries to explain procedures over the counter or the telephone. The tribunals have an email enquiry address applicants can use to seek general information about procedures. |

Achieved |

7. Provide information about where you can get advice and assistance |

The tribunals' website, service charter and application forms provide information about where applicants can get advice and assistance. Factsheet MR2: Immigration Assistance notifies applicants of organisations and individuals who can provide them with immigration assistance. The tribunals' application forms R1, M1 and M2 explain in 28 community languages how applicants may contact the Translating and Interpreting Service (TIS). |

Achieved |

8. Attempt to assist you if you have special needs |

The tribunals employ a range of strategies to assist applicants with special needs. Our offices are wheelchair accessible and hearing loops are available for use in hearing rooms. Whenever possible, requests for interpreters of a particular gender, dialect, ethnicity or religion are met. Hearings can be held by video. A national enquiry number is available from anywhere in Australia (calls are charged at the cost of a local call, more from mobile telephones). |

Achieved |

9. Provide written reasons when we make a decision |

In all cases, a written record of decision and the reasons for decision is provided to the review applicant and to the department. |

Achieved |

10. Publish guidelines relating to the priority we give to particular cases |

Guidelines relating to the priority to be given to particular cases are published in the annual caseload and constitution policy, which is available on the tribunals' website. |

Achieved |

11. Publish the time standards within which we aim to complete reviews |

Time standards are also set out in the caseload and constitution policy. |

Achieved |

12. Abide by the Australian Public Service (APS) Values and Code of Conduct (staff) |

New staff attend induction training, which includes training on the APS Values and the Code of Conduct. Ongoing staff complete refresher training at regular intervals. |

Achieved |

13. Abide by the Member Code of Conduct (members) |

All new members attend induction training, which includes the Member Code of Conduct. All members complete annual conflict of interest declaration forms and undergo performance reviews by senior members. |

Achieved |

14. Publish information on caseload and tribunal performance |

Information relating to the tribunals' caseload and performance in the current and previous financial years is published on the tribunals' website (under 'statistics'). Further statistics, including those on the judicial review of tribunal decisions, are available in all tribunal annual reports. |

Achieved |

The tribunals are particularly conscious that a high proportion of clients have a language other than English as their first language. Clear language in letters and forms, and the availability of staff to assist applicants are important to ensuring that applicants understand their rights, and our procedures and processes.

The tribunals' website is a significant information resource for applicants and others interested in the work of the tribunals. The publications and forms available on the website are regularly reviewed to ensure that information and advice are up-to-date and readily understood by clients.

The service charter (including translations in 10 community languages) is available on the website, along with the tribunals' plan, the Member Code of Conduct, the Interpreters' Handbook and Principal Member directions relating to the conduct of reviews. The 'Information for Representatives' webpage is aimed specifically at supporting representatives, bringing together the most often used resources and information. A 'Frequently Asked Questions' page answers representatives' most commonly asked questions.

The tribunals have offices in Sydney and Melbourne which are open between 8.30am and 5.00pm on working days. The tribunals have an arrangement with the AAT for counter services and hearings at AAT offices in Brisbane, Adelaide and Perth. The tribunals also have a national enquiry number (1300 361 969) available from anywhere in Australia (calls are charged at the cost of a local call, more from mobile telephones). Persons who need the assistance of an interpreter can contact the Translating and Interpreting Service (TIS) on 131 450 for the cost of a local call.

The tribunals' have a Reconciliation Action Plan, which was published in April 2011, and a Workplace Diversity Program. Further information about these strategies and plans is set out in part 4.

Complaints

As outlined above, the tribunals' service charter sets out the standards of service that clients can expect. It also sets out how clients can comment on or complain about the services provided by the tribunals. The service charter is available on the 'complaints and compliments' page on the tribunals' website.

A person who is dissatisfied with how the tribunals have dealt with a matter or with the standard of service they have received, and who has not been able to resolve this by contacting the office or the officer dealing with their case, can forward a written complaint marked 'confidential' to the Complaints Officer. A complaints and compliments button on the homepage of the tribunals' website makes it easier for clients to make a complaint.

Alternatively, a person can make a complaint to the Commonwealth Ombudsman, although, as a general rule, the Ombudsman will not investigate complaints until they have been raised with the relevant agency.

The tribunals will acknowledge receipt of a complaint within five working days. A senior officer will investigate the complaint and aim to provide a written response to the complaint within 20 working days of receipt of the complaint. With the exception of five matters, all complaints dealt with in 2011–12 were responded to within 20 working days.

Table 3.4 sets out the number of complaints finalised over the last three years.

Table 3.4 – Complaints finalised

2011–12 |

2010–11 |

2009–10 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| MRT | |||

Complaints resolved |

10 |

13 |

18 |

Cases decided |

8,011 |

6,577 |

7,580 |

Complaints per 1,000 cases |

1.2 |

2 |

2.4 |

| RRT | |||

Complaints resolved |

8 |

8 |

4 |

Cases decided |

2,804 |

2,604 |

2,157 |

Complaints per 1,000 cases |

2.8 |

3.1 |

1.9 |

The majority of complaints related to the conduct of the review process. Others were about the timeliness of the review or the decision, and one complaint was in relation to staff conduct. Following investigation, the tribunals formed the view that two of the complaints made during the year related to matters that could have been handled more appropriately.

Two examples of complaints received in 2011–12 are provided below.

Case 1 – Concerns were raised with the MRT that the applicant was not given adequate time to obtain evidence following a hearing and that the presiding member undertook to provide a further hearing if an unfavourable decision was likely to be made on the material before it. The tribunal wrote to the complainant indicating that the presiding member would offer another opportunity to appear before the tribunal to give evidence and present arguments if a favourable decision could not be made on the material before the tribunal.

Case 2 – Concerns were raised with the MRT that tribunal staff did not make adequate effort to notify an applicant of their hearing date. The tribunal wrote to the complainant indicating that notification of the hearing was faxed to the applicant's representative. Confirmation of successful fax transmission was provided to the complainant. It was also noted that the fax number was the same one to which the tribunal successfully had sent correspondence on previous occasions.

Table 3.5 sets out the complaints made to the Commonwealth Ombudsman over the last three years and the outcomes of the complaints resolved.

Table 3.5 – Complaints to the Commonwealth Ombudsman

2011–12 |

2010–11 |

2009–10 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

New complaints |

1 |

26 |

19 |

Complaints resolved |

1 |

24 |

18 |

Administrative deficiency found |

0 |

0 |

0 |

Migration agents

More than 64% of applicants were represented in 2011–12. With limited exceptions, a person acting as a representative is required to be a registered migration agent. Registered migration agents are required to conduct themselves in accordance with a code of conduct. The tribunals referred four matters to the Office of the Migration Agents Registration Authority (OMARA) during 2011–12 relating to the conduct of migration agents. OMARA is responsible for the registration of migration agents, monitoring the conduct of registered migration agents, investigating complaints and taking disciplinary action against registered migration agents who breach the code of conduct or behave in an unprofessional or unethical way.

Community and interagency liaison

The tribunals established a Stakeholder Engagement Committee in November 2011, to oversee engagement and communication with external stakeholders. The committee's immediate priority was to develop a new plan for engaging with the tribunals' range of stakeholders.

The tribunals' Stakeholder Engagement Plan 2012–14 was finalised in June 2012, and outlines the principles for engaging with clients and stakeholders, and strategies to support and improve communication and services.

The tribunals hold twice-yearly community liaison meetings in Melbourne, Sydney, Brisbane, Adelaide and Perth to exchange information with key stakeholders. The meetings are attended by representatives of migration and refugee advocacy groups, legal and migration agent associations, human rights bodies, the department and other government agencies. Fifty-one representatives attended meetings in November 2011, and following the invitation of several new organisations on the recommendation of the committee, there were 75 attendees at the April and May 2012 meetings. At community liaison meetings the tribunals provide an update on legislative and corporate developments, and attendees can raise matters that arise out of their dealings with the tribunals. Monthly email updates are also sent out to community liaison members, which contain information about caseloads and recent developments. Meeting minutes and email updates are published on the tribunals' website.

The tribunals held 'open days' or public information sessions in 2012. MRT information sessions were held in Melbourne, Brisbane and Sydney during Law Week in May 2012, and the RRT held information sessions in Adelaide, Melbourne and Sydney during Refugee Week in June 2012. Information sessions involve staged hearings and presentations from tribunal members and staff on processes and caseloads. This is the first time the tribunals have held MRT information sessions, and the first time information sessions have been held in Brisbane and Adelaide. There was a strong turnout and positive feedback from those who attended. These events provide an opportunity to enhance access for the wider community and promote a greater understanding of tribunal operations. Information sessions will continue to be held in future years.

Members and senior officers of the tribunals have continued to be active participants in several bodies, including the national and state chapters of the Council of Australasian Tribunals, the Australasian Institute of Judicial Administration (AIJA), the Australian Institute of Administrative Law and the International Association of Refugee Law Judges (IARLJ). In September 2011, the Principal Member, Deputy Principal Member and several members attended the ninth annual IARLJ World Conference in Bled, Slovenia. The conference Between Border Control, Security Concerns and International Protection: A Judicial Perspective included a range of international speakers reflecting on issues affecting refugee case processing and decision making.

Members presented on the work of the tribunals at several events in 2011–12. In March 2012, the Principal Member gave a speech to the Law Council of Australia CPD Immigration Law Conference in Sydney about the new complementary protection criterion and the Deputy Principal Member presented on the use of technology in merits review. In April 2012, the Deputy Principal Member presented to the University of New South Wales Forced Migration and Human Rights in International Law unit on refugee status determination. The Deputy Principal Member presented at the Migration Alliance's Annual Conference in June 2012 on effectively representing clients before the MRT. In March 2012, the tribunals started publishing speeches and presentations given by members and staff on its website.

The tribunals hold regular meetings with the department, the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade and the AAT. Memoranda of understanding between the tribunals and these organisations reflect the statutory and operational relationships between the agencies.

Member Mr Charlie Powles presides over a staged hearing at the Melbourne RRT information session during 2012 Refugee Week.

Major reviews

In December 2011, the Minister commissioned Professor the Hon Michael Lavarch, AO, to undertake a review of the increased workload of the tribunals. The review examined the increase in lodgements to both tribunals, including anticipated lodgements from irregular maritime arrivals.

The Report on the increased workload of the MRT and the RRT, published in June 2012, noted significant increases in case lodgements for the tribunals which have led to a large backlog of cases, particularly in matters before the MRT. The report noted that the demand for the tribunals' services had increased significantly and that the tribunals' resources primarily and, to a lesser extent, its practices, had not matched the increased demand.

The report made 18 recommendations including:

- Developing joint department-tribunal strategies and using short-term member appointments to reduce the MRT backlog by 50% by 1 July 2014;

- Case management efficiencies through greater member specialisation and trialling hearing-based case allocations;

- Providing national and end-to-end case support to members, instituting flexible working arrangements and stronger senior member leadership;

- Legislative change to amend the procedural code, appoint a second Deputy Principal Member and remit suitable cases to the department for reconsideration; and

- Transferring all IPAO cases to the RRT as soon as possible.

The Minister released the report on 29 June 2012 and supported the recommendations. The tribunals and department are working together on implementation.

Significant changes in the nature of functions or services

Complementary protection

On 24 March 2012, amendments to the Migration Act and Migration Regulations introducing a complementary protection criterion took effect. The amendments apply to all new protection visa applications made on or after the commencement date, and to all protection visa applications which had not been finally determined before the commencement date, including all undecided applications with the RRT.

The effect of the amendments is that where an applicant does not meet the definition of a refugee under the Refugees Convention, a protection visa may be granted if there are substantial grounds for believing that there is a real risk the applicant will suffer significant harm if returned to another country.

Single protection visa process

In November 2011, the government announced that a single protection visa process would apply to both boat and air arrivals. The effect of the change from 24 March 2012 is that the Minister has been exercising his discretion to permit irregular maritime arrivals to apply for protection visas. Those who are not permitted to apply for a protection visa, including irregular maritime arrivals who had a primary interview before 24 March 2012, continued to be processed through non-statutory processes.

Developments since the end of the year

In June 2012, the Minister announced that from 1 July 2012 the administration of IPAO functions will transfer from the department to the tribunals, and the tribunals will be responsible for administering the finalisation of the IPAO caseload. The transition of functions and staff was effected through machinery-of-government arrangements.

Case studies

Matters before the tribunals

The following case studies provide an insight into the range of matters which come before the tribunals.

MRT tourist – genuine visit – set aside

The visa applicant was a 75 year old Sri Lankan national who was sponsored by his son in Australia. The visa applicant claimed that he and his spouse had visited their daughter in Canada for two years where they pursued permanent residence, before opting to return to live in Sri Lanka due to its warmer climate. He claimed that they had also lived in the United States for 12 months with another daughter. The visa applicant claimed that he was a retired ex-serviceman who was entitled to receive free medical benefits, and that his wife had an older brother who lived in hostel care in Sri Lanka and required her assistance. He also claimed that he had another son in Sri Lanka who had a wife and three children, one of whom had Down syndrome, and that he and his wife assisted with child minding where necessary. The visa applicant claimed that due to his age, this may be his last opportunity to visit his family in Australia and that he wanted to be present at his grandson's birthday as well as experience a Christmas in Australia. He further claimed that his wife had visited Australia in 1989 and 1995, complying with her visa requirements on both occasions.

The tribunal noted that the visa applicant had family ties in Sri Lanka, and accepted that the visa applicant and his spouse played an important role in relation to their disabled grandson in Sri Lanka. The tribunal also noted that the visa applicant's wife did not overstay either of her previous visas. The tribunal accepted that the review applicant had undertaken to provide the visa applicant with accommodation and financial support during his proposed visit to Australia, and that he had the financial capacity to do so. Accordingly, the tribunal was satisfied that the expressed intention of the visa applicant only to visit Australia was genuine.

MRT student cancellation – set aside

The applicant's student visa was cancelled after the University of Wollongong (UOW) certified him as not achieving satisfactory course progress. In May 2011, the Federal Magistrates Court (FMC), by consent, set the MRT decision affirming the primary decision aside and remitted the matter to the tribunal. The FMC's orders included a note that the “tribunal erred in finding that the fact that the student was not an accepted student at that time did not operate to invalidate the certificate that Wollongong University issued for the purposes of condition 8202(3).”

Whilst the second tribunal entertained doubts as to the status of the note as part of the orders, it found that His Honour's reasons made it clear that the previous tribunal had erred. Accordingly, the tribunal found that it must give effect to the FMC's note, meaning that if the tribunal found that, at the time of certification by UOW, the applicant was not “an accepted student”, it must further find that the certificate issued by UOW was invalid. The tribunal found that the applicant was not an accepted student at time of certification because his enrolment had ceased from November 2008, and that the certificate was invalid. As a consequence, the tribunal found that the visa cancellation decision must be set aside. The tribunal noted that there were arguments in favour of the view that the validity of a certification given by an education provider did not require the student to be an accepted student of the provider at the time the certification was given.

MRT skilled – suitable skills assessment – affirmed

The visa applicant was a national of Iraq who had nominated the occupation of an 'Electrical Supervisor' in his application of 2008. The applicant provided evidence that Trades Recognition Australia (TRA) had assessed his skills for the occupation of 'Electrician (General)'. He claimed that as of 2009, TRA no longer conducted assessments for the occupation of 'Electrical Supervisor', as the Australian Standard Classification of Occupations (ASCO) classification had been superseded by Australian and New Zealand Standard Classification of Occupations (ANZSCO), and the only assessment available was for the occupation of a General Electrician. The applicant claimed that he had contacted the department, who told him that they had no difficulty converting from one occupation to the other, and TRA had also informed him that they could not assess him against the old provisions. The applicant claimed that he was a victim of the changing of the regulations, and he referred to the information contained on the department's website concerning the two occupations. He claimed that he was supported by his employer, and that he had the skills and qualifications of a supervisor. The applicant claimed that at the time of lodgement he was given wrong information by the department as he was advised that he did not have to apply for a skills assessment at that time.

The tribunal accepted that the applicant could no longer obtain a skills assessment against the occupation of 'Electrical Supervisor', noting that it considered it preferable if TRA was able to conduct assessments against ASCO occupations for those applicants who made their migration applications before ANZSCO came into effect. Nevertheless, these difficulties did not allow, in the tribunal's view, for a different application of the relevant legislative requirement, noting that clause 176.212 required an applicant's skills to be assessed against the nominated occupation. The tribunal therefore found that the skills assessment that the applicant had presented was not for his nominated occupation, but for a different occupation. The tribunal did not accept the applicant's assertion that the two occupations were the same, noting that the ANZSCO specified that the occupation of 'Electrician (General)' only partially matched the occupation of 'Electrical Supervisor'. Further advice received by the tribunal from TRA indicated that there was no partial match because the ANZSCO listing for 'Electrician (General)' did not incorporate supervisor duties, and it considered this advice to be persuasive. The tribunal further noted that if the applicant had applied for his skills assessment at the time when he made the application, as he was required to do by clause 176.212, it would have been unlikely that he would have been affected by any subsequent changes to the legislation or the TRA's assessment procedures. The tribunal affirmed the decision not to grant the applicant a visa.

MRT remaining relative – affirmed

The applicant, who was originally from South Africa, entered Australia in July 2004, and he had also spent a number of periods in Australia prior to this time. In June 2008, he applied for a visa on the basis that he was the remaining relative of his mother. He claimed that his parents had divorced, and that his father had since remarried and had two more children and was now living in Namibia. The applicant claimed that his mother had also remarried, and that the family decided to migrate to Queensland with the applicant and his two biological siblings. The applicant claimed that he had had no relationship with his biological father since he left school, and that due to this estrangement he had no contact with his father's second family. The applicant's biological brother and sister claimed that they also remained estranged from their father. The applicant claimed that Australian law stated that people who went missing for a long time were legally assumed to be dead, and that his father was considered dead by the applicant. The applicant's biological brother claimed that the applicant had ties to Australia, referring to the applicant's relationship with his children, and his mother claimed that the applicant was a hard worker on their farm and that he was popular with his co-workers and people in their community. She further claimed that the applicant was needed on the farm, and she held concerns about him returning to South Africa, especially as a white farmer.

The tribunal found that the applicant's father was a near relative of the applicant, in spite of the fact that the applicant's father and mother were now divorced. It found that while there was a lack of contact between the applicant and his biological father, there was nothing to support a conclusion that his father was no longer living. The tribunal further found that the applicant's mother had remarried and that his stepfather's two children from a previous marriage were the visa applicant's step-brother and step-sister respectively. The tribunal was not satisfied that the applicant met regulation 1.15(1)(c) of the definition of remaining relative. The tribunal accepted that the applicant had not had any contact with his father for many years, and it further noted that the applicant had been in Australia since 2004, with evidence indicating that his mother, brother and sister were all Australian citizens. The tribunal accepted the evidence which indicated that the applicant had engaged in a range of activities in Australia and that he was well regarded and valued by many in his community. Having regard to the applicant's circumstances and the ministerial guidelines relating to the Minister's discretionary powers, the tribunal considered that this case should be referred to the department to be brought to the Minister's attention.

MRT partner – genuine relationship – set aside

The Australian sponsor was a 56 year old man who was living in Singapore, and whose initial application had been refused as the delegate was not satisfied that the couple were in a genuine and committed relationship to the exclusion of all others. The review applicant claimed that he had met his partner whilst working in Singapore in 2008, and that over the following two weeks a relationship had developed, with the visa applicant staying with him in his apartment. Over the next twelve months, the applicants claimed that they lived together in Singapore. The review applicant claimed that the visa applicant was forced to return to Vietnam due to the expiry of her visa, and that he travelled to Vietnam on a number of occasions to visit her. He claimed that on cessation of his employment in November 2009 he returned to Australia, and the visa applicant was subsequently granted a visitor visa, staying with the review applicant for periods in 2010 and 2011. The review applicant submitted that he had moved to Hanoi in September 2011 to live with the visa applicant, and that they planned to move to Australia. The review applicant provided various supporting documentation, including a number of photos of the applicants together in social situations, evidence of money transfers amounting to approximately $80,000 to the visa applicant over the previous three years, and copies of letters from friends and the review applicant's children attesting to the genuineness of the relationship.

The tribunal found that the couple had shared their financial resources during the periods that they lived in Singapore, Australia and Vietnam, and it further noted that the review applicant had provided substantial financial support by transferring funds to the visa applicant's account in Vietnam on a monthly basis. The tribunal accepted that the applicants were jointly renting property in Hanoi, and it was satisfied that they had shared a household for a period of more than eighteen months. The tribunal was satisfied that the relationship was accepted by family and friends at both the time of application and the time of decision, noting that the applicants had given consistent evidence at the hearing that both families accepted and supported their relationship. The tribunal also gave weight to the fact that the review applicant had left his job in Australia and moved to Vietnam in order to be with the visa applicant, and that the visa applicant was willing to migrate to Australia and leave her family behind so that the review applicant could be closer to his children. The tribunal therefore found that the visa applicant met the requirements for the grant of a visa.

RRT El Salvador – complementary protection – set aside

The applicant claimed that she left El Salvador as she had been subject to death threats by members of the '18th street gang'. She claimed that someone who identified themselves as a member of the gang had phoned her home, demanding that US$2,000 be handed over within two hours or the applicant would be killed. She claimed that the caller had been able to provide a number of her personal details. The applicant claimed that the police advised that the threats should be taken seriously, so she moved to the home of relatives for six months until her sister was able to organise for her to come to Australia. She claimed that gang members had continued to enquire with her former neighbours as to her whereabouts. The applicant claimed that she later returned to El Salvador for six weeks as her elderly mother was seriously ill, and that during this time her brother received extortion demands for a sum of US$1,000, along with threats that if the money was not paid his children would be harmed. She claimed that the police advised that there was nothing further they could do, and that her brother subsequently negotiated to pay the gang a monthly sum, which he was still paying. The applicant claimed that neighbours were often connected to gang members, which meant that they could easily learn if she had returned.

The tribunal accepted that the applicant was a victim of extortion and death threats, noting that gang violence was widespread and had been carried out with virtual impunity for several years. The tribunal accepted the applicant's evidence that gang members would come to know of her return, and that there was a real chance that she could again become exposed to these threats, noting that her brother continued to be a victim. The tribunal noted the applicant's employment in low-paid work in Australia, and that she would not be in a position to meet any extortion demands. As such, the tribunal found that a failure to pay the money could result in a real chance of physical harm to the applicant; however, it found that the harm feared did not relate to any grounds specified in the Refugees Convention, as violent crime perpetrated by street gangs appeared to be undertaken at random. The tribunal then considered whether the applicant met the complementary protection criterion, and it found that the harm the applicant feared satisfied the definition of 'significant harm'. The tribunal noted that it had to determine whether there were substantial grounds for believing that there was a 'real risk' that she would suffer the significant harm, and it was satisfied that there existed a personal and direct risk to the applicant. Whilst the tribunal noted that there were a number of areas where gangs did not appear to be prevalent, it found that relocation was not a reasonable option due to the limited welfare safety net in El Salvador, and the fact that the applicant was a single female with no known family members living outside San Salvador. The tribunal was therefore satisfied that there was a real risk that she would suffer significant harm, and whilst it found that the applicant was not a refugee, the tribunal found that the applicant met the complementary protection criterion for the grant of a visa.

RRT China – anti-government – Jasmine Movement – affirmed